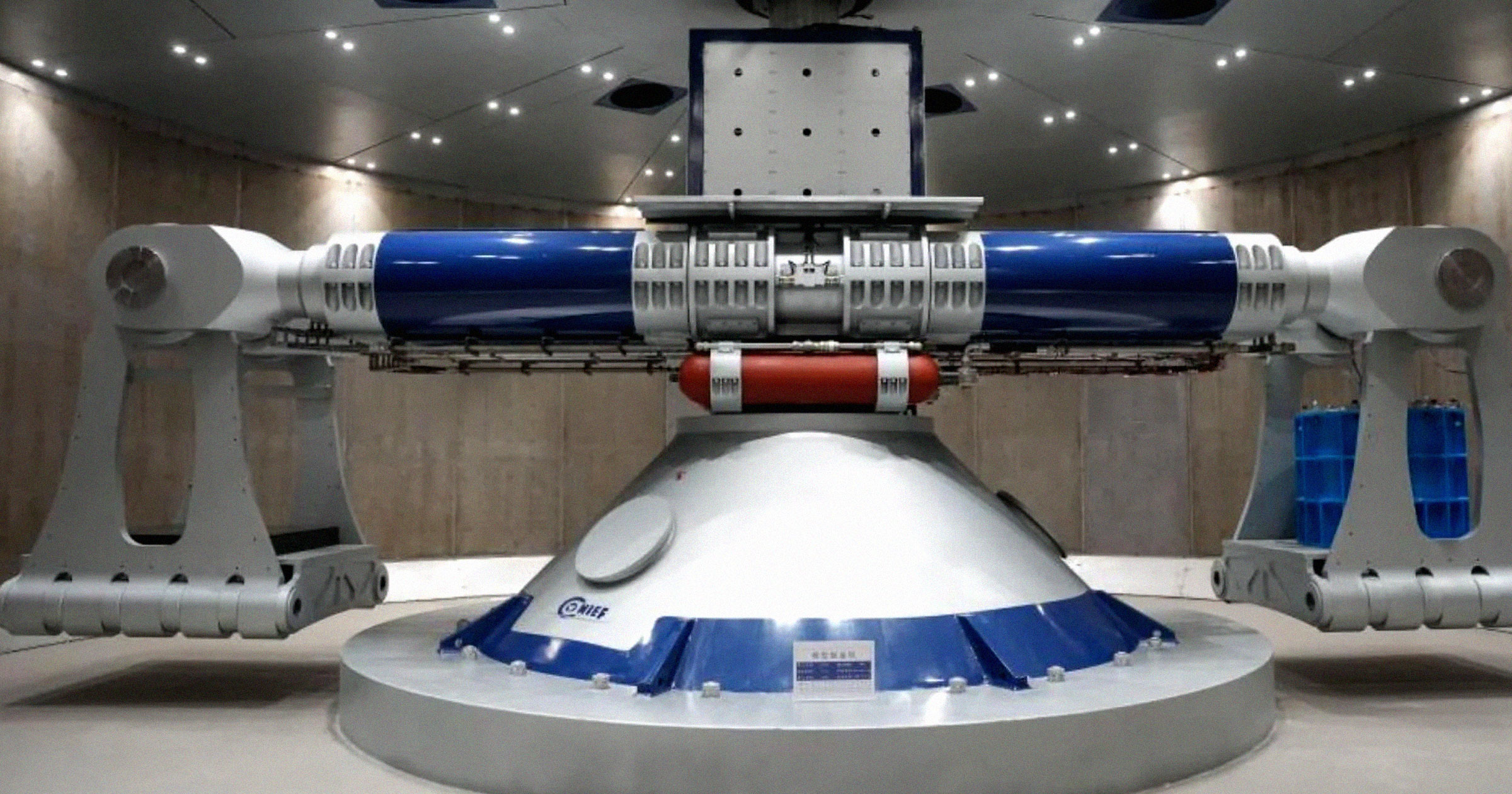

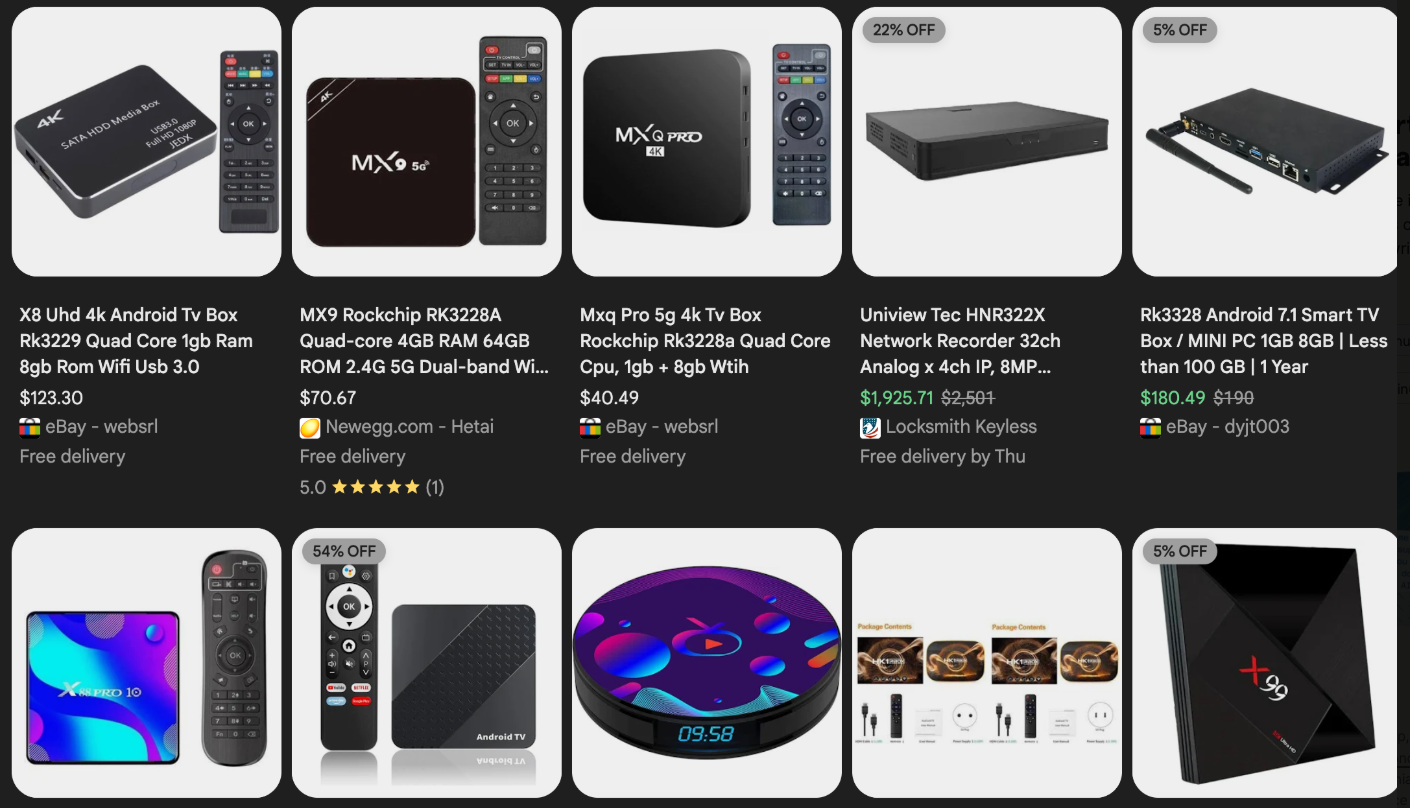

Residential proxy networks, marketed as tools for anonymity and geo-localization of internet traffic, allow users to route their online activity through a vast network of devices worldwide. However, the malware responsible for transforming ordinary internet connections into these proxy nodes is often bundled with dubious mobile applications, games, and, most disturbingly, unofficial Android TV boxes. These devices, readily available on major e-commerce platforms like Amazon, Best Buy, Newegg, and Walmart, are frequently marketed under obscure brands and promise free access to subscription video content, masking a hidden, dangerous cost. Ranging from $40 to $400, these TV boxes are a significant vector for Kimwolf infections, with Synthient reporting that two-thirds of the botnet’s compromised devices are these insecure Android TV boxes.

Beyond TV boxes, Kimwolf has also demonstrated a proficiency in infecting internet-connected digital photo frames. A November 2025 report by Quokka highlighted severe security flaws in Android-based digital picture frames running the Uhale app, including Amazon’s top-selling model as of March 2025. The core security issues with these devices, including the unofficial Android TV boxes, are twofold. Firstly, many come pre-loaded with malware or require users to download unofficial app stores and malware to function as advertised, often for content piracy. These malicious components frequently turn the device into a residential proxy node, resold to other users. Secondly, these devices rely on microcomputer boards lacking any built-in security or authentication. This means that any device on the same network can potentially compromise them with a single command, creating a widespread vulnerability.

The convergence of these security failures became starkly apparent in October 2025 when Benjamin Brundage, a 22-year-old undergraduate computer science student at the Rochester Institute of Technology and founder of the security firm Synthient, began tracking Kimwolf’s growth. Brundage suspected Kimwolf was an Android-based variant of the Aisuru botnet, which had been wrongly implicated in record-breaking DDoS attacks. Kimwolf’s rapid expansion, Brundage explained, was due to its exploitation of a critical vulnerability in many large residential proxy services. The flaw lay in insufficient safeguards against customers forwarding requests to the internal servers of proxy endpoints. While most proxy services attempt to prevent "upstream" access into local networks by blocking RFC-1918 private IP address ranges (10.0.0.0/8, 192.168.0.0/16, and 172.16.0.0/12), the Kimwolf operators discovered a way to bypass these restrictions.

By manipulating Domain Name System (DNS) settings to align with RFC-1918 address ranges, Brundage found that attackers could directly communicate with devices on the internal networks of residential proxy endpoints. "It is possible to circumvent existing domain restrictions by using DNS records that point to 192.168.0.1 or 0.0.0.0," Brundage stated in a security advisory sent to proxy providers in mid-December 2025. "This grants an attacker the ability to send carefully crafted requests to the current device or a device on the local network. This is actively being exploited, with attackers leveraging this functionality to drop malware." Similar to the digital photo frames, many residential proxy services operate on mobile devices running apps with hidden components that turn the user’s phone into a proxy, often without explicit consent. Synthient’s report indicated that Kimwolf actors were monetizing the botnet through app installs, selling proxy bandwidth, and offering DDoS capabilities, predicting a rise in threat actors seeking unrestricted access to proxy networks for various nefarious purposes.

Further investigation by Brundage into unofficial Android TV boxes revealed another significant factor in Kimwolf’s proliferation: the default activation of Android Debug Bridge (ADB) mode. ADB, a diagnostic tool intended for manufacturing and testing, allows remote configuration and firmware updates. However, when enabled by default, it creates a security vulnerability by constantly listening for and accepting unauthenticated connection requests. A simple command like "adb connect [device’s local IP]:5555" can grant unrestricted administrative access. Brundage identified a direct correlation between new Kimwolf infections and proxy IP addresses rented by IPIDEA, identified as the world’s largest residential proxy network. By early December, Kimwolf had nearly doubled in size by exploiting IPIDEA’s proxy pool. Synthient confirmed on December 1, 2025, that Kimwolf operators were tunneling through IPIDEA’s network to access local systems, dropping malware by directing infected devices to a specific address and using the passphrase "krebsfiveheadindustries" to unlock the malicious download. By December 30, Synthient was tracking approximately two million IPIDEA addresses exploited by Kimwolf in the preceding week, with the botnet demonstrating a remarkable ability to rebuild itself rapidly after takedown attempts by leveraging IPIDEA’s vast proxy supply. Synthient’s analysis of IPIDEA’s pool revealed that over two-thirds of the exposed devices were unauthenticated Android devices, highly susceptible to compromise.

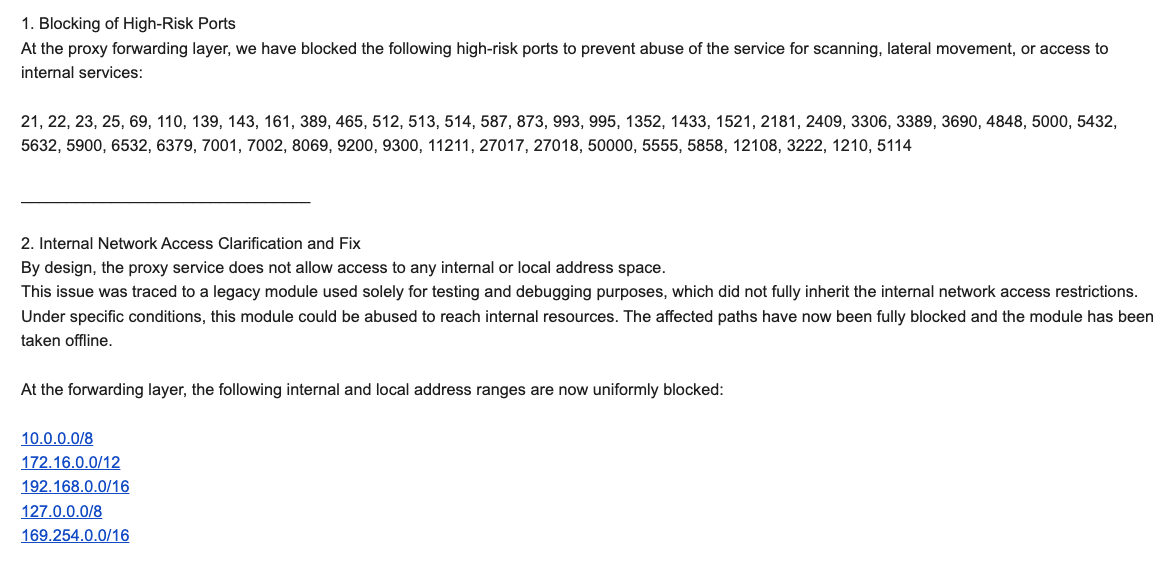

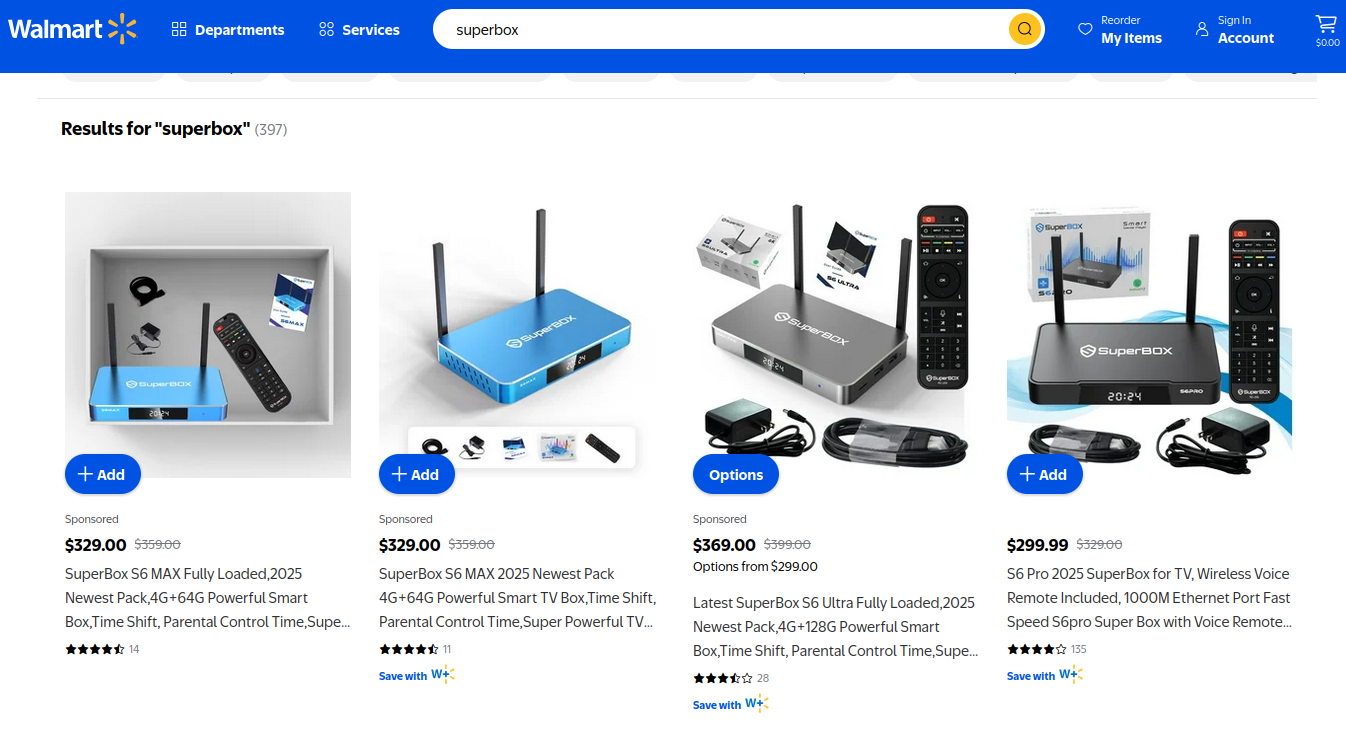

Brundage, after observing the direct overlap between Kimwolf-infected IPs and those sold by IPIDEA, sought to publicize his findings. Recognizing the potential for widespread abuse if unpatched, he sent security notifications to 11 affected proxy providers on December 17, aiming to provide them with several weeks to address the vulnerabilities. Many of these providers were resellers of IPIDEA’s services. KrebsOnSecurity had previously contacted IPIDEA in October 2025 regarding its apparent benefit from the Aisuru botnet’s shift towards proxy services. An IPIDEA employee named "Oliver" denied any association with the Aisuru botnet, citing rigorous supplier verification processes. However, on the same day Oliver’s email was received, Brundage shared a response from IPIDEA’s security officer, "Byron," who acknowledged that a legacy testing module within the proxy service had allowed unauthorized access to internal network resources. Byron stated that this module had been disabled, all affected paths blocked, and that IPIDEA had implemented mitigations to block DNS resolution to internal IP ranges and to prevent traffic forwarding on high-risk ports. Brundage confirmed that IPIDEA appeared to have patched the vulnerabilities, noting that he had not observed Kimwolf targeting other proxy services. Riley Kilmer, founder of Spur.us, independently verified that IPIDEA and its affiliates provided unfiltered access to local LANs, highlighting the Superbox, a popular unsanctioned Android TV box, as a prime example that leaves ADB running on localhost:5555, making it an easy target when combined with IPIDEA’s proxy service.

Both Brundage and Kilmer suggest that IPIDEA is a successor to the notorious 911S5 Proxy, a service that operated from 2014 to 2022 and was popular on cybercrime forums before imploding after a data breach. The 911S5 service had similar vulnerabilities, allowing users to access shared resources on infected networks and probe LANs. The U.S. Treasury later sanctioned the alleged creators of 911S5, and the Department of Justice arrested a key figure. Kilmer also pointed to IPIDEA’s sister service, 922 Proxy, as a direct attempt to capture 911S5’s former customer base. Oxylabs, another proxy provider that received Synthient’s notification, confirmed implementing security changes to prevent bypassing blocklists and forwarding requests to private network addresses, though they reported no evidence of Kimwolf exploiting their network.

The practical implications of Kimwolf are significant. A scenario where a friend’s infected phone, used on your Wi-Fi, turns your home IP into a proxy node, allowing attackers to tunnel back into your local network and infect devices like digital photo frames and Android TV boxes, is entirely plausible. Attackers could also exploit this access to alter your router’s DNS settings, redirecting your web traffic to malicious servers, reminiscent of the 2012 DNSChanger malware.

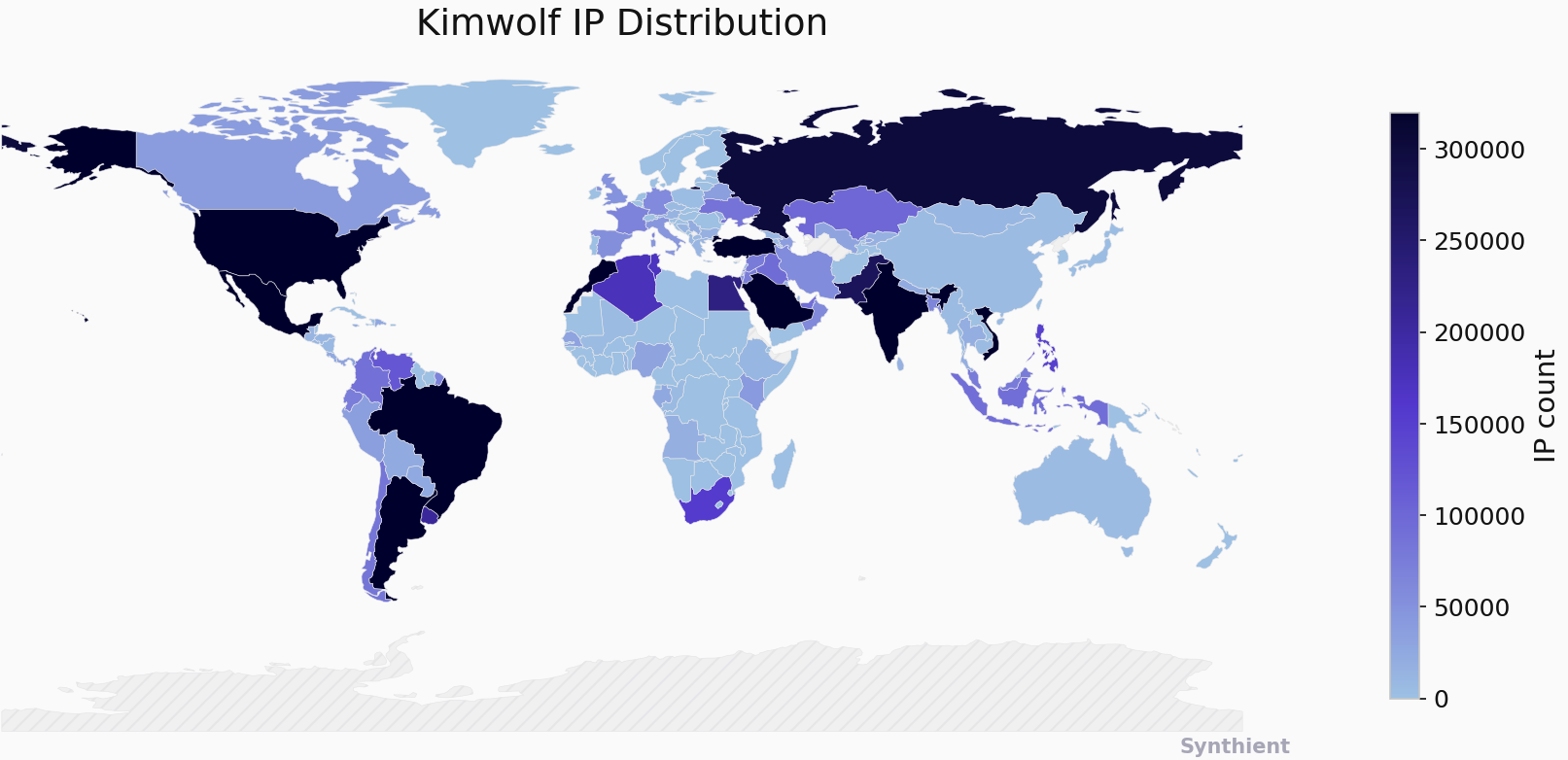

The Chinese security firm XLab has also been instrumental in chronicling Kimwolf’s rise, initially tracking it in late October and noting its control servers overwhelming Cloudflare’s DNS servers. XLab estimated Kimwolf had enslaved between 1.8 and two million devices, with significant concentrations in Brazil, India, the United States, and Argentina. XLab’s analysis suggests that Kimwolf’s primary targets are TV boxes in residential environments, and accurately measuring the botnet’s scale is challenging due to dynamic IP allocation and devices not being online simultaneously. Interestingly, XLab noted an "obsessive" fixation by the Kimwolf author on "Yours Truly," embedding "easter eggs" within the botnet’s code. While XLab’s findings align with Synthient’s, it’s important to clarify that earlier attributions of some activities to the Aisuru botnet may have been misinterpretations, with Kimwolf appearing to be operated by a distinct group, though IPIDEA’s proxy service was clearly being massively abused by Kimwolf.

Identifying Kimwolf infections or residential proxy malware on a home network is difficult for average users, as it requires advanced tooling and network analysis skills. However, Synthient offers a web page where visitors can check if their public IP address has been observed among Kimwolf-infected systems. They have also compiled a list of unofficial Android TV boxes most represented in the Kimwolf botnet. Users with devices matching these models are strongly advised to remove them from their network. Chad Seaman of Akamai Technologies urges consumers to be highly skeptical of these unofficial Android TV boxes and residential proxy schemes, emphasizing that the notion of a safe internal LAN is outdated, as compromised devices can inadvertently expose entire networks. He notes that the threat extends beyond Android, with proxy SDKs available for Mac, Windows, and iPhones.

Google’s lawsuit against "BadBox 2.0 Enterprise" in July 2025, targeting over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices involved in ad fraud, and an FBI advisory in June 2025 warning of pre-purchase malware infections on home network devices, underscore the pervasive nature of this threat. Lindsay Kaye of HUMAN Security, who worked on BADBOX investigations, stressed the importance of sticking to name brands for connected devices and being wary of free or low-cost offers, as well as the apps installed on phones. She also recommended using guest Wi-Fi networks for visitors to isolate their devices from the local network. While some advocate for reflashing these devices with custom firmware, the majority of consumers purchasing them are not security experts and are unaware of the risks involved, often seeking free content. The entertainment industry’s lack of visible pressure on e-commerce vendors to cease selling these insecure, actively malicious hardware products, largely designed for video piracy, remains a notable omission. The series will continue with Part II, delving into clues left by those who have benefited most from Kimwolf.