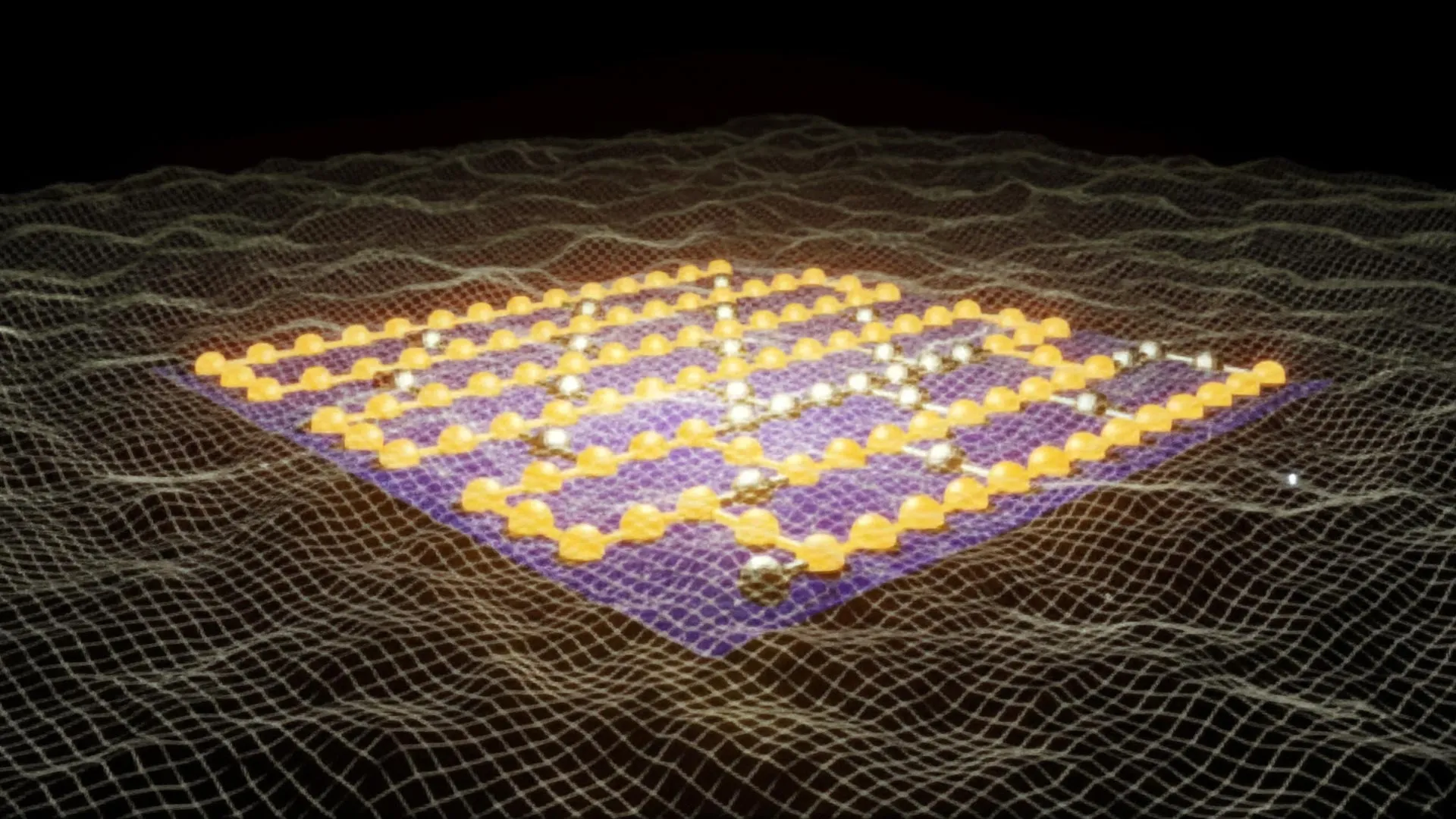

The team, led by physicists Jon Simon and Adam Shaw, has developed a novel optical cavity architecture that effectively acts as a highly efficient "light trap" for the photons emitted by single atom qubits. These atoms, suspended within the cavities, store quantum information. Historically, a major hurdle has been the fact that atoms emit light in all directions and at relatively slow rates, making it difficult to capture this quantum information efficiently, especially when dealing with a large number of qubits. The Stanford team’s innovation lies in their ability to equip each atom with its own meticulously engineered optical cavity. This allows the emitted photons, which carry the quantum state of the qubit, to be precisely guided towards a detector. This advancement signifies a critical step towards building scalable quantum computers, with a prototype demonstrating over 500 cavities and a clear path to systems containing millions of qubits.

The research, published in the prestigious journal Nature, details a system comprising 40 optical cavities, each housing a single atom qubit. This was followed by a larger prototype showcasing more than 500 cavities, a testament to the scalability of their design. Professor Jon Simon, the study’s senior author, emphasized the urgency of rapid qubit readout for building functional quantum computers. "If we want to make a quantum computer, we need to be able to read information out of the quantum bits very quickly," he stated. "Until now, there hasn’t been a practical way to do that at scale because atoms just don’t emit light fast enough, and on top of that, they spew it out in all directions. An optical cavity can efficiently guide emitted light toward a particular direction, and now we’ve found a way to equip each atom in a quantum computer within its own individual cavity." This individualistic approach to light trapping ensures that information from each qubit can be collected with unprecedented speed and fidelity.

The principle behind an optical cavity involves trapping light between two or more highly reflective surfaces, causing it to bounce back and forth. This creates a resonant structure that can enhance the interaction between light and matter. While the concept of optical cavities has been explored for decades, their application to single atoms has been fraught with challenges due to the atom’s minuscule size and near-transparency, making strong light-matter interaction difficult to achieve. The Stanford team’s novel design overcomes this by integrating microlenses directly within each cavity. These microlenses precisely focus the light onto the single atom, significantly amplifying the interaction and enabling efficient extraction of quantum information even with fewer light reflections.

Adam Shaw, a Stanford Science Fellow and the first author of the study, elaborated on the transformative nature of their new cavity architecture. "We have developed a new type of cavity architecture; it’s not just two mirrors anymore," he explained. "We hope this will enable us to build dramatically faster, distributed quantum computers that can talk to each other with much faster data rates." This departure from traditional cavity designs opens up possibilities for highly interconnected quantum computing networks, where quantum processors can communicate and collaborate at speeds currently unimaginable.

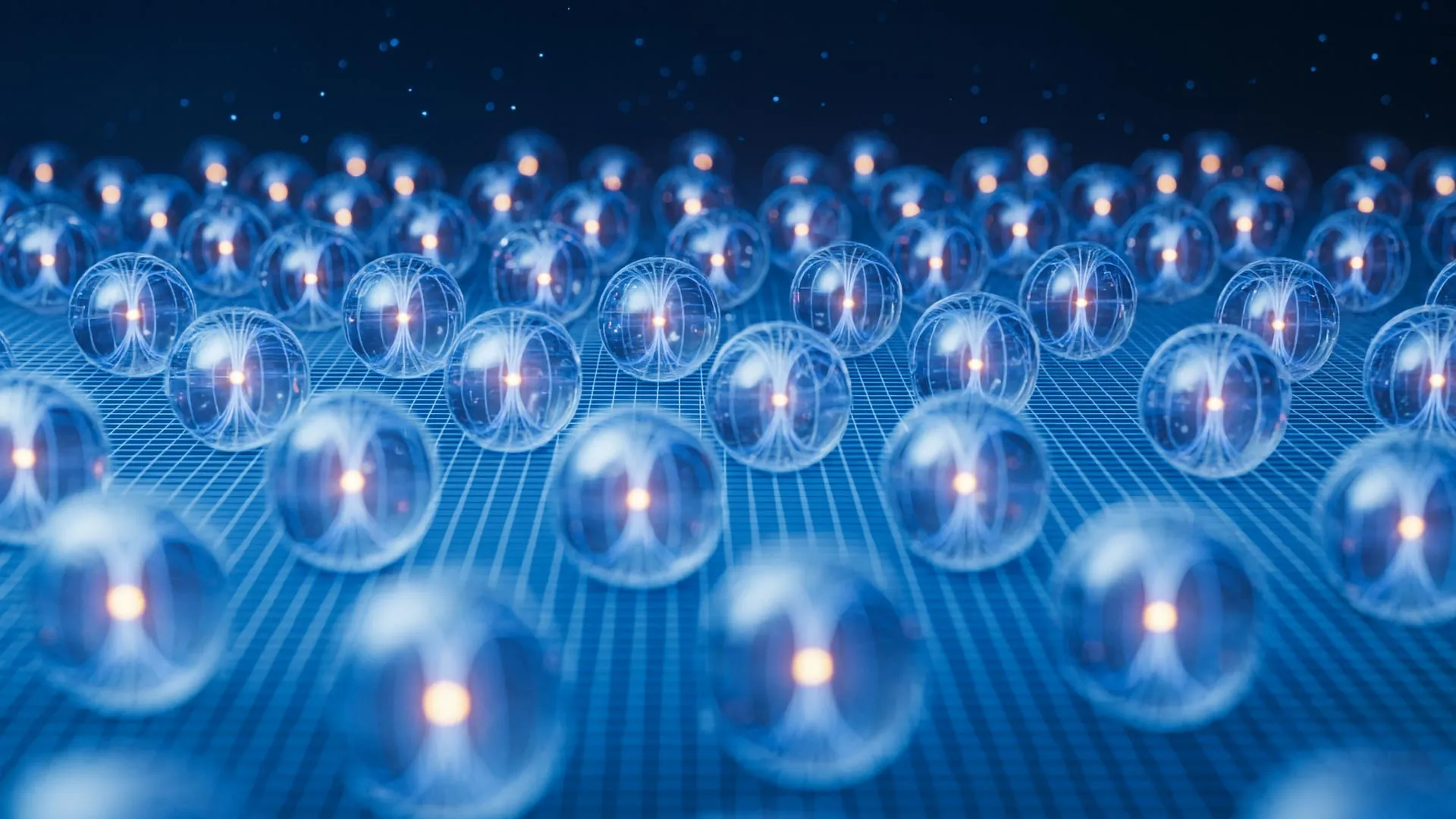

The fundamental advantage of quantum computing lies in its departure from the binary limitations of classical computing. Classical computers process information using bits, which can represent either a 0 or a 1. Quantum computers, on the other hand, utilize qubits, which leverage quantum mechanical phenomena like superposition. A qubit can represent 0, 1, or a combination of both simultaneously. This inherent parallelism allows quantum computers to explore a vast number of possibilities concurrently, making them exceptionally well-suited for certain types of calculations that are intractable for classical machines. Professor Simon drew an analogy to illustrate this difference: "A classical computer has to churn through possibilities one by one, looking for the correct answer. But a quantum computer acts like noise-canceling headphones that compare combinations of answers, amplifying the right ones while muffling the wrong ones."

The ultimate goal of quantum computing research is to achieve "quantum supremacy," where quantum computers can outperform the most powerful classical supercomputers. Scientists estimate that achieving this milestone will require quantum computers with millions of qubits. The Stanford team’s parallel light-based interface, demonstrated in their current study, provides a robust and efficient foundation for scaling up to these immense qubit counts. By connecting multiple quantum computers through these cavity-based network interfaces, the vision of quantum data centers and full-scale quantum supercomputers becomes increasingly plausible. Their immediate next step is to expand their working array from tens of thousands to tens of thousands of cavities, paving the way for truly transformative quantum machines.

The potential impact of large-scale quantum computers extends far beyond raw computational power. Breakthroughs are anticipated in diverse scientific and technological domains. In materials science and chemical synthesis, quantum computers could accelerate the discovery of new materials with unprecedented properties, leading to advancements in energy storage, catalysis, and more. The field of drug discovery and development stands to be revolutionized, with the ability to simulate molecular interactions with exquisite accuracy, leading to the design of more effective and targeted therapies. Furthermore, the ability of quantum computers to break current encryption algorithms poses a significant challenge to cybersecurity, necessitating the development of new, quantum-resistant cryptographic methods.

Beyond the realm of computing, the efficient collection of light demonstrated by the Stanford team has broader scientific and technological implications. Their cavity arrays could significantly enhance the capabilities of biosensing and microscopy, providing deeper insights into biological processes and supporting advancements in medical diagnostics and research. In astronomy, these quantum networks could enable the development of optical telescopes with vastly improved resolution, potentially allowing scientists to directly image exoplanets and search for signs of life beyond our solar system. As Adam Shaw aptly put it, "As we understand more about how to manipulate light at a single particle level, I think it will transform our ability to see the world."

The journey toward realizing the full potential of quantum computing is ongoing, with significant engineering hurdles yet to be overcome. However, the innovative optical cavity design developed by the Stanford team represents a monumental leap forward, offering a clear and practical path toward building the million-qubit quantum computers of the future. This research, supported by a consortium of national science foundations and defense agencies, not only promises to accelerate scientific discovery but also has the potential to redefine our technological landscape and our understanding of the universe. The team’s commitment to open innovation is further underscored by the fact that some of the researchers hold patents related to the demonstrated resonator geometry, while also serving as consultants to a quantum computing company, highlighting the rapid translation of fundamental research into practical applications. The collaborative efforts of institutions such as Stony Brook University, the University of Chicago, Harvard University, and Montana State University underscore the global nature of this scientific endeavor.