The advent of Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist drugs, notably popular medications like Wegovy and Ozempic, has undeniably revolutionized the landscape of weight management and metabolic health. Initially hailed as breakthrough treatments, these injectable medications have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in enabling patients to achieve significant weight reduction. Beyond their primary role in combating obesity, a growing body of research has revealed a constellation of other profound health benefits, positioning GLP-1s as a multi-faceted therapeutic marvel. They have been shown to lower the risk of cardiovascular disease, potentially stave off neurodegenerative conditions like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, and mitigate the progression of diabetic kidney disease. For many, these drugs have offered a lifeline, transforming health trajectories and improving quality of life in ways previously unimaginable.

However, as the widespread adoption of GLP-1s continues, a sobering reality is beginning to emerge, casting a significant shadow over their long-term use: the intense and often debilitating consequences that arise when patients discontinue these powerful medications. This grim wrinkle in the narrative raises a critical question for both patients and healthcare providers: are individuals embarking on a lifelong commitment to these often-expensive drugs, or is there a sustainable path to cessation without succumbing to severe repercussions?

A recent, comprehensive study spearheaded by researchers at the University of Oxford, published in the esteemed BMJ, has brought this challenge into sharp focus. This extensive review synthesized findings from 37 existing weight loss medication studies, encompassing over 9,000 participants, to provide a clearer picture of what happens post-cessation. The findings are stark: patients who stopped taking GLP-1 weight-loss medications experienced weight regain at a rate four times faster than those who relied solely on alternative behavioral programs, such as structured diets and increased physical activity. On average, participants reverted to their original weight a mere 1.7 years after discontinuing the medication.

The physiological and psychological impact of this rapid rebound is profound. Patients who have gone off the drugs describe an overwhelming return of hunger, a sensation far more intense and primal than they experienced before treatment. Tanya Hall, a patient who has navigated the on-again, off-again journey with GLP-1 injections, recounted her experience to the BBC, describing it as "like something opened up in my mind and said: ‘Eat everything, go on, you deserve it because you haven’t eaten anything for so long.’" This visceral urge, often described as a "terrible hunger," left her feeling "completely horrified" by the sheer volume of food she found herself consuming within days of stopping the medication. This isn’t merely a return to old habits; it’s an aggressive resurgence of appetite, driven by altered neurochemical pathways that GLP-1s had previously kept in check.

Worse still, the Oxford-led research team observed that the secondary health benefits, so lauded during active treatment, dissipated just as quickly as the weight loss. Critical health markers, including blood pressure and cholesterol levels, bounced back to their original, often unhealthy, levels within an average of 1.4 years. The study authors explicitly noted, "This review found that cessation of [weight management medications] is followed by rapid weight regain and reversal of beneficial effects on cardiometabolic markers. These findings suggest caution in short-term use of these drugs without a more comprehensive approach to weight management."

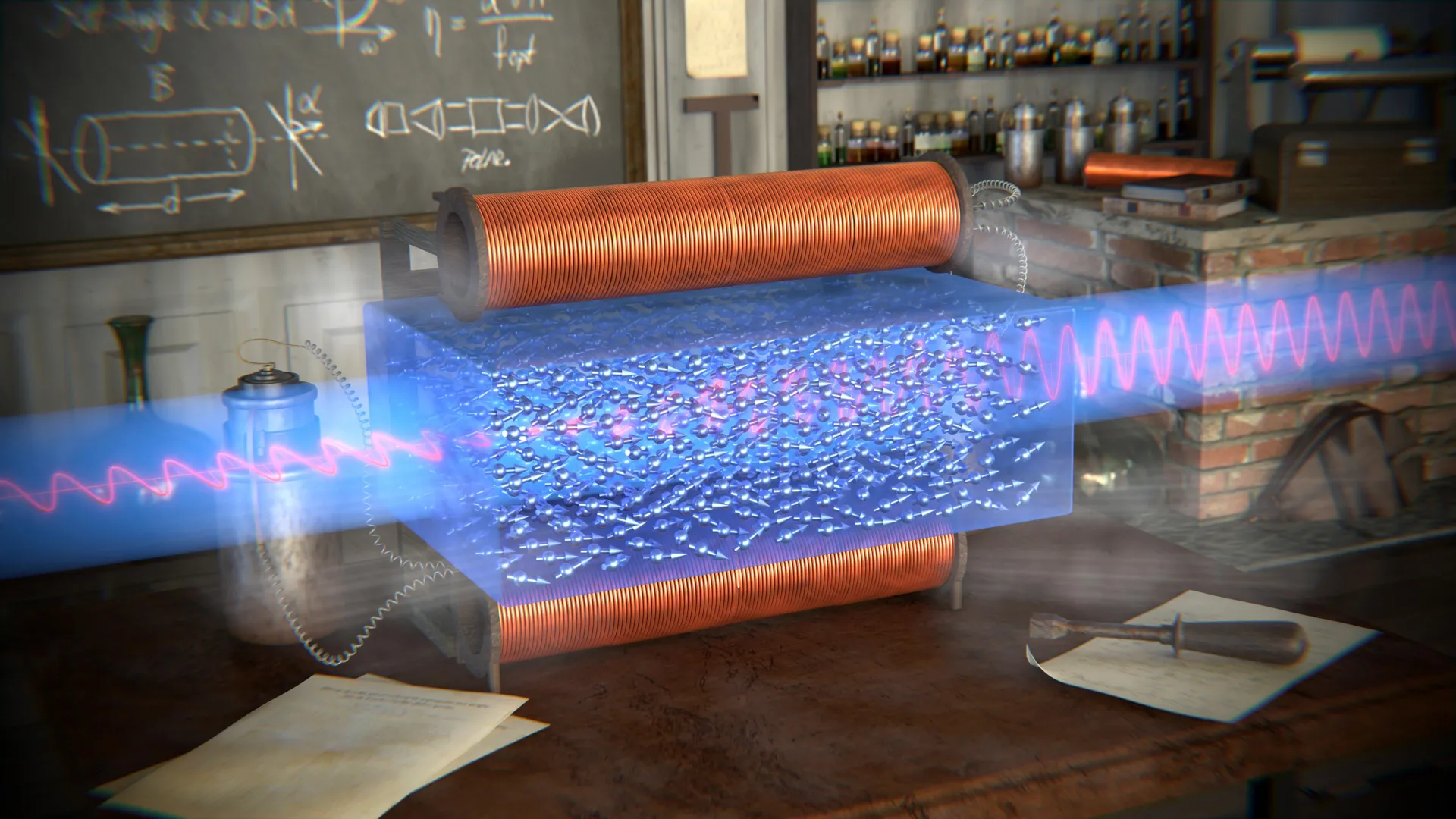

To understand why this rebound is so pronounced, it’s essential to delve into the mechanism of GLP-1 drugs. These medications mimic the action of a natural hormone, glucagon-like peptide-1, which is released in the gut in response to food intake. GLP-1 has several key functions: it stimulates insulin secretion (glucose-dependent), suppresses glucagon secretion, slows gastric emptying, and crucially, acts on the brain to increase satiety and reduce appetite. When these external GLP-1 agonists are removed, the body’s own hunger-regulating systems, which have been suppressed, often overcompensate. Hormones like ghrelin, often called the "hunger hormone," can surge, while natural satiety signals remain diminished, creating a powerful drive to eat that can feel overwhelming and relentless. This physiological "fight back" from the body, which perceives weight loss as a threat to survival, is a well-documented phenomenon in obesity research.

Beyond the biological mechanisms, the Oxford researchers also posited a behavioral explanation for the rapid regain. Senior author and Oxford associate professor Dimitrios Koutoukidis highlighted that "This faster regain could be because people using drugs don’t need to consciously practise changing their diet to lose weight, so when they stop taking the medication, they might not have developed the practical strategies that could help them keep it off." In essence, while GLP-1s powerfully suppress appetite, they don’t inherently teach sustainable dietary habits or foster the discipline required for long-term weight management. Patients may not develop the coping mechanisms or lifestyle modifications that are vital for maintaining weight loss once the pharmacological support is withdrawn.

The scientific community is now calling for a more nuanced and careful approach to the prescription and management of these drugs. Lead author and University of Oxford research scientist Sam West acknowledged the transformative power of GLP-1s, stating, "These medicines are transforming obesity treatment and can achieve important weight loss." However, he quickly added, "However, our research shows that people tend to regain weight rapidly after stopping — faster than we see with behavioral programs." West further emphasized that "This isn’t a failing of the medicines — it reflects the nature of obesity as a chronic, relapsing condition. It sounds a cautionary note for short-term use without a more comprehensive approach to long-term weight management, and highlights the importance of primary prevention."

This perspective underscores a fundamental truth about obesity: it is a complex, chronic disease influenced by genetics, environment, metabolism, and behavior, not simply a matter of willpower. Treating it as such means understanding that a temporary intervention, however effective, is unlikely to yield permanent results without sustained effort and support.

The implications of these findings are far-reaching. The cost of GLP-1 medications is substantial, often running into hundreds or even thousands of dollars per month without insurance coverage. The prospect of lifelong medication raises significant questions about accessibility, equity, and the sustainability of healthcare systems. If cessation is not viable for most, then these drugs shift from being a powerful tool for short-term intervention to a long-term, potentially lifelong, financial and medical commitment. This necessitates a re-evaluation of how these drugs are framed and prescribed, moving away from the "quick fix" narrative towards a model of chronic disease management.

Experts are advocating for a more holistic prescription model. Faye Riley, research communications lead at Diabetes UK, articulated this need to The Guardian, stating, "Weight loss drugs can be effective tools for managing weight and type 2 diabetes risk — but this research reinforces that they are not a quick fix. They need to be prescribed appropriately, with tailored wraparound support alongside them, to ensure people can fully benefit and maintain weight loss for as long as possible when they stop taking the medication." This "wraparound support" is crucial and would ideally include comprehensive dietary counseling from registered dietitians, personalized physical activity plans, psychological support to address emotional eating and body image, and behavioral therapy to develop sustainable coping strategies and habits.

Looking ahead, the scientific community is exploring various avenues to address these challenges. Research into combination therapies, which pair GLP-1s with other pharmacological agents targeting different metabolic pathways, holds promise for more durable weight loss and maintenance. Efforts are also underway to develop novel drugs that might induce more lasting metabolic changes, reducing the severity of the rebound effect. Furthermore, there’s an increased focus on primary prevention strategies to address obesity before it becomes a chronic condition requiring intensive medical intervention.

Ultimately, while GLP-1 drugs represent an astonishing leap forward in the treatment of obesity and related metabolic disorders, the emerging data on cessation highlights a critical need for a paradigm shift. They are not merely temporary aids but potent tools requiring careful, long-term strategic integration into comprehensive weight management plans. For patients, this means understanding the commitment involved and demanding the necessary support infrastructure. For healthcare providers, it means transparently setting expectations and prioritizing the provision of holistic, multidisciplinary care that extends far beyond the injection itself. The goal must be to harness the immense power of GLP-1s not just for immediate weight loss, but for sustainable health and well-being, acknowledging the profound challenges that arise when the medication stops. The sudden, terrible hunger upon cessation is a stark reminder that managing obesity is a marathon, not a sprint, and effective treatment demands sustained, integrated support.