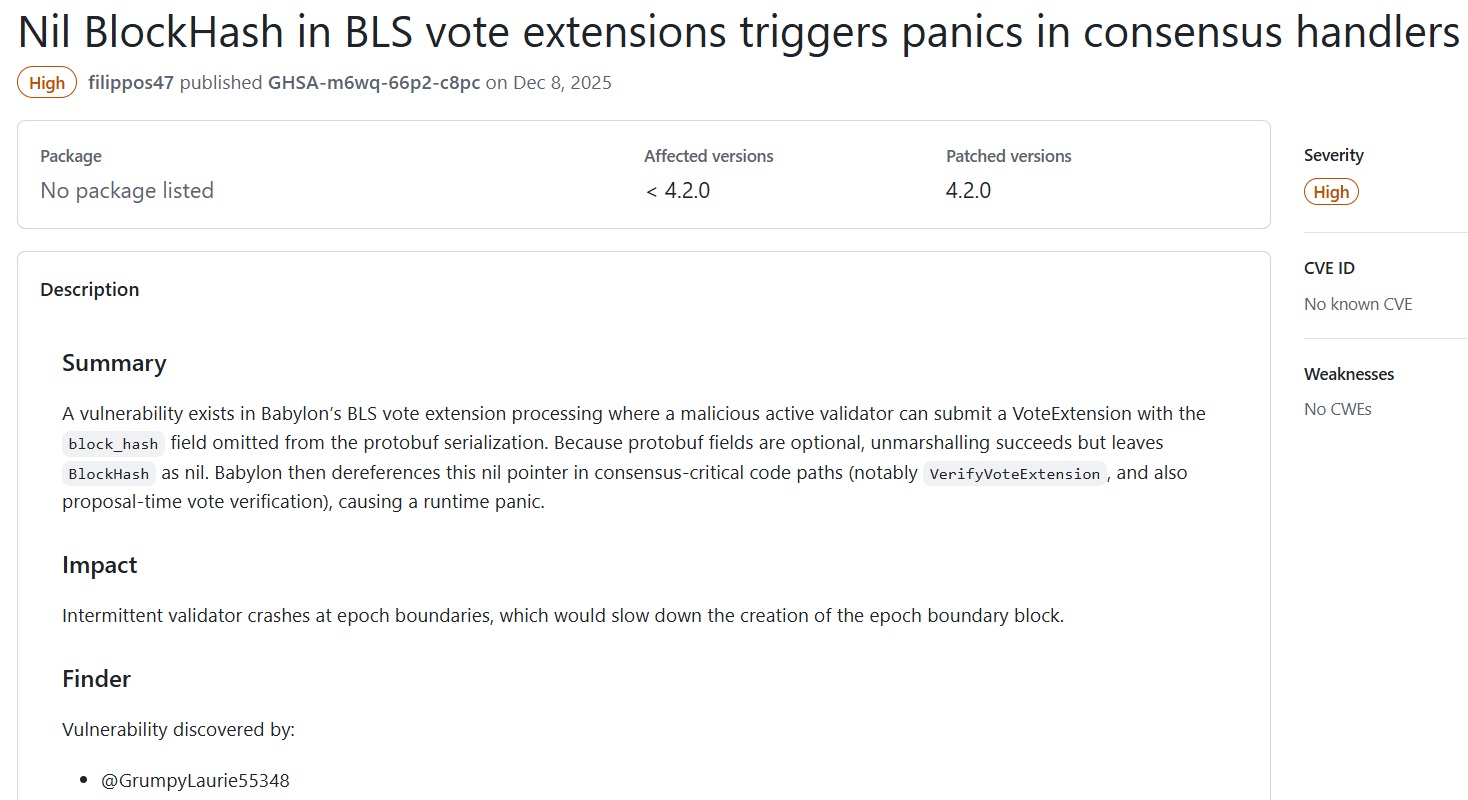

Quantum computers, renowned for their extraordinary computational prowess, have long been hampered by a fundamental limitation: the difficulty of connecting them over vast distances. This challenge has been a significant bottleneck in the development of large-scale, reliable quantum networks. Historically, the practical reach of quantum connections between two quantum computers was confined to a mere few kilometers via fiber optic cables. This meager span meant that even within the same metropolitan area, such as linking a quantum device on the University of Chicago’s South Side campus to one housed in the iconic Willis Tower, communication was an insurmountable hurdle due to the limitations of existing technology.

However, a groundbreaking new study, published on November 6th in the prestigious journal Nature Communications, offers a transformative solution. Led by Assistant Professor Tian Zhong of the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME), the research team has demonstrated a radical upgrade that could dramatically extend the range of quantum connections. Their findings suggest that, in theory, quantum links could span an astonishing distance of up to 2,000 kilometers (approximately 1,243 miles). To put this into perspective, a quantum computer at the University of Chicago could potentially communicate with a device situated as far away as Salt Lake City, Utah, a feat previously unimaginable.

Professor Zhong, a recent recipient of the distinguished Sturge Prize for his pioneering work in this field, expressed immense optimism about the implications of this breakthrough. "For the first time," he stated, "the technology for building a global-scale quantum internet is within reach." This sentiment underscores the profound impact this research could have on the future of computing and communication.

The Crucial Role of Quantum Coherence

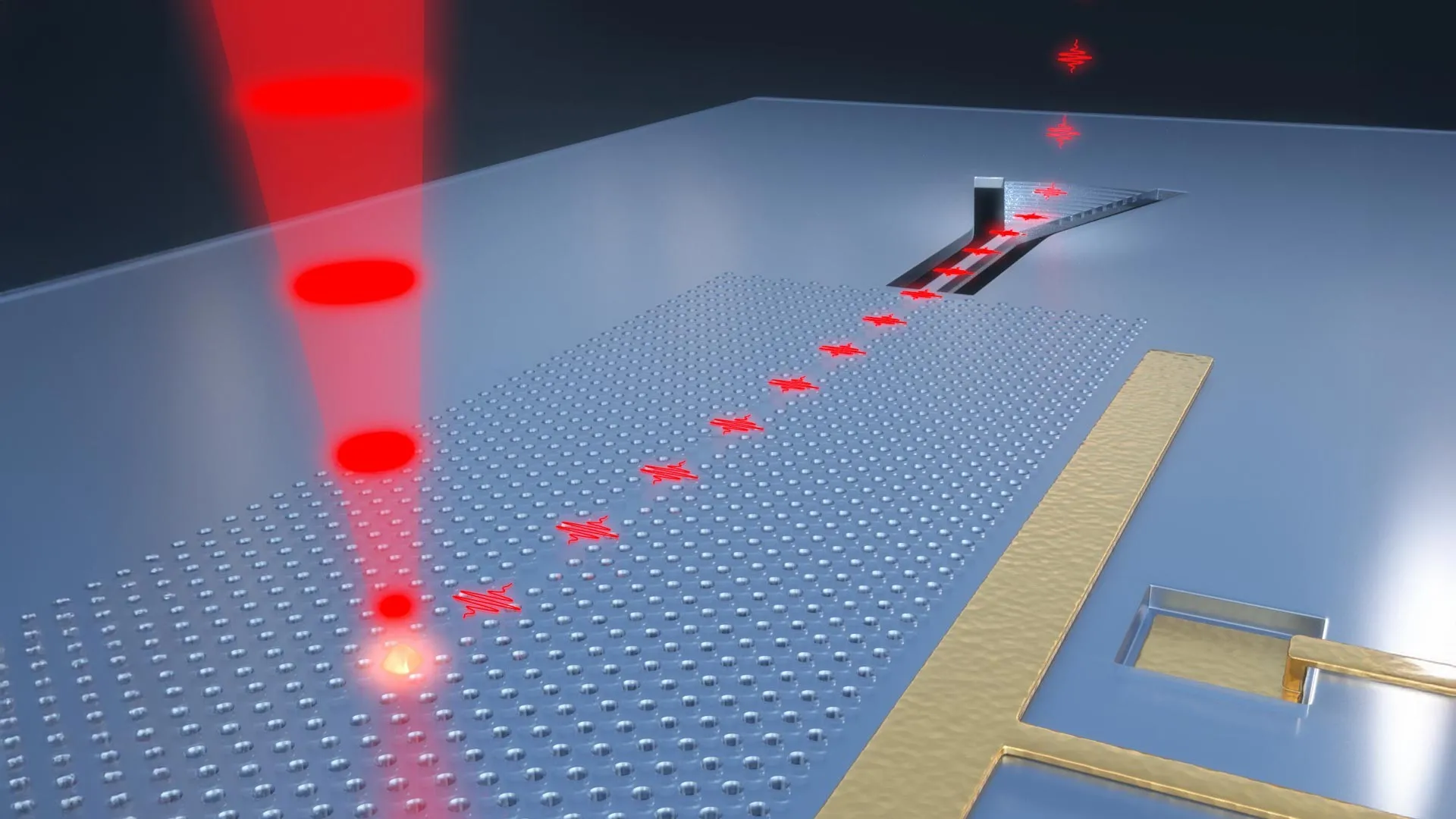

At the heart of building high-performance quantum networks lies the intricate process of entangling atoms and, critically, maintaining that entanglement as quantum signals traverse fiber optic cables. The longer the "coherence time" of these entangled atoms – essentially, the duration for which their quantum state remains intact – the greater the distance over which quantum computers can maintain a stable connection.

In their pivotal new study, Professor Zhong’s team achieved a remarkable feat by significantly enhancing the coherence time of individual erbium atoms. They successfully extended this coherence time from a mere 0.1 milliseconds to an impressive span exceeding 10 milliseconds. In one particularly successful experiment, they even recorded a coherence time of 24 milliseconds. Under ideal theoretical conditions, this substantial improvement could enable quantum computers to communicate across distances of approximately 4,000 kilometers. This distance is roughly equivalent to the span between the University of Chicago PME and Ocaña, Colombia, highlighting the truly global potential of their innovation.

Reimagining Material Construction for Quantum Advantage

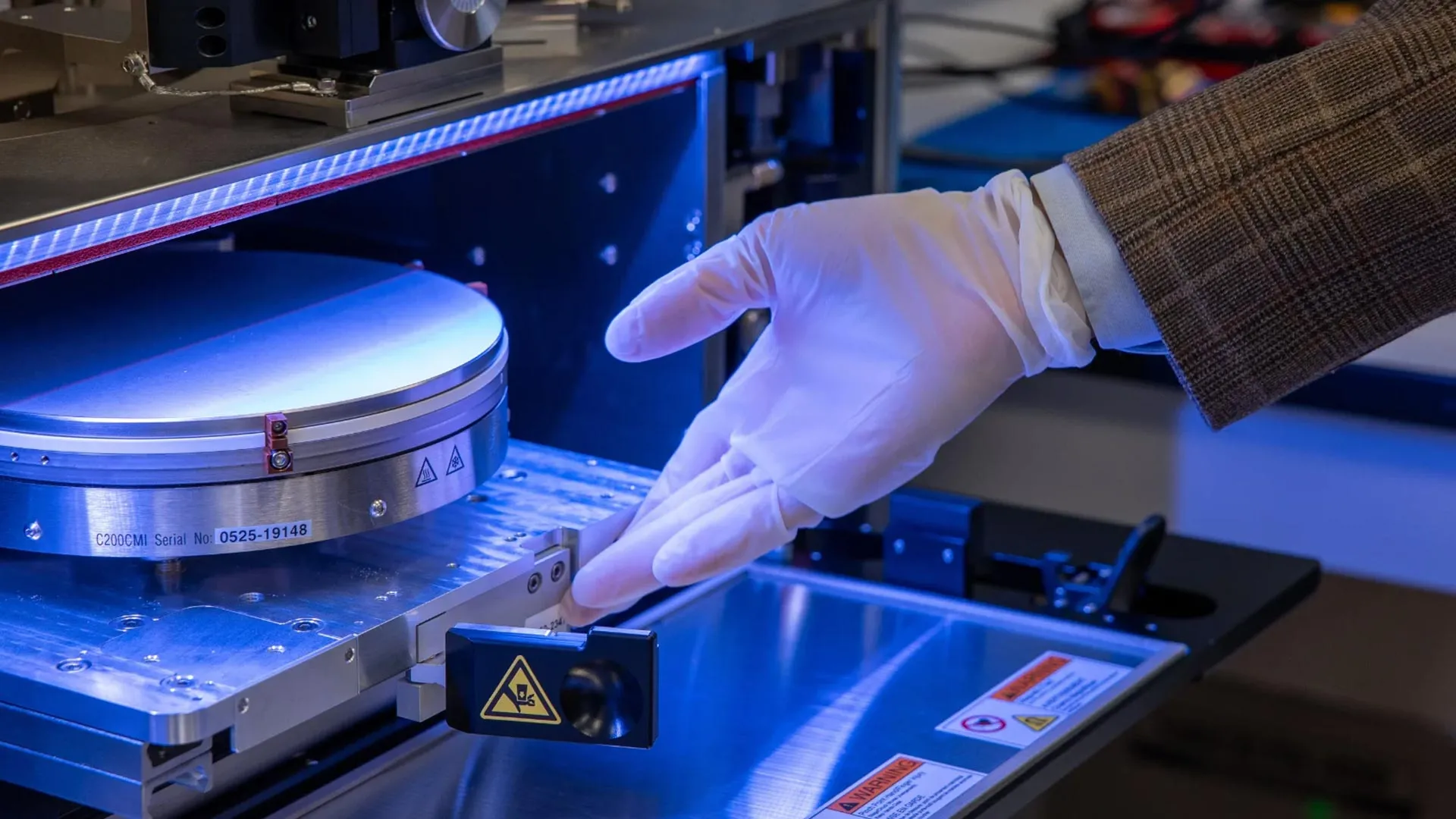

The revolutionary advancement did not stem from the discovery of exotic new materials. Instead, the UChicago team ingeniously re-envisioned the method by which crucial materials are constructed. For the rare-earth doped crystals essential for quantum entanglement, they eschewed the traditional Czochralski method in favor of molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE).

Professor Zhong vividly described the limitations of the conventional approach. "The traditional way of making this material is by essentially a melting pot," he explained, referring to the Czochralski method. "You throw in the right ratio of ingredients and then melt everything. It goes above 2,000 degrees Celsius and is slowly cooled down to form a material crystal." Following this high-temperature process, researchers would then chemically carve the cooled crystal into the desired component, a process Zhong likened to a sculptor painstakingly chipping away at marble.

MBE operates on an entirely different principle, one that Professor Zhong likened to "3D printing, but at the atomic scale." This sophisticated technique involves meticulously depositing the crystal in extremely thin layers, precisely building up the exact atomic structure required for optimal quantum device performance. "We start with nothing and then assemble this device atom by atom," Zhong emphasized. "The quality or purity of this material is so high that the quantum coherence properties of these atoms become superb."

While MBE has found applications in other branches of materials science, its adaptation to this specific type of rare-earth doped material was novel. To achieve this, Professor Zhong collaborated closely with Assistant Professor Shuolong Yang, a specialist in materials synthesis at UChicago PME, who played a crucial role in tailoring the MBE process for their quantum research needs.

The significance of this development was underscored by Professor Dr. Hugues de Riedmatten of the Institute of Photonic Sciences, who was not directly involved in the study but offered his expert opinion. He described the results as a "highly innovative" and "important step forward." Professor de Riedmatten elaborated, "It shows that a bottom-up, well-controlled nanofabrication approach can lead to the realization of single rare-earth ion qubits with excellent optical and spin coherence properties, leading to a long-lived spin photon interface with emission at telecom wavelength, all in a fiber-compatible device architecture. This is a significant advance that offers an interesting scalable avenue for the production of many networkable qubits in a controlled fashion." His assessment highlights the multifaceted advantages of the MBE approach, particularly its suitability for creating scalable and networkable quantum components.

Paving the Way for Real-World Quantum Network Tests

With this significant theoretical and material advancement achieved, the next critical phase of the project involves rigorously testing whether these enhanced coherence times can indeed support long-distance quantum communication in practical, real-world scenarios, moving beyond theoretical models.

Professor Zhong outlined their immediate plans. "Before we actually deploy fiber from, let’s say, Chicago to New York, we’re going to test it just within my lab," he explained. The team is meticulously preparing to link two qubits, each housed within separate, highly specialized dilution refrigerators (often referred to as "fridges") within Professor Zhong’s laboratory. This crucial test will involve utilizing 1,000 kilometers of coiled fiber optic cable to simulate the vast distances involved. This controlled experiment will allow them to meticulously verify that the system performs as predicted before venturing into larger-scale deployments.

"We’re now building the third fridge in my lab," Professor Zhong shared. "When it’s all together, that will form a local network, and we will first do experiments locally in my lab to simulate what a future long-distance network will look like." He concluded with a statement that encapsulates the ambitious trajectory of their research: "This is all part of the grand goal of creating a true quantum internet, and we’re achieving one more milestone towards that." This systematic, lab-based simulation is a vital step in de-risking the technology and building confidence for future, intercity, and ultimately, global quantum network infrastructure.