"These nanohelices achieve spin polarization exceeding ~80% — just by their geometry and magnetism," stated Professor Young Keun Kim of Korea University, a co-corresponding author of the study, underscoring the profound implications of their discovery. He further emphasized the rarity and significance of their findings: "This is a rare combination of structural chirality and intrinsic ferromagnetism, enabling spin filtering at room temperature without complex magnetic circuitry or cryogenics, and provides a new way to engineer electron behavior using structural design." This elegant integration of geometric form and magnetic property eliminates the need for cumbersome and energy-intensive cooling or intricate magnetic setups, paving the way for more practical and widespread spintronic applications.

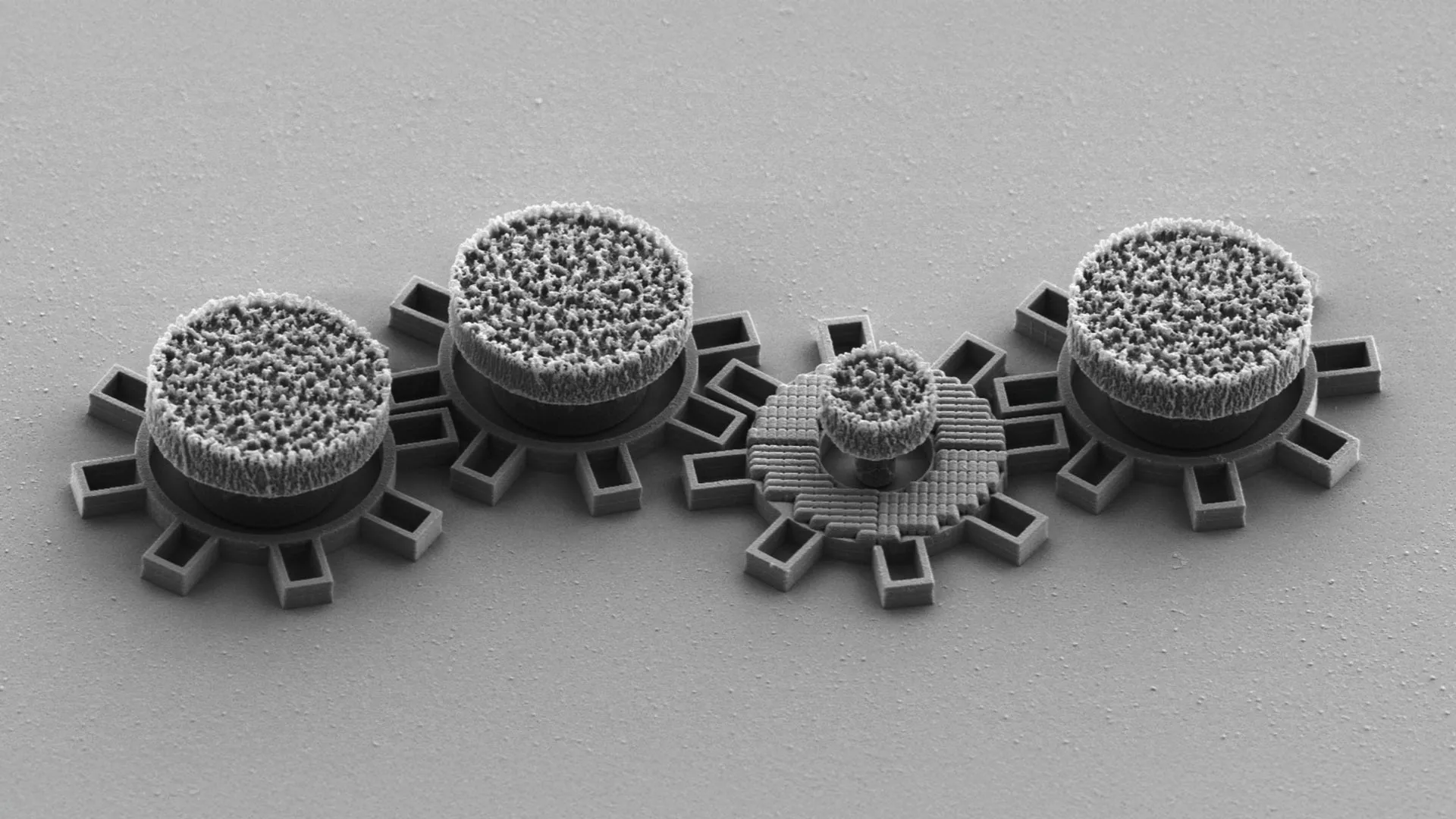

The research team’s success stems from their innovative approach to fabricating left- and right-handed chiral magnetic nanohelices. They achieved this by precisely controlling the electrochemical metal crystallization process. A pivotal aspect of their innovation involved the introduction of trace amounts of specific chiral organic molecules, such as cinchonine or cinchonidine. These molecules acted as templates, guiding the formation of helices with a meticulously defined handedness – a feat that has historically proven exceedingly difficult to achieve in inorganic systems. The researchers then experimentally validated the spin-controlling capabilities of these nanohelices. They demonstrated that when a nanohelix exhibits a right-handed twist, it preferentially permits electrons with one specific spin direction to pass through, while effectively blocking electrons with the opposite spin. This experimental confirmation represents the discovery of a three-dimensional inorganic helical nanostructure with the remarkable ability to control electron spin, a significant advancement in materials science.

Professor Ki Tae Nam of Seoul National University, another co-corresponding author, highlighted the broader impact of their work, drawing parallels to established principles in organic chemistry: "Chirality is well-understood in organic molecules, where the handedness of a structure often determines its biological or chemical function." He then elaborated on the distinct challenges faced in inorganic materials: "But in metals and inorganic materials, controlling chirality during synthesis is extremely difficult, especially at the nanoscale. The fact that we could program the direction of inorganic helices simply by adding chiral molecules is a breakthrough in materials chemistry." This ability to imbue inorganic nanostructures with controllable chirality opens up entirely new avenues for designing functional materials with tailored properties.

To rigorously confirm the chirality of the fabricated nanohelices, the researchers devised an ingenious electromotive force (emf)-based chirality evaluation method. This novel technique allowed them to measure the emf generated by the helices when subjected to rotating magnetic fields. The results were clear and compelling: left-handed and right-handed helices produced distinct, opposite emf signals. This quantitative verification of chirality is particularly valuable as it works even for materials that do not exhibit strong interactions with light, a common limitation in other chirality characterization methods. This robust validation process adds significant credibility to their findings and the reliability of their nanohelical structures.

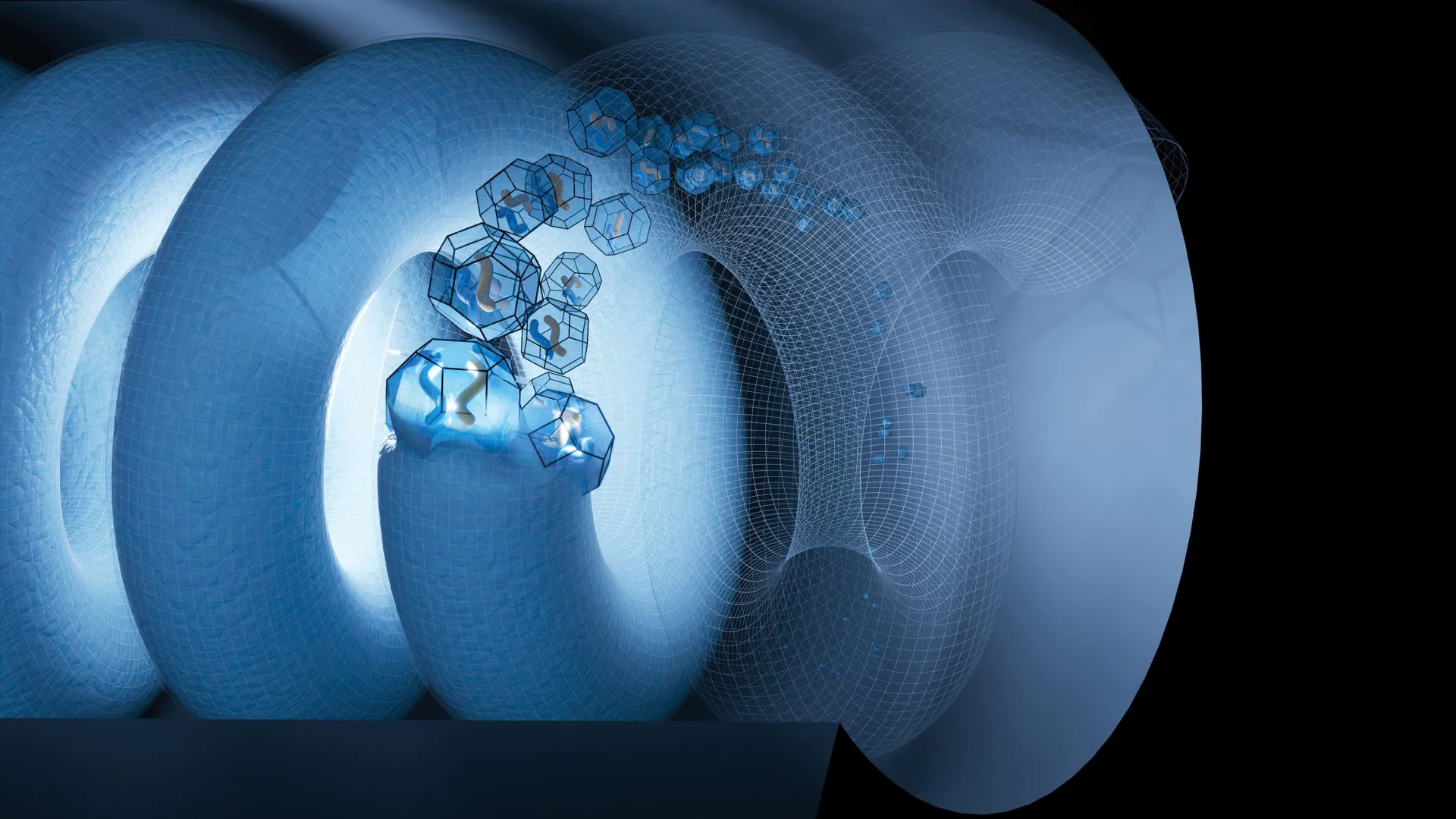

Further investigation by the research team revealed another crucial property of these magnetic nanohelices: the magnetic material itself, through its inherent magnetization and ordered spin alignment, facilitates long-distance spin transport at room temperature. This remarkable effect is sustained by strong exchange energy within the material, ensuring consistent performance regardless of the orientation between the chiral axis and the direction of spin injection. Crucially, this spin transport phenomenon was not observed in non-magnetic nanohelices of comparable size, underscoring the unique contribution of the magnetic nature of their helices. This marks the first reported measurement of asymmetric spin transport in a relatively macroscopic chiral body, demonstrating the practical implications of their nanoscale engineering. To bridge the gap between fundamental research and real-world applications, the team also successfully developed a solid-state device that exhibited chirality-dependent conduction signals. This tangible demonstration provides a clear pathway toward the practical implementation of these nanohelices in future spintronic devices.

Professor Kim expressed his optimism about the future potential of this technology, stating, "We believe this system could become a platform for chiral spintronics and architecture of chiral magnetic nanostructures." This pioneering work represents a powerful synergy between geometry, magnetism, and spin transport, all achieved using scalable and readily available inorganic materials. The versatility of their electrochemical fabrication method allows for precise control over the handedness (left or right) of the helices, and even the potential to create structures with multiple strands, such as double or more complex helices. This remarkable tunability is expected to be a significant driver for the development of novel applications across a wide spectrum of technological fields, heralding a new era in the design and engineering of advanced electronic materials. The ability to manipulate electron spin through the precise geometric and magnetic design of nanoscale structures like these magnetic nanohelices is poised to revolutionize the way we store, process, and transmit information, ushering in an age of faster, more efficient, and more powerful electronic devices.