Direct navigation, the practice of typing a website’s domain name directly into a web browser, has become significantly more perilous, according to a recent study by cybersecurity firm Infoblox. The research reveals that a substantial majority of "parked" domains—which typically comprise expired or dormant domain names, or common misspellings of popular websites—are now intentionally configured to redirect unsuspecting visitors to sites peddling scams and malware. This alarming trend marks a stark reversal from a decade ago, when such domains posed a relatively low risk.

Traditionally, when internet users attempted to visit expired domain names or inadvertently landed on a "typosquatting" domain (a domain that closely resembles a legitimate one), they would be presented with a placeholder page managed by a domain parking company. These companies aimed to monetize the traffic by displaying advertisements and links to various third-party websites that had paid for placement. However, a study conducted in 2014 by USENIX found that parked domains redirected users to malicious sites in less than five percent of instances, even without any user interaction with the displayed links.

Infoblox’s recent extensive experiments, conducted over several months, paint a vastly different picture. Their findings indicate that the situation has inverted, with malicious content now being the overwhelming norm for parked websites. "In large scale experiments, we found that over 90% of the time, visitors to a parked domain would be directed to illegal content, scams, scareware and anti-virus software subscriptions, or malware, as the ‘click’ was sold from the parking company to advertisers, who often resold that traffic to yet another party," Infoblox researchers detailed in a white paper published today.

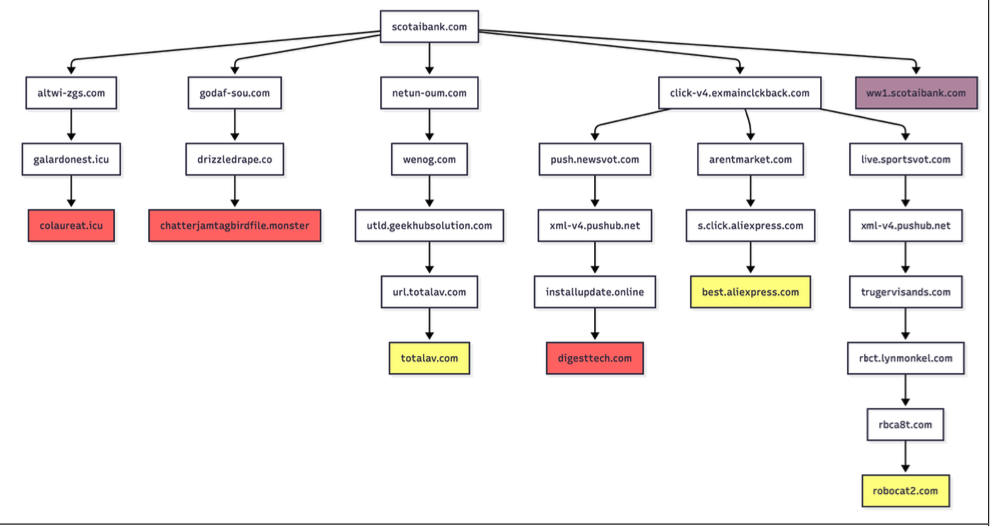

The study highlights a critical distinction: parked websites appear benign when accessed via a virtual private network (VPN) or from a non-residential internet address. However, users connecting through residential IP addresses, whether on desktop or mobile devices, are immediately subjected to malicious redirection. For instance, a customer of Scotiabank who mistypes the domain as "scotaibank[.]com" would encounter a standard parking page if using a VPN. In contrast, a user with a residential IP address would be swiftly redirected to a site attempting to push scams, malware, or other unwanted content simply by visiting the misspelled domain.

Infoblox identified a specific threat actor operating under the domain "scotaibank[.]com," who possesses a portfolio of nearly 3,000 similar domains. This portfolio includes egregious examples like "gmai[.]com," which has been equipped with its own mail server. This means that emails intended for legitimate Gmail users, if misspelled by omitting the "l," are not lost but are instead intercepted and directed to these scammers. The report notes that this domain has been a vector in numerous recent business email compromise (BEC) campaigns, often employing lures related to failed payments and attaching trojan malware.

Further investigation by Infoblox revealed that this particular domain holder, identifiable through the common DNS server "torresdns[.]com," has established typosquatting domains targeting dozens of prominent internet destinations. This list includes major platforms such as Craigslist, YouTube, Google, Wikipedia, Netflix, TripAdvisor, Yahoo, eBay, and Microsoft. A sanitized list of these typosquatting domains, with dots replaced by commas for safety, has been made available.

David Brunsdon, a threat researcher at Infoblox, explained the sophisticated redirection mechanisms employed. Parked pages initiate a chain of redirects, during which visitor systems are profiled using IP geolocation, device fingerprinting, and cookies. This profiling determines the ultimate destination, which could be a malicious domain or, if the visitor is deemed an unprofitable target, a decoy page mimicking legitimate sites like Amazon.com or Alibaba.com. "It was often a chain of redirects—one or two domains outside the parking company—before threat arrives," Brunsdon stated. "Each time in the handoff the device is profiled again and again, before being passed off to a malicious domain or else a decoy page like Amazon.com or Alibaba.com if they decide it’s not worth targeting."

Brunsdon also pointed out that while domain parking services claim their search results are relevant to the parked domains, Infoblox’s testing found that almost none of the displayed content bore any relation to the lookalike domain names.

Another concerning discovery by Infoblox involves the domain "domaincntrol[.]com," which differs from GoDaddy’s name servers by a single character. This domain has historically exploited typos in DNS configurations to redirect users to malicious websites. However, recent observations indicate a more targeted approach: malicious redirects now only occur when queries for the misconfigured domain originate from visitors using Cloudflare’s DNS resolvers (1.1.1.1). All other visitors are presented with a page that refuses to load.

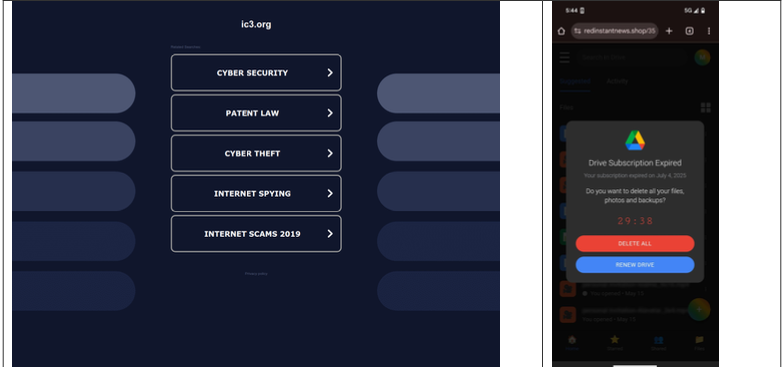

The Infoblox report also underscores the vulnerability of government domains. Researchers found that variations of well-known government domains are being targeted by malicious ad networks. In one instance, a researcher attempting to report a crime to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) accidentally visited "ic3[.]org" instead of the correct "ic3[.]gov." Their device was promptly redirected to a fake "Drive Subscription Expired" page. While this particular incident resulted in a scam, the researchers noted that users could just as easily be subjected to information-stealing malware or trojans.

Crucially, the malicious activity identified by Infoblox is not attributed to any single known entity. The report explicitly states that the domain parking or advertising platforms mentioned in the study were not directly implicated in the malvertising campaigns documented. However, Infoblox concluded that despite claims by parking companies to work only with reputable advertisers, the traffic directed to these malicious domains was frequently resold through affiliate networks. This multi-layered reselling often meant that the final advertiser had no direct business relationship with the original parking companies, obscuring accountability.

Adding another layer of concern, Infoblox highlighted that recent policy adjustments by Google may have inadvertently amplified the risks associated with direct search abuse. Brunsdon explained that while Google AdSense previously allowed ads to be placed on parked pages by default, a policy change implemented in early 2025 requires advertisers to actively opt-in to display their ads on parked domains. This shift, while seemingly aimed at protecting users, could have unintended consequences by making the monetization of malicious parked domains more challenging for legitimate advertisers, potentially pushing them towards less scrupulous channels. The report implies that this change, while well-intentioned, might not fully address the underlying problem of malicious redirection from parked domains.