Quantum computers, heralded for their ability to perform calculations at speeds unfathomable to classical machines, are on the cusp of a transformative leap. However, the very ambition of these powerful devices – to interconnect and form vast, reliable quantum networks – has been hampered by a persistent hurdle: the challenge of transmitting quantum information over significant distances. Until recently, the practical limit for linking two quantum computers was a mere few kilometers through fiber optic cables. This seemingly modest constraint meant that even within a single metropolitan area, such as linking the University of Chicago’s South Side campus with a quantum device housed in the iconic Willis Tower, communication was an impossibility. The distance, though geographically small, was an insurmountable chasm for current quantum networking technology.

However, a groundbreaking new study, published on November 6 in the prestigious journal Nature Communications, authored by Assistant Professor Tian Zhong of the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME), has shattered this limitation. Zhong’s team has unveiled a revolutionary approach that suggests quantum connections can be extended to an astonishing 2,000 kilometers (approximately 1,243 miles). This dramatic advancement redefines the scope of quantum networking, transforming a local communication challenge into the potential for continental-scale connectivity. To illustrate the magnitude of this breakthrough, the UChicago quantum computer, once incapable of reaching the Willis Tower, could now theoretically establish a quantum link with a device situated as far away as Salt Lake City, Utah.

"For the first time, the technology for building a global-scale quantum internet is within reach," declared Zhong, a researcher whose pioneering work in this field has recently earned him the esteemed Sturge Prize. This recognition underscores the profound impact of his team’s findings on the trajectory of quantum technology.

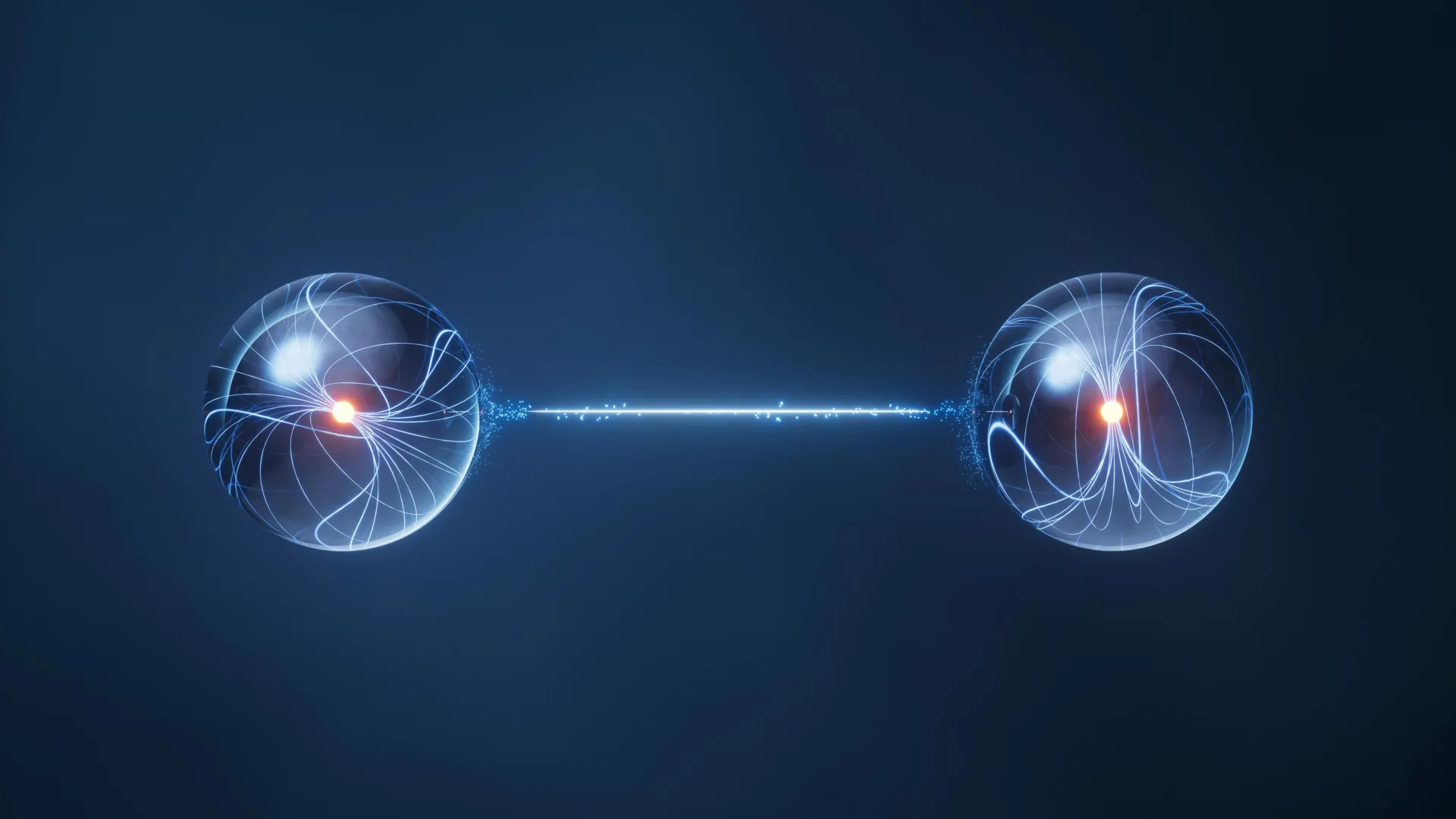

The cornerstone of this remarkable achievement lies in understanding and enhancing "quantum coherence." For high-performance quantum networks to function, researchers must first entangle atoms – a quantum phenomenon where two or more particles become inextricably linked, sharing the same fate regardless of the distance separating them. Crucially, this entanglement must be maintained as the quantum signals, encoded in these entangled states, traverse the fiber optic cables. The longer the "coherence time" of these entangled atoms – the duration for which their quantum state remains intact – the farther apart the connected quantum computers can effectively be.

In their seminal study, Zhong’s team achieved a monumental feat: they successfully extended the coherence time of individual erbium atoms from a mere 0.1 milliseconds to an impressive duration exceeding 10 milliseconds. In some of their most compelling experiments, they even recorded coherence times of 24 milliseconds. Under optimal conditions, this tenfold increase in coherence time translates directly into the capacity for quantum computers to communicate across distances of roughly 4,000 kilometers. This distance is comparable to the span between the UChicago PME campus and the city of Ocaña, Colombia, a testament to the truly global implications of their research.

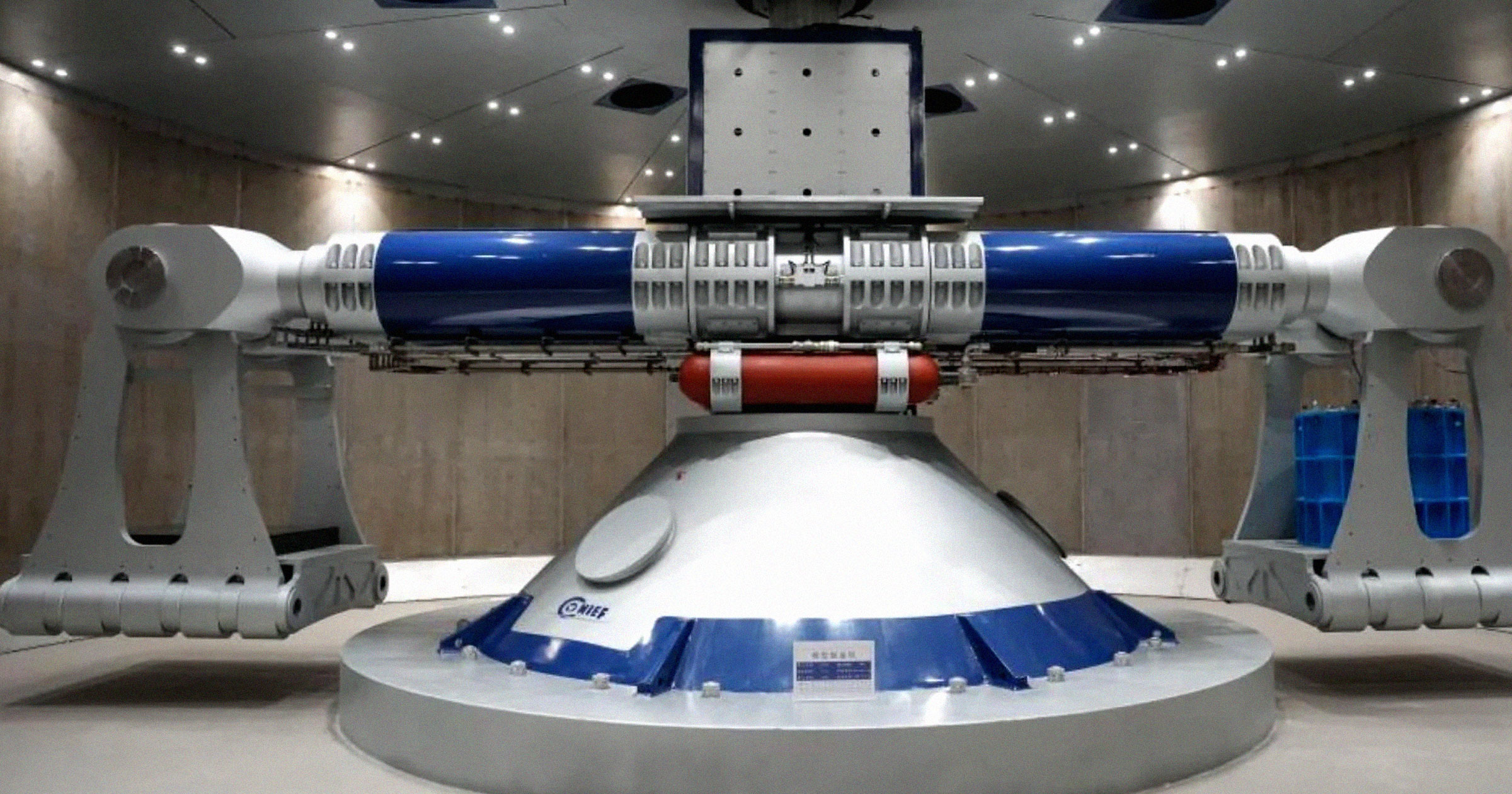

The ingenuity of Zhong’s team lies not in the discovery of exotic new materials, but in a radical reimagining of how existing materials are constructed. Instead of relying on novel substances, they focused on an innovative manufacturing process. The rare-earth doped crystals, essential for achieving quantum entanglement, were produced using a technique called molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE), a departure from the conventional Czochralski method.

Zhong aptly described the traditional Czochralski approach as akin to a "melting pot." He explained, "You throw in the right ratio of ingredients and then melt everything. It goes above 2,000 degrees Celsius and is slowly cooled down to form a material crystal." Following this high-temperature process, the solidified crystal must then be meticulously carved and shaped into usable components through chemical etching, a process Zhong likens to a sculptor chipping away at marble.

In stark contrast, MBE operates on a fundamentally different principle, resembling a form of atomic-scale 3D printing. This technique meticulously lays down the crystal structure in infinitesimally thin layers, precisely building the exact architecture required for the quantum device. "We start with nothing and then assemble this device atom by atom," Zhong elaborated. "The quality or purity of this material is so high that the quantum coherence properties of these atoms become superb." This atom-by-atom assembly process yields materials of unprecedented purity, directly leading to enhanced quantum coherence.

While MBE has found applications in other branches of materials science, its adaptation to this specific type of rare-earth doped material for quantum applications was a novel undertaking. For this pioneering project, Zhong collaborated closely with Shuolong Yang, an Assistant Professor specializing in materials synthesis at UChicago PME, to tailor the MBE process to their exacting requirements.

The significance of these findings has been recognized by leading figures in the field. Dr. Hugues de Riedmatten, a Professor at the Institute of Photonic Sciences and an expert in quantum optics who was not involved in the study, lauded the research as a "highly innovative" and "important step forward." He further commented, "It shows that a bottom-up, well-controlled nanofabrication approach can lead to the realization of single rare-earth ion qubits with excellent optical and spin coherence properties, leading to a long-lived spin photon interface with emission at telecom wavelength, all in a fiber-compatible device architecture. This is a significant advance that offers an interesting scalable avenue for the production of many networkable qubits in a controlled fashion." This external validation underscores the broad impact and potential of Zhong’s team’s work.

With the theoretical hurdles cleared and the material properties significantly enhanced, the next critical phase of the project involves rigorous real-world testing. The team is now focused on validating whether these improved coherence times can indeed support long-distance quantum communication outside the controlled environment of theoretical models and laboratory simulations.

"Before we actually deploy fiber from, let’s say, Chicago to New York, we’re going to test it just within my lab," Zhong stated, outlining their methodical approach to scaling up. Their immediate plan involves linking two quantum bits (qubits), each housed within separate dilution refrigerators – specialized cryogenic devices essential for maintaining quantum states – within Zhong’s laboratory. They will then connect these qubits using a substantial 1,000 kilometers of coiled fiber optic cable. This controlled, in-lab experiment will serve as a crucial verification step, ensuring that the system performs as predicted before embarking on more ambitious, larger-scale deployments.

"We’re now building the third fridge in my lab," Zhong revealed, offering a glimpse into the immediate future of their research. "When it’s all together, that will form a local network, and we will first do experiments locally in my lab to simulate what a future long-distance network will look like. This is all part of the grand goal of creating a true quantum internet, and we’re achieving one more milestone towards that." This incremental, yet profoundly impactful, approach signals a clear and determined path towards realizing the long-held dream of a global quantum internet, a network that promises to revolutionize computation, communication, and scientific discovery for generations to come.