The journey towards this groundbreaking achievement began with a deep understanding of the fundamental differences between classical and quantum computing. Conventional computers, the workhorses of our digital age, rely on bits, which exist in one of two discrete states: 0 or 1. This binary system, while robust, fundamentally limits the complexity of problems these machines can tackle. Quantum computers, on the other hand, harness the peculiar principles of quantum mechanics, employing quantum bits, or qubits. Unlike classical bits, qubits can exist in a superposition of states, meaning they can simultaneously represent 0, 1, and an infinite number of possibilities in between. This ability to exist in multiple states at once is the key to quantum computing’s immense potential. A quantum computer with just 20 qubits, for instance, can represent over a million different states simultaneously. This phenomenon, superposition, is what empowers quantum computers to tackle extraordinarily complex problems that lie far beyond the reach of even the most powerful conventional supercomputers, opening up new frontiers in fields such as drug discovery, materials science, financial modeling, artificial intelligence, and secure encryption.

However, unlocking the computational prowess of qubits is not without its challenges. To translate the quantum computations into usable information, the fragile quantum states of the qubits must be measured and converted into classical signals. This delicate process necessitates the use of extremely sensitive microwave amplifiers. These amplifiers must be capable of accurately detecting and amplifying the incredibly weak signals emanating from the qubits. The very act of reading quantum information is akin to tiptoeing through a minefield of potential disturbances. Even the slightest thermal fluctuation, ambient noise, or stray electromagnetic interference can disrupt the delicate quantum state of a qubit, a phenomenon known as decoherence. When decoherence occurs, the qubit loses its quantum integrity, rendering the information it holds unusable. Furthermore, conventional amplifiers, in their operation, generate heat as a byproduct. This generated heat further exacerbates the problem of decoherence, creating a detrimental feedback loop. Consequently, the pursuit of more efficient and less heat-generating qubit amplifiers has been a persistent and critical area of research within the quantum computing community. The recent breakthrough from Chalmers University of Technology represents a significant stride in overcoming this fundamental hurdle.

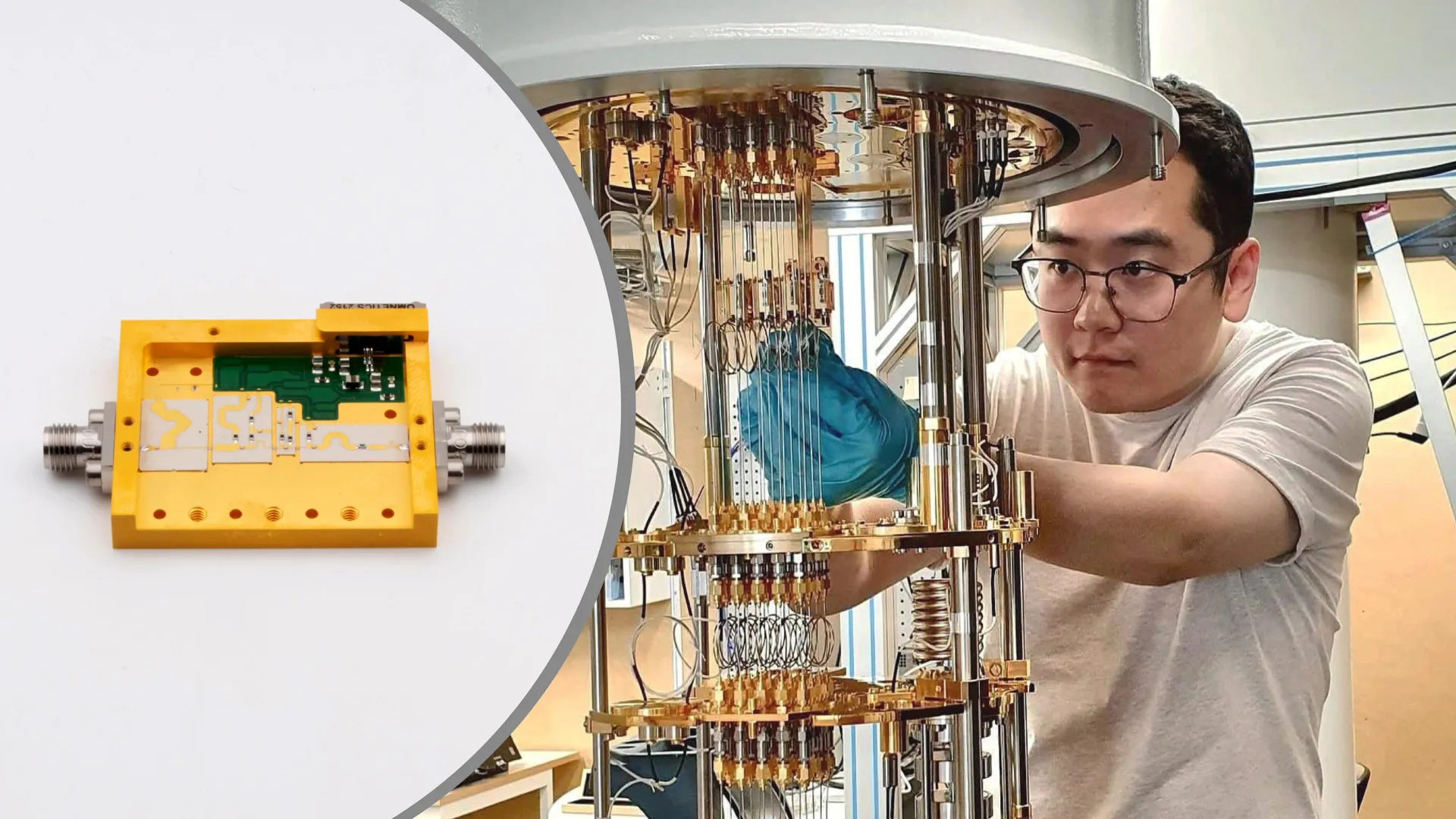

Yin Zeng, a doctoral student in terahertz and millimeter wave technology at Chalmers and the lead author of the study, expressed his enthusiasm. "This is the most sensitive amplifier that can be built today using transistors," he stated. "We’ve now managed to reduce its power consumption to just one-tenth of that required by today’s best amplifiers – without compromising performance. We hope and believe that this breakthrough will enable more accurate readout of qubits in the future." The study, published in the prestigious journal IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, details the innovative design principles that led to this remarkable efficiency gain.

This advancement holds profound implications for the scaling up of quantum computers. The ultimate goal of quantum computing research is to build machines with a vast number of qubits, thereby exponentially increasing their computational power and capacity for tackling increasingly complex problems. Chalmers University has been a leading force in this endeavor, actively contributing to this field through initiatives like the Wallenberg Centre for Quantum Technology. As the number of qubits in a quantum computer increases, so too does its potential for groundbreaking discoveries. However, this scaling also presents a significant challenge: larger quantum systems require a greater number of amplifiers, leading to a proportional increase in overall power consumption. This escalating power demand, in turn, amplifies the problem of heat generation and qubit decoherence.

Professor Jan Grahn, a leading figure in microwave electronics at Chalmers and Yin Zeng’s principal supervisor, underscored the importance of this development. "This study offers a solution in future upscaling of quantum computers where the heat generated by these qubit amplifiers poses a major limiting factor," he explained. The core innovation lies in the amplifier’s operational mode. Unlike traditional low-noise amplifiers that are continuously powered on, the new amplifier developed by the Chalmers researchers is pulse-operated. This means it is activated only when it is actively needed for amplifying qubit signals, rather than being constantly engaged.

"This is the first demonstration of low-noise semiconductor amplifiers for quantum readout in pulsed operation that does not affect performance and with drastically reduced power consumption compared to the current state of the art," Professor Grahn emphasized. The challenge in implementing a pulse-operated amplifier for quantum readout is ensuring that it can respond quickly enough to the fleeting nature of quantum information. Quantum information is transmitted in short pulses, and any delay in amplification would result in lost data. The Chalmers team ingeniously addressed this by incorporating a smart algorithm into the amplifier’s design. This intelligent control mechanism allows the amplifier to activate and respond to incoming qubit pulses with unprecedented speed.

To rigorously validate their approach, the researchers also developed a novel measurement technique specifically designed for assessing the noise and amplification characteristics of pulse-operated low-noise microwave amplifiers. This new methodology was crucial in confirming the amplifier’s exceptional performance. "We used genetic programming to enable smart control of the amplifier," said Yin Zeng. "As a result, it responded much faster to the incoming qubit pulse, in just 35 nanoseconds." This rapid response time is critical for ensuring accurate and complete readout of quantum information.

The research paper, titled "Pulsed HEMT LNA Operation for Qubit Readout," details the technical specifications and experimental results of this groundbreaking invention. The study was authored by Yin Zeng and Jan Grahn from the Terahertz and Millimeter Wave Technology Laboratory at Chalmers University of Technology, alongside Jörgen Stenarson and Peter Sobis from Low Noise Factory AB. The development of this advanced amplifier was made possible through the collaborative efforts at the Kollberg Laboratory at Chalmers University of Technology and Low Noise Factory AB, located in Gothenburg, Sweden. This significant advancement was supported by funding from the Chalmers Centre for Wireless Infrastructure Technology (WiTECH) and the Vinnova program "Smarter electronic systems," highlighting the collaborative and well-supported nature of this pioneering research. The implications of this more efficient and responsive amplifier are far-reaching, promising to accelerate the journey towards building practical and powerful quantum computers capable of revolutionizing scientific discovery and technological innovation.