Quantum computers, poised to revolutionize fields from fundamental physics and chemistry to drug discovery and materials science, are on the cusp of a significant leap forward, thanks to a groundbreaking achievement by physicists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). These next-generation computing machines, which harness the enigmatic principles of quantum mechanics, require an immense number of qubits – the quantum equivalent of classical bits – to tackle the most complex computational challenges. Unlike classical bits that represent either a 0 or a 1, qubits can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously. This remarkable quantum phenomenon imbues quantum computers with the potential to outperform their classical counterparts in specific, intricate calculations. However, this power comes with a significant caveat: qubits are inherently fragile and susceptible to errors. To mitigate this fragility and ensure the reliability of quantum computations, researchers are developing strategies to build quantum computers with a substantial number of redundant qubits, enabling sophisticated error correction mechanisms. The ultimate vision for robust, fault-tolerant quantum computers necessitates hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of these delicate quantum bits.

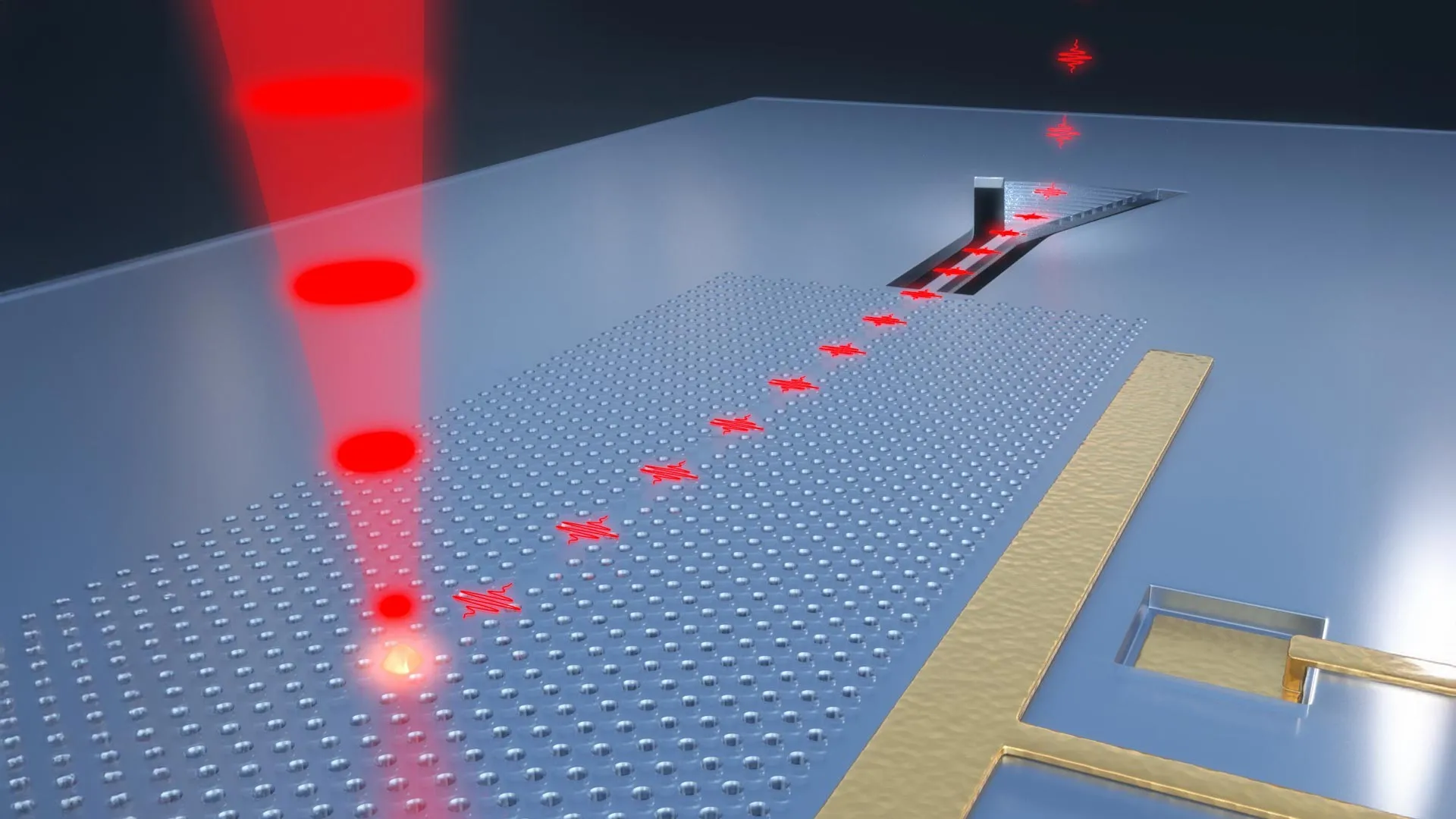

In a pivotal step toward realizing this ambitious future, Caltech physicists have successfully engineered and assembled the largest neutral-atom qubit array ever created, comprising a staggering 6,100 qubits. These qubits, individual cesium atoms, are meticulously trapped and arranged in a highly ordered grid using precisely controlled laser beams, a technique often referred to as optical tweezers. This achievement dwarfs previous arrays of this nature, which typically contained only hundreds of qubits. The development arrives amidst a rapidly intensifying global race to scale up quantum computing technology, with various promising approaches vying for supremacy. These include quantum computers based on superconducting circuits, trapped ions, and the neutral-atom platform that forms the basis of the new Caltech study.

"This is an exciting moment for neutral-atom quantum computing," declared Manuel Endres, a professor of physics at Caltech and the principal investigator of the research. "We can now see a clear pathway to large error-corrected quantum computers. The fundamental building blocks are in place." The pioneering research, published on September 24th in the prestigious journal Nature, was spearheaded by three Caltech graduate students: Hannah Manetsch, Gyohei Nomura, and Elie Bataille.

The Caltech team’s innovative approach involved utilizing optical tweezers – tightly focused laser beams – to meticulously capture thousands of individual cesium atoms within a vacuum chamber. To construct the vast qubit array, the researchers ingeniously split a single laser beam into an astonishing 12,000 individual tweezers, which collectively held 6,100 atoms in their precise grid formation. "On the screen, we can actually see each qubit as a pinpoint of light," Manetsch explained, offering a vivid description of the quantum hardware at such an unprecedented scale. "It’s a striking image of quantum hardware at a large scale."

A particularly significant achievement of this research lies in demonstrating that this dramatic increase in scale did not come at the expense of qubit quality. Even with over 6,000 qubits coexisting within a single array, the researchers managed to maintain their delicate superposition states for approximately 13 seconds, a duration nearly 10 times longer than what was previously achievable in comparable neutral-atom arrays. Furthermore, the team demonstrated the ability to individually manipulate these qubits with an exceptional accuracy of 99.98 percent. "Large scale, with more atoms, is often thought to come at the expense of accuracy, but our results show that we can do both," Nomura emphasized, highlighting the dual triumph of quantity and quality. "Qubits aren’t useful without quality. Now we have quantity and quality."

The researchers also showcased another critical capability: the ability to move individual atoms across the array over distances of hundreds of micrometers while preserving their quantum superposition. This "shuttling" of qubits is a key advantage of neutral-atom quantum computers, enabling more efficient and flexible error correction compared to traditional, hard-wired platforms like those based on superconducting qubits. Manetsch likened the complex task of moving individual atoms while maintaining their superposition to the delicate act of balancing a glass of water while running. "Trying to hold an atom while moving is like trying to not let the glass of water tip over. Trying to also keep the atom in a state of superposition is like being careful to not run so fast that water splashes over," she eloquently explained.

The next major hurdle for the field is the implementation of quantum error correction on a scale involving thousands of physical qubits. This latest work provides compelling evidence that neutral atoms are a highly promising candidate for achieving this crucial milestone. "Quantum computers will have to encode information in a way that’s tolerant to errors, so we can actually do calculations of value," stated Bataille, underscoring the necessity of error correction for practical quantum computation. He further elaborated on a fundamental difference between quantum and classical computing: "Unlike in classical computers, qubits can’t simply be copied due to the so-called no-cloning theorem, so error correction has to rely on more subtle strategies."

Looking toward the horizon, the Caltech team plans to further enhance their system by linking the qubits within their array into entangled states. Entanglement is a phenomenon where quantum particles become correlated, behaving as a single, unified entity, regardless of the physical distance separating them. This is an essential step for quantum computers to progress beyond mere information storage in superposition and to begin executing full-fledged quantum computations. It is precisely this ability to harness entanglement that imbues quantum computers with their ultimate power – the capacity to simulate the intricacies of nature itself. Entanglement plays a fundamental role in shaping the behavior of matter at every scale, from the subatomic to the cosmological. The overarching goal is clear: to leverage entanglement to unlock profound new scientific discoveries, including the revelation of novel phases of matter, the design of advanced materials with unprecedented properties, and the accurate modeling of the quantum fields that govern the fabric of space-time.

"It’s exciting that we are creating machines to help us learn about the universe in ways that only quantum mechanics can teach us," Manetsch concluded with palpable enthusiasm, encapsulating the profound implications of their work for fundamental scientific inquiry.

The groundbreaking study, titled "A tweezer array with 6100 highly coherent atomic qubits," received substantial funding from a consortium of esteemed institutions, including the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Weston Havens Foundation, the National Science Foundation through its Graduate Research Fellowship Program, the Institute for Quantum Information and Matter (IQIM) at Caltech, the Army Research Office, the U.S. Department of Energy (including its Quantum Systems Accelerator), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Air Force Office for Scientific Research, the Heising-Simons Foundation, and the AWS Quantum Postdoctoral Fellowship. Additional contributions to the research came from Caltech’s Kon H. Leung, an AWS Quantum senior postdoctoral scholar research associate in physics, and former Caltech postdoctoral scholar Xudong Lv, now affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences.