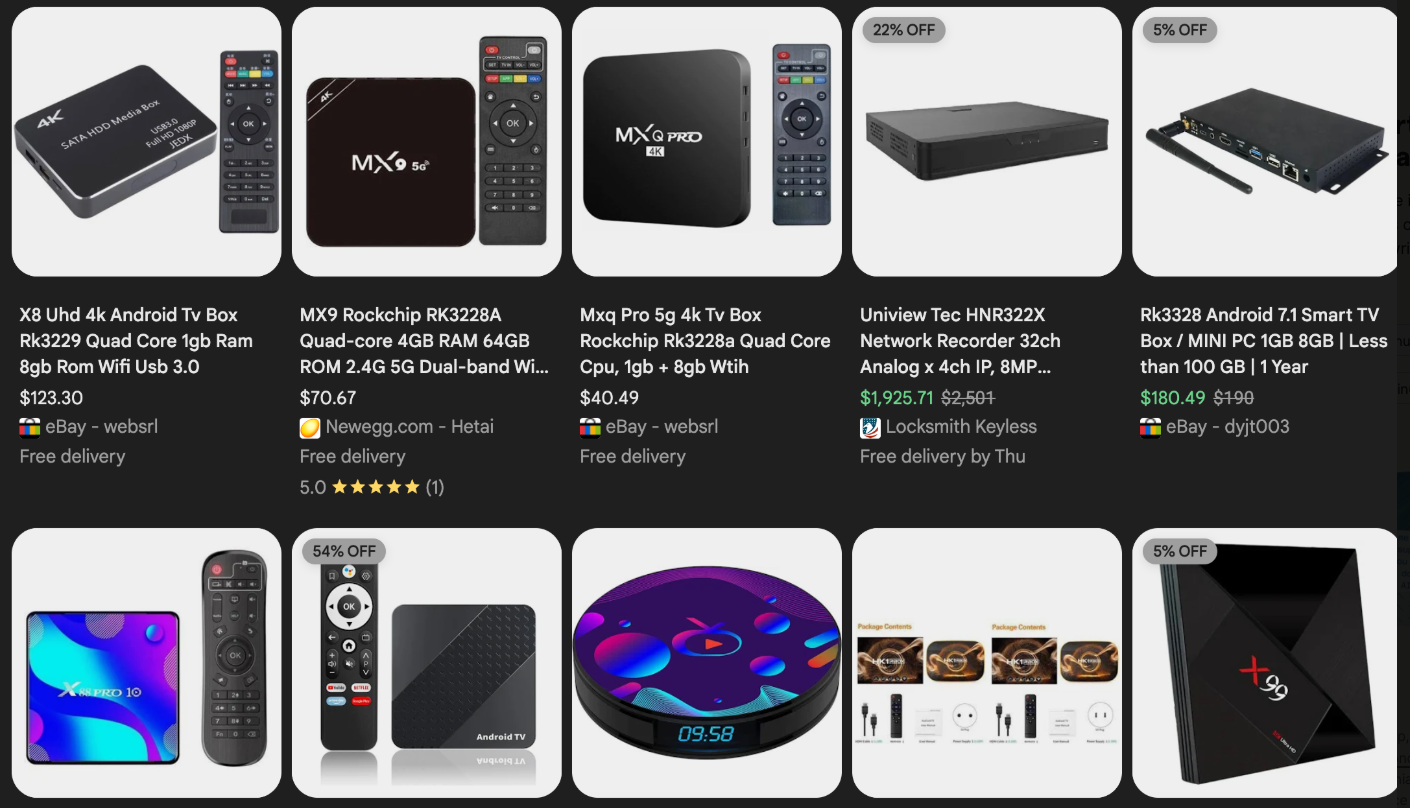

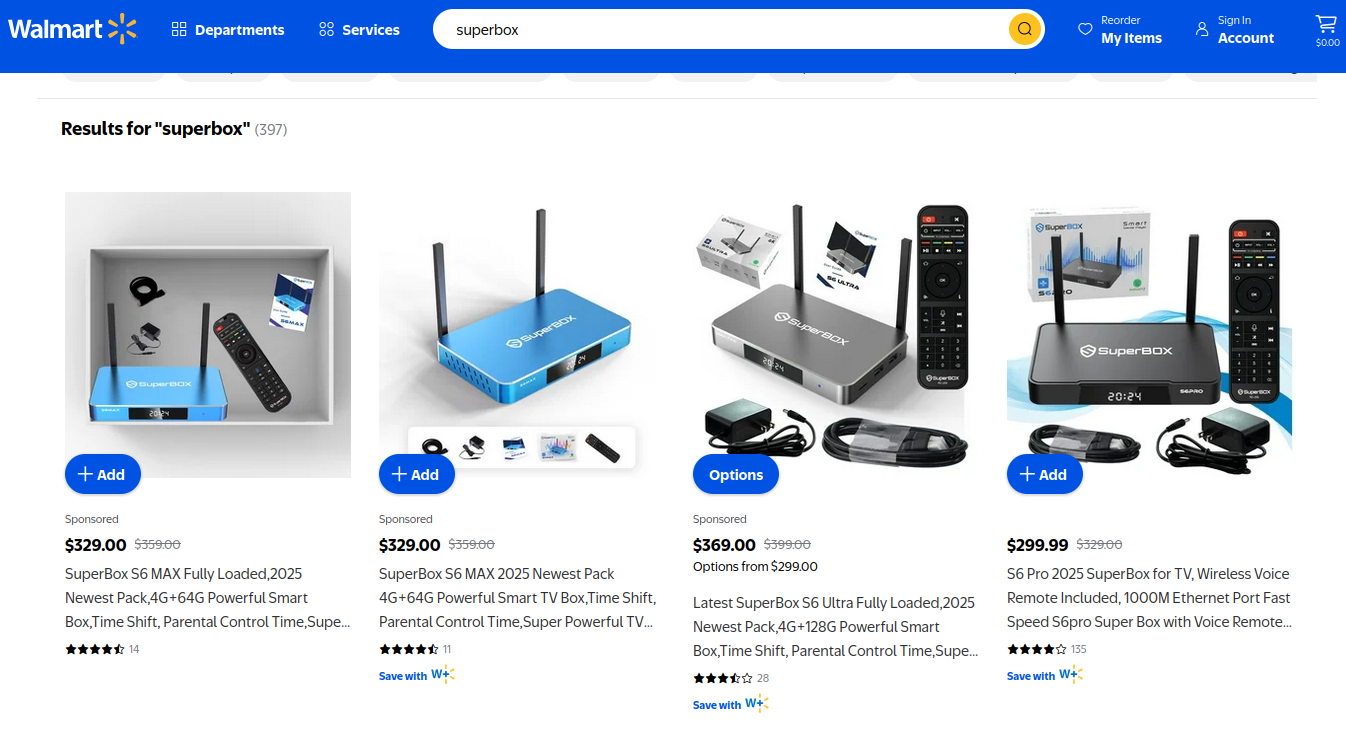

Residential proxy networks, marketed as a means for users to anonymize and localize their web traffic to specific regions, enable customers to route their internet activity through devices in virtually any geographic location. The malware that transforms an end-user’s internet connection into a proxy node is frequently bundled with untrustworthy mobile applications and games. Furthermore, these residential proxy programs are commonly installed via unofficial Android TV boxes, readily available from third-party sellers on major e-commerce platforms like Amazon, BestBuy, Newegg, and Walmart. These TV boxes, priced between $40 and $400, are marketed under a vast array of obscure brands and model numbers, often advertised as a way to stream subscription video content for free. However, this apparent bargain comes with a hidden cost: a substantial portion of the estimated two million Kimwolf infections originate from these very TV boxes.

Kimwolf also demonstrates a concerning proficiency in infecting a variety of internet-connected digital photo frames, which are equally prevalent on popular online marketplaces. In November 2025, researchers from Quokka published a report detailing severe security flaws in Android-based digital picture frames utilizing the Uhale app, including Amazon’s top-selling digital frame as of March 2025. These photo frames and unofficial Android TV boxes suffer from two primary security deficiencies. Firstly, a significant percentage arrive with pre-installed malware, or necessitate the download of unofficial Android app stores and malware to function as intended, often for video content piracy. The most common of these unwelcome additions are small programs that convert the device into a residential proxy node, which is then resold to others.

Secondly, a critical security vulnerability inherent in these devices and unsanctioned Android TV boxes lies in their reliance on a limited number of internet-connected microcomputer boards that lack any discernible security or authentication mechanisms. This means that any device connected to the same network as one or more of these compromised devices can potentially be compromised simultaneously with a single network command. This convergence of security weaknesses became starkly apparent in October 2025, when Benjamin Brundage, a 22-year-old undergraduate computer science student at the Rochester Institute of Technology and founder of the security firm Synthient, began meticulously tracking Kimwolf’s expansion and directly interacting with its suspected operators. Synthient specializes in detecting proxy networks and identifying their abuse.

While studying for final exams, Brundage shared his suspicions with KrebsOnSecurity in late October 2025 that Kimwolf was an Android-based variant of Aisuru, a botnet previously, and apparently incorrectly, implicated in a series of record-breaking DDoS attacks the previous fall. Brundage explained that Kimwolf’s rapid proliferation was fueled by its exploitation of a glaring vulnerability within many of the world’s largest residential proxy services. The core of this weakness, he elaborated, was the insufficient measures taken by these proxy services to prevent their customers from directing requests to the internal servers of individual proxy endpoints. Typically, proxy services implement basic safeguards to prevent customers from "going upstream" into the local network of proxy endpoints. This is usually achieved by explicitly denying requests targeting private IP address ranges defined in RFC-1918, which include the common Network Address Translation (NAT) ranges such as 10.0.0.0/8, 192.168.0.0/16, and 172.16.0.0/12. These ranges facilitate multiple devices within a private network sharing a single public IP address for internet access, and any home or office network operates within one or more of these NAT ranges.

However, Brundage’s investigation revealed that the operators of Kimwolf had devised a method to communicate directly with devices on the internal networks of millions of residential proxy endpoints. This was accomplished by manipulating their Domain Name System (DNS) settings to align with the RFC-1918 address ranges. "It is possible to circumvent existing domain restrictions by using DNS records that point to 192.168.0.1 or 0.0.0.0," Brundage detailed in a pioneering security advisory sent to nearly a dozen residential proxy providers in mid-December 2025. "This grants an attacker the ability to send carefully crafted requests to the current device or a device on the local network. This is actively being exploited, with attackers leveraging this functionality to drop malware." Similar to the digital photo frames discussed earlier, many of these residential proxy services operate on mobile devices running games, VPNs, or other applications with hidden components that effectively turn the user’s phone into a residential proxy, often without explicit consent.

In a report published concurrently with this news, Synthient stated that key actors involved in Kimwolf were observed monetizing the botnet through app installations, the sale of residential proxy bandwidth, and the provision of its DDoS capabilities. "Synthient expects to observe a growing interest among threat actors in gaining unrestricted access to proxy networks to infect devices, obtain network access, or access sensitive information," the report noted. "Kimwolf highlights the risks posed by unsecured proxy networks and their viability as an attack vector."

Further investigation by Brundage, involving the purchase of several unofficial Android TV box models heavily represented in the Kimwolf botnet, uncovered that the proxy service vulnerability was not the sole driver of Kimwolf’s rapid expansion. He discovered that virtually all tested devices were shipped from the factory with a powerful feature known as Android Debug Bridge (ADB) mode enabled by default. ADB is a diagnostic tool intended exclusively for manufacturing and testing processes, as it permits remote configuration and firmware updates, including potentially malicious ones. However, shipping devices with ADB enabled presents a significant security risk, as they continuously listen for and accept unauthenticated connection requests. For instance, executing a command like "adb connect [vulnerable device’s local IP address]:5555" can swiftly grant unrestricted "super user" administrative access.

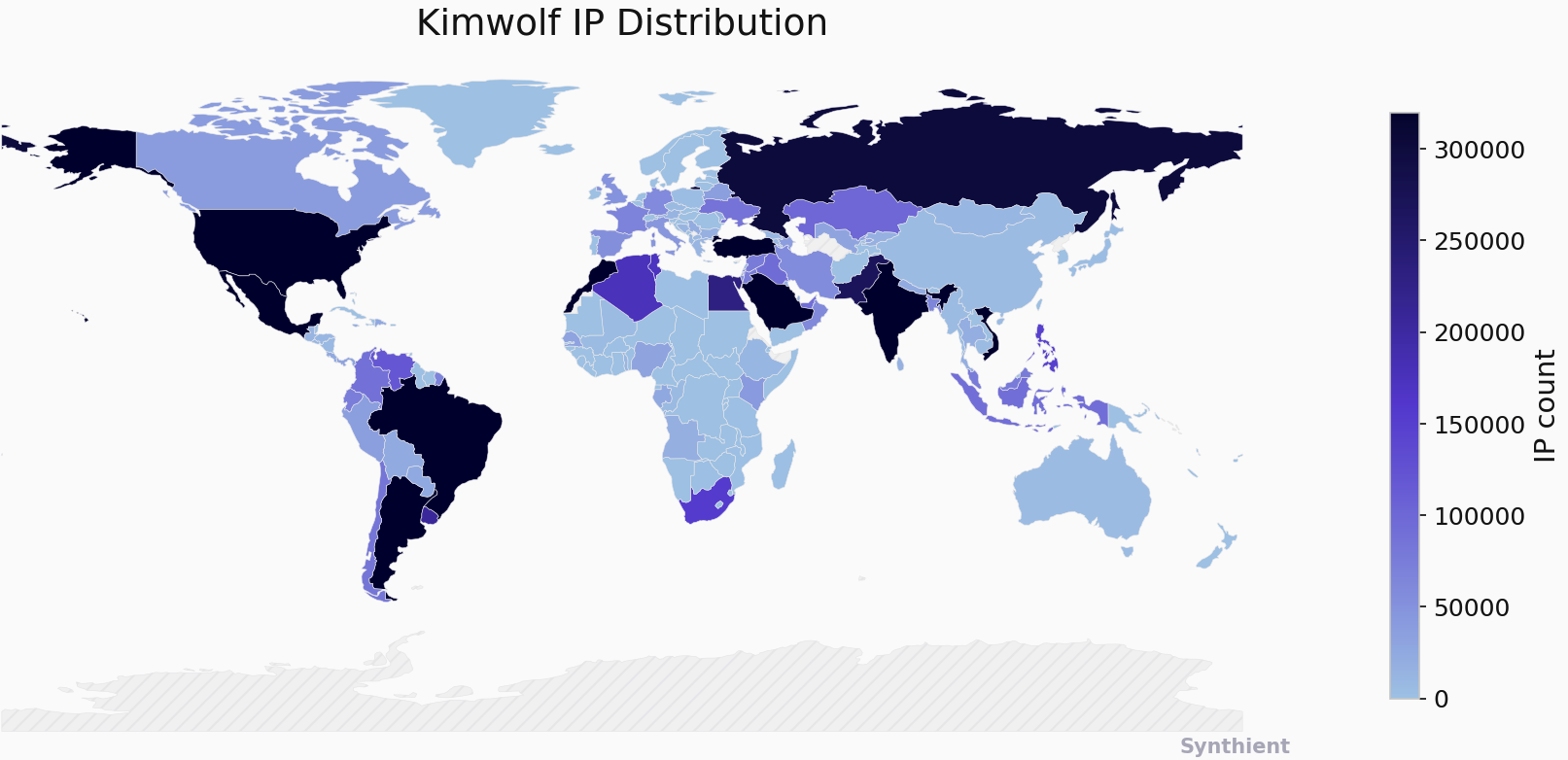

By early December, Brundage had identified a direct correlation between new Kimwolf infections and proxy IP addresses offered for rent by China-based IPIDEA, which is widely recognized as the world’s largest residential proxy network. "Kimwolf has almost doubled in size this past week, just by exploiting IPIDEA’s proxy pool," Brundage informed KrebsOnSecurity in early December, at which point he was preparing to notify IPIDEA and ten other proxy providers about his findings. Synthient confirmed on December 1, 2025, that Kimwolf botnet operators were tunneling through IPIDEA’s proxy network and accessing the local networks of systems running IPIDEA’s proxy software. The attackers deployed the malware payload by directing infected systems to a specific internet address and using the passphrase "krebsfiveheadindustries" to initiate the malicious download. By December 30, Synthient reported tracking approximately two million IPIDEA addresses exploited by Kimwolf in the preceding week. Brundage observed Kimwolf rapidly reconstituting itself, growing from nearly nothing to two million infected systems within a couple of days solely by tunneling through IPIDEA’s proxy endpoints after a previous takedown effort targeting its control servers.

Brundage highlighted IPIDEA’s seemingly inexhaustible supply of new proxies, with the company advertising access to over 100 million residential proxy endpoints globally in the past week alone. Synthient’s analysis of exposed devices within IPIDEA’s proxy pool revealed that more than two-thirds were Android devices susceptible to compromise without any authentication.

Brundage’s discovery of a strong overlap between Kimwolf-infected IP addresses and those sold by IPIDEA prompted him to expedite the public disclosure of his findings. The vulnerability had evidently been exploited for several months, though it appeared only a limited number of cybercriminals were aware of its potential. However, he recognized that going public without affording vulnerable proxy providers an opportunity to understand and rectify the issue would inevitably lead to broader abuse of these services by additional cybercriminal groups. On December 17, Brundage dispatched security notifications to all eleven apparently affected proxy providers, aiming to grant them several weeks to acknowledge and address the core problems identified in his report before public release. Many proxy providers receiving the notification were resellers of IPIDEA, white-labeling the company’s service.

KrebsOnSecurity first contacted IPIDEA for comment in October 2025, during reporting on a story suggesting the proxy network had benefited from the rise of the Aisuru botnet, whose administrators seemingly shifted focus from DDoS attacks to installing IPIDEA’s proxy program, among others. On December 25, KrebsOnSecurity received an email from an IPIDEA employee identified only as "Oliver," who dismissed allegations of IPIDEA benefiting from Aisuru’s growth as baseless. "After comprehensively verifying IP traceability records and supplier cooperation agreements, we found no association between any of our IP resources and the Aisuru botnet, nor have we received any notifications from authoritative institutions regarding our IPs being involved in malicious activities," Oliver stated. "In addition, for external cooperation, we implement a three-level review mechanism for suppliers, covering qualification verification, resource legality authentication and continuous dynamic monitoring, to ensure no compliance risks throughout the entire cooperation process." Oliver further asserted, "IPIDEA firmly opposes all forms of unfair competition and malicious smearing in the industry, always participates in market competition with compliant operation and honest cooperation, and also calls on the entire industry to jointly abandon irregular and unethical behaviors and build a clean and fair market ecosystem."

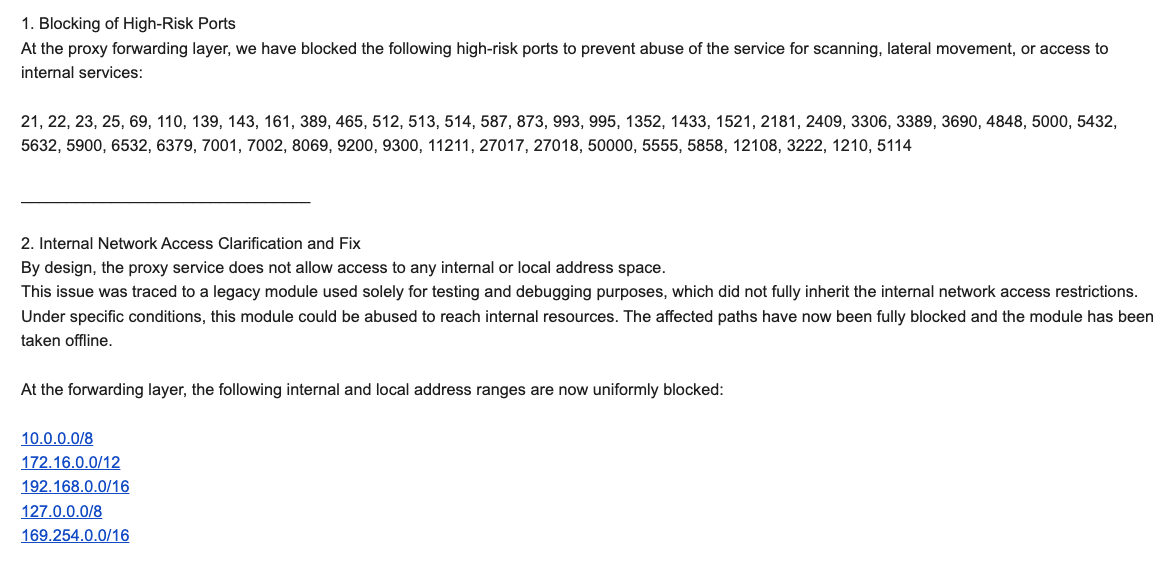

On the same day Oliver’s email was received, Brundage shared a response from IPIDEA’s security officer, identified only by the first name Byron. This security officer indicated that IPIDEA had implemented significant security enhancements to its residential proxy service to address the vulnerability outlined in Brundage’s report. "By design, the proxy service does not allow access to any internal or local address space," Byron explained. "This issue was traced to a legacy module used solely for testing and debugging purposes, which did not fully inherit the internal network access restrictions. Under specific conditions, this module could be abused to reach internal resources. The affected paths have now been fully blocked and the module has been taken offline." Byron further informed Brundage that IPIDEA had implemented multiple mitigations to block DNS resolution to internal (NAT) IP ranges and was now blocking proxy endpoints from forwarding traffic on "high-risk" ports "to prevent abuse of the service for scanning, lateral movement, or access to internal services." Brundage confirmed that IPIDEA appeared to have successfully patched the identified vulnerabilities, noting that he never observed Kimwolf actors targeting proxy services other than IPIDEA, which has not responded to further requests for comment.

Riley Kilmer, founder of Spur.us, a firm specializing in identifying and filtering proxy traffic, corroborated Brundage’s findings. Kilmer stated that Spur had tested Brundage’s research and confirmed that IPIDEA and all its affiliate resellers provided full and unfiltered access to local LANs. Kilmer pointed out that one particularly popular model of unsanctioned Android TV boxes, the Superbox (previously profiled by KrebsOnSecurity in November), leaves Android Debug Mode running on localhost:5555. "And since Superbox turns the IP into an IPIDEA proxy, a bad actor just has to use the proxy to localhost on that port and install whatever bad SDKs [software development kits] they want," Kilmer told KrebsOnSecurity.

Both Brundage and Kilmer suggest that IPIDEA represents the second or third iteration of a former residential proxy network known as 911S5 Proxy. This service operated from 2014 to 2022 and enjoyed considerable popularity on cybercrime forums. 911S5 Proxy imploded a week after KrebsOnSecurity published an in-depth analysis of the service’s questionable origins and leadership in China. In that 2022 report, researchers from the University of Sherbrooke in Canada highlighted the potential threat 911S5 posed to internal corporate networks, noting that "the infection of a node enables the 911S5 user to access shared resources on the network such as local intranet portals or other services." They further explained, "It also enables the end user to probe the LAN network of the infected node. Using the internal router, it would be possible to poison the DNS cache of the LAN router of the infected node, enabling further attacks." 911S5 initially responded to the 2022 reporting by claiming a comprehensive security review, but abruptly ceased operations just a week later, citing a malicious hacker who had destroyed all customer and payment records. In July 2024, the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned the alleged creators of 911S5, and the U.S. Department of Justice arrested the Chinese national named in the 2022 profile. Kilmer also mentioned that IPIDEA operates a sister service called 922 Proxy, which the company has actively promoted as a direct replacement for 911S5 Proxy. "You cannot tell me they don’t want the 911 customers by calling it that," Kilmer remarked. Among the recipients of Synthient’s security notification was the proxy giant Oxylabs. Brundage shared an email from Oxylabs’ security team dated December 31, acknowledging that Oxylabs had begun implementing security modifications to address the vulnerabilities detailed in Synthient’s report. Oxylabs confirmed to KrebsOnSecurity that they "have implemented changes that now eliminate the ability to bypass the blocklist and forward requests to private network addresses using a controlled domain." However, they stated there was no evidence that Kimwolf or other attackers had exploited their network. "In parallel, we reviewed the domains identified in the reported exploitation activity and did not observe traffic associated with them," the Oxylabs statement continued. "Based on this review, there is no indication that our residential network was impacted by these activities."

The practical implications of the Kimwolf botnet are significant, illustrating how mere Wi-Fi access can lead to infection. Consider a scenario where a guest, whose mobile phone is infected with an app turning it into a residential proxy node, connects to your Wi-Fi. Your home’s public IP address could then be listed for rent by a residential proxy provider. Malicious actors, like those behind Kimwolf, can then use these services to access your IP, tunnel back through it into your local area network (LAN), and automatically scan for devices with Android Debug Bridge mode enabled. By the time your guest departs, your network could host infected devices like a digital photo frame or an unofficial Android TV box, despite never intending for them to be exposed to the internet. Another alarming possibility is attackers modifying your internet router’s settings to use malicious DNS servers controlled by them, thereby dictating where your web browser directs you. This echoes the 2012 DNSChanger malware, which infected over half a million routers with search-hijacking malware, leading to the formation of an entire industry working group.

Much of the current information on Kimwolf originates from the Chinese security firm XLab, which first documented the rise of the Aisuru botnet in late 2024. In their latest blog post, XLab reported tracking Kimwolf on October 24, when its control servers were bombarding Cloudflare’s DNS servers with lookups for the distinctive domain 14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132[.]su. This domain and others linked to early Kimwolf variants spent several weeks topping Cloudflare’s chart of the internet’s most sought-after domains, surpassing even Google.com and Apple.com. This surge was due to Kimwolf instructing its millions of bots to check in frequently via Cloudflare’s DNS servers. XLab’s analysis indicates that Kimwolf had enslaved between 1.8 and 2 million devices, with significant concentrations in Brazil, India, the United States, and Argentina. It is now apparent that KrebsOnSecurity and other security experts may have misattributed some of Kimwolf’s early activities to the Aisuru botnet, which appears to be operated by a separate entity. While IPIDEA may have truthfully denied affiliation with Aisuru, Brundage’s data unequivocally demonstrated that its proxy service was being massively exploited by Kimwolf, the Android variant of Aisuru. XLab estimates Kimwolf has infected at least 1.8 million devices and has proven its capacity for rapid self-reconstruction. "Analysis indicates that Kimwolf’s primary infection targets are TV boxes deployed in residential network environments," XLab researchers stated. "Since residential networks usually adopt dynamic IP allocation mechanisms, the public IPs of devices change over time, so the true scale of infected devices cannot be accurately measured solely by the quantity of IPs. In other words, the cumulative observation of 2.7 million IP addresses does not equate to 2.7 million infected devices." XLab also notes that measuring Kimwolf’s size is challenging due to the distribution of infected devices across multiple global time zones. "Affected by time zone differences and usage habits (e.g., turning off devices at night, not using TV boxes during holidays, etc.), these devices are not online simultaneously, further increasing the difficulty of comprehensive observation through a single time window," the blog post observed. XLab further points out the Kimwolf author’s "obsessive" fixation on the author of this article, apparently embedding "easter eggs" related to the author’s name within the botnet’s code and communications.

A frustrating aspect of threats like Kimwolf is the difficulty for average users to determine if vulnerable devices are present on their internal networks or already infected with residential proxy malware. Even if one could identify a specific mobile device responsible for residential proxy activity on their network, isolating and removing the offending app or component would still be necessary. The necessary tooling and expertise for such detailed visibility are beyond the reach of most consumers. However, Synthient has launched a website where visitors can check if their public internet address has been observed among Kimwolf-infected systems. Brundage has also compiled a list of unofficial Android TV boxes most heavily represented in the Kimwolf botnet. Users possessing TV boxes matching these model names or numbers are strongly advised to immediately remove them from their networks. If such devices are encountered on the network of a friend or family member, sharing this article and explaining the potential harm of keeping them connected is crucial.

Chad Seaman, a principal security researcher at Akamai Technologies, emphasizes the need for greater consumer vigilance against these pseudo Android TV boxes and residential proxy schemes. "We need to highlight why they’re dangerous to everyone and to the individual," Seaman stated. "The whole security model where people think their LAN (Local Internal Network) is safe, that there aren’t any bad guys on the LAN so it can’t be that dangerous is just really outdated now." He added, "The idea that an app can enable this type of abuse on my network and other networks, that should really give you pause," regarding device selection for local networks. "And it’s not just Android devices here. Some of these proxy services have SDKs for Mac and Windows, and the iPhone. It could be running something that inadvertently cracks open your network and lets countless random people inside." In July 2025, Google filed a lawsuit against 25 unidentified defendants collectively dubbed "BadBox 2.0 Enterprise," describing a botnet of over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. Google alleged that the BADBOX 2.0 botnet, in addition to compromising devices before purchase, could infect them through malicious apps downloaded from unofficial marketplaces. This lawsuit followed a June 2025 advisory from the FBI, warning that cybercriminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by pre-installing malware or infecting devices during setup via malicious applications. The FBI identified BADBOX 2.0 after the original BADBOX campaign was disrupted in 2024; the original BADBOX, primarily consisting of Android devices compromised with backdoor malware before purchase, was identified in 2023.

Lindsay Kaye, vice president of threat intelligence at HUMAN Security, a company involved in the BADBOX investigations, stated that the BADBOX botnets and the residential proxy networks riding on compromised devices were detected due to their extensive involvement in advertising fraud, ticket scalping, retail fraud, account takeovers, and content scraping. Kaye advises consumers to stick to reputable brands for devices requiring wired or wireless connections. "If people are asking what they can do to avoid being victimized by proxies, it’s safest to stick with name brands," Kaye said. "Anything promising something for free or low-cost, or giving you something for nothing just isn’t worth it. And be careful about what apps you allow on your phone." Many modern wireless routers offer a "Guest" network option, allowing visitors internet access while preventing their devices from communicating with other local network devices. When guests, contractors, or even family members request network access, utilizing the guest Wi-Fi credentials is a recommended security measure. A small but vocal pro-piracy faction dismisses the security risks posed by these unsanctioned Android TV boxes, arguing that internet-connected devices are neutral and that even factory-infected boxes can be re-flashed with custom firmware. However, the majority of consumers acquiring these devices are not security or hardware experts; they are drawn by the promise of "free" content. Most buyers are unaware of the inherent risks when connecting these dubious TV boxes to their networks. It is notable that the entertainment industry has not exerted more visible pressure on major e-commerce vendors to cease selling this insecure and actively malicious hardware, largely marketed for video piracy. These TV boxes represent a public nuisance due to their bundled malicious software and lack of apparent security or authentication, making them an attractive target for cybercriminals. Further revelations concerning the individuals who appear to have built and benefited most from Kimwolf are anticipated in Part II of this series.