At the heart of this innovation lies the Penn team’s ingenious "Q-chip," a sophisticated piece of engineering designed to seamlessly orchestrate both quantum and classical data streams. Crucially, this chip "speaks the same language" as the modern web, a critical design choice that dramatically simplifies the integration of quantum technologies into existing networks. This compatibility is not merely a technical convenience; it represents a fundamental leap forward, potentially paving the way for a future quantum internet that could unlock unprecedented computational power and drive scientific discovery.

Quantum networks, at their core, rely on the enigmatic phenomenon of "quantum entanglement." This bizarre property links pairs of particles in such a profound way that measuring the state of one instantaneously influences the state of the other, regardless of the distance separating them. Harnessing this quantum entanglement holds immense promise for applications such as linking quantum computers to pool their formidable processing power. Such a interconnected quantum network could accelerate the development of advanced artificial intelligence, create more energy-efficient AI systems, and enable the design of novel drugs and materials that are currently beyond the reach of even the most powerful supercomputers.

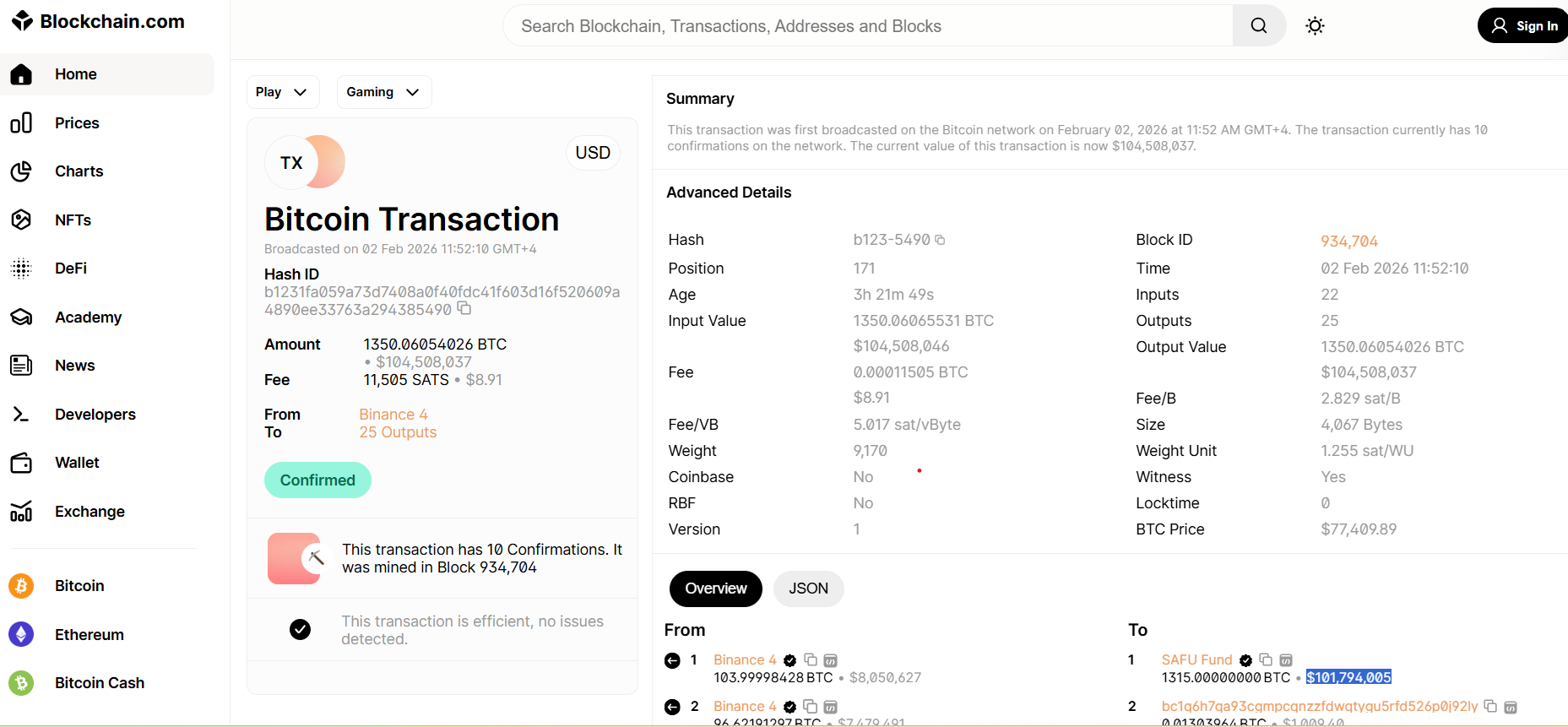

The significance of the Penn team’s work lies in its demonstration, for the first time on live commercial fiber, that a single chip can perform a multitude of essential functions. It can not only transmit quantum signals but also automatically compensate for noise, a pervasive challenge in quantum communication. Furthermore, it can efficiently bundle both quantum and classical data into standard internet-style packets, and critically, route these packets using the familiar addressing systems and management tools that govern our current online world. "By showing an integrated chip can manage quantum signals on a live commercial network like Verizon’s, and do so using the same protocols that run the classical internet, we’ve taken a key step toward larger-scale experiments and a practical quantum internet," remarks Liang Feng, Professor in Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) and in Electrical and Systems Engineering (ESE), and the senior author of the Science paper. This statement underscores the practical, real-world applicability of their research.

The Intrinsic Challenges of Scaling the Quantum Internet

The path towards a functional quantum internet is not without its formidable obstacles, primarily stemming from the inherent nature of quantum mechanics. Erwin Schrödinger, the renowned physicist who first coined the term "quantum entanglement," famously illustrated its perplexing nature with his thought experiment involving a cat in a box. In this scenario, the cat’s fate—alive or dead—remains uncertain until the box is opened. One interpretation suggests the cat exists in a superposition of both states simultaneously. This paradox offers a valuable analogy to the peculiar behavior of quantum particles. Once measured or observed, these particles lose their unique quantum properties, a phenomenon that presents a significant hurdle for scaling quantum networks.

"Normal networks measure data to guide it towards the ultimate destination," explains Robert Broberg, a doctoral student in ESE and a coauthor of the paper. "With purely quantum networks, you can’t do that, because measuring the particles destroys the quantum state." This fundamental limitation means that traditional methods of data routing, which rely on measurement and feedback, are incompatible with the delicate nature of quantum information.

Orchestrating the Delicate Dance of Classical and Quantum Signals

To circumvent this critical obstacle, the Penn team ingeniously developed the "Q-Chip," an acronym for "Quantum-Classical Hybrid Internet by Photonics." This novel chip is engineered to act as a sophisticated coordinator, managing the intricate interplay between "classical" signals, which are essentially standard streams of light, and the fragile quantum particles. "The classical signal travels just ahead of the quantum signal," clarifies Yichi Zhang, a doctoral student in MSE and the paper’s first author. "That allows us to measure the classical signal for routing, while leaving the quantum signal intact."

This ingenious approach can be visualized as a sophisticated railway system. The classical signal acts as the train’s engine, providing the necessary information for navigation, while the quantum information travels securely behind in "sealed containers." "The classical ‘header’ acts like the train’s engine, while the quantum information rides behind in sealed containers," elaborates Zhang. "You can’t open the containers without destroying what’s inside, but the engine ensures the whole train gets where it needs to go."

Because the classical header can be measured without compromising the quantum data, the entire system can adhere to the established Internet Protocol (IP) that governs today’s internet traffic. "By embedding quantum information in the familiar IP framework, we showed that a quantum internet could literally speak the same language as the classical one," states Zhang. "That compatibility is key to scaling using existing infrastructure." This linguistic parity is a cornerstone for future integration and expansion.

Adapting Quantum Technology to the Demands of the Real World

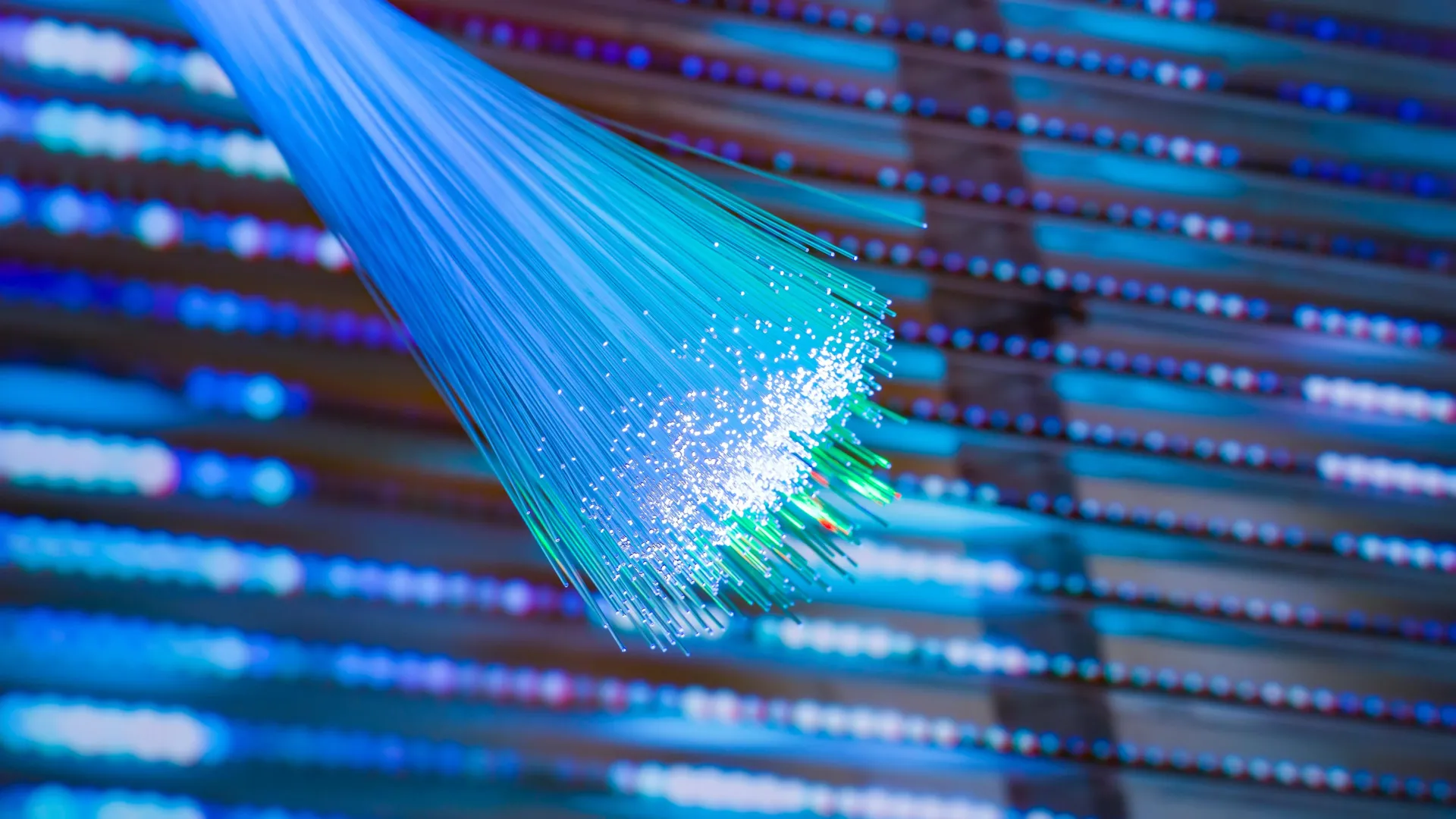

A significant hurdle in transmitting quantum particles over commercial infrastructure is the inherent variability and unpredictability of real-world transmission lines. Unlike the controlled environments of research laboratories, commercial networks are constantly subjected to fluctuations in temperature due to weather, vibrations from human activities such as construction and transportation, and even seismic activity. These external factors can easily disrupt and degrade the delicate quantum signals.

In response to these environmental challenges, the researchers engineered an advanced error-correction mechanism. This method leverages the correlation between the classical header and the quantum signal: interference affecting the classical signal is likely to impact the quantum signal in a similar manner. "Because we can measure the classical signal without damaging the quantum one," explains Feng, "we can infer what corrections need to be made to the quantum signal without ever measuring it, preserving the quantum state." This sophisticated feedback loop allows for real-time adjustments, maintaining the integrity of the quantum information.

In rigorous testing, the system consistently achieved transmission fidelities exceeding 97%. This impressive result demonstrates its robust ability to overcome the noise and instability that typically render quantum signals unusable outside of controlled laboratory settings. Furthermore, the Q-chip is fabricated from silicon using established manufacturing techniques, making it amenable to mass production. This scalability is crucial for the widespread adoption of the new approach. "Our network has just one server and one node, connecting two buildings, with about a kilometer of fiber-optic cable installed by Verizon between them," Feng notes. "But all you need to do to expand the network is fabricate more chips and connect them to Philadelphia’s existing fiber-optic cables." This suggests a modular and cost-effective expansion strategy.

Charting the Future Trajectory of the Quantum Internet

The primary impediment to extending quantum networks beyond metropolitan areas remains the current inability to amplify quantum signals without destroying their essential entanglement. While some research groups have successfully transmitted "quantum keys"—specialized codes for exceptionally secure communication—over long distances using ordinary fiber, these systems rely on a technique involving weak coherent light to generate random numbers. While highly effective for security applications, this method is not yet sufficient for linking actual quantum processors.

Overcoming this amplification challenge will necessitate the development of entirely new devices. However, the Penn study represents a crucial foundational step. It has unequivocally demonstrated that a single chip can effectively manage quantum signals over existing commercial fiber. This capability includes internet-style packet routing, dynamic switching for efficient data flow, and on-chip error mitigation, all operating in concert with the protocols that currently govern our vast digital networks.

"This feels like the early days of the classical internet in the 1990s, when universities first connected their networks," reflects Broberg. "That opened the door to transformations no one could have predicted. A quantum internet has the same potential." This sentiment captures the excitement and the immense, yet largely unwritten, future possibilities that this breakthrough portends.

This pioneering study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science, with vital support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation, the Olga and Alberico Pompa endowed professorship, and a PSC-CUNY award. Additional contributors to this groundbreaking research include Alan Zhu, Gushi Li, and Jonathan Smith from the University of Pennsylvania, and Li Ge from the City University of New York, whose collective efforts have propelled us closer to a quantum-connected future.