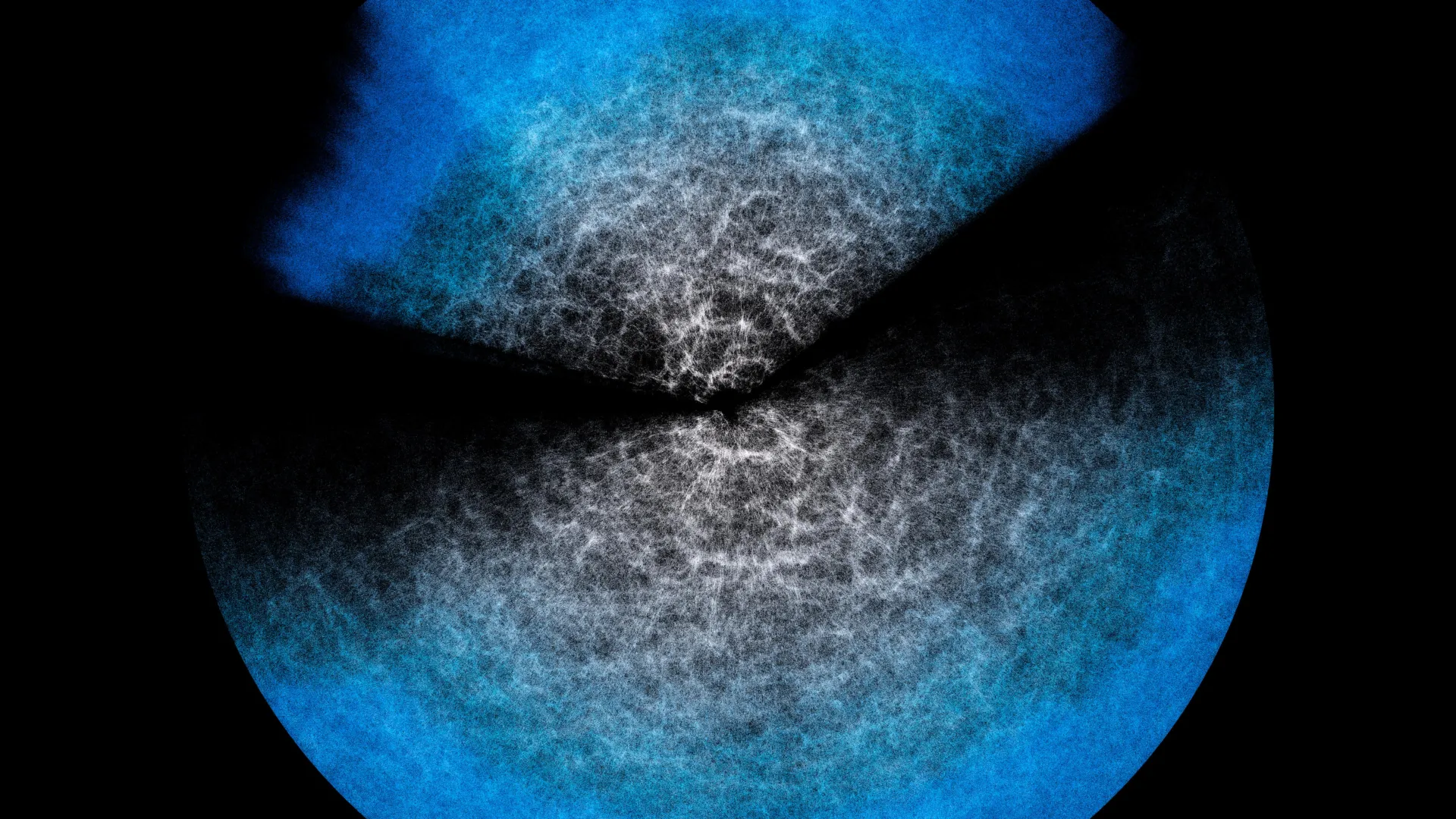

The sheer immensity of the Universe can be a dizzying concept. Imagine a galaxy, a swirling island of stars and cosmic dust, appearing as a mere speck against the backdrop of the cosmos. This speck, along with countless others, coalesces into vast clusters, which in turn bind together to form even grander superclusters. These colossal structures are not scattered randomly but are intricately woven into an immense three-dimensional tapestry, forming filaments that are punctuated by vast, empty voids – the very skeleton of our Universe. This mind-boggling scale, capable of inducing vertigo, naturally raises questions about how humanity can possibly comprehend, let alone "see," such an unfathomable expanse. The answer lies in a sophisticated interplay of scientific ingenuity. Astronomers and cosmologists meticulously combine the fundamental laws of physics governing the Universe with precise data meticulously gathered by astronomical instruments. From this rich foundation, they construct theoretical models, such as the highly influential Effective Field Theory of Large-Scale Structure (EFTofLSS). When these models are "fed" with observational data, they embark on a statistical description of the cosmic web, enabling scientists to estimate its key parameters and unravel its underlying architecture.

However, the pursuit of understanding this cosmic web through models like EFTofLSS comes with a significant demand for computational resources and time. As the volume of astronomical datasets at our disposal grows at an exponential rate, driven by increasingly powerful telescopes and ambitious sky surveys, the need for efficient and agile analytical methods becomes paramount. Scientists are constantly seeking ways to streamline these complex analyses without compromising on precision. This is where the concept of "emulators" emerges as a crucial innovation. Emulators are designed to "imitate" the behavior of these complex physics models, but they achieve this imitation at a vastly accelerated pace, significantly reducing the computational burden.

The inherent question that arises with any "shortcut" in scientific computation is the potential for a loss of accuracy. To address this critical concern, an international team of researchers, comprising esteemed institutions such as the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) in Italy, the University of Parma in Italy, and the University of Waterloo in Canada, has published a groundbreaking study in the esteemed Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (JCAP). Their research rigorously tests an emulator they developed, named Effort.jl. The findings are nothing short of revolutionary: Effort.jl demonstrates that it delivers essentially the same level of correctness as the complex model it imitates. In some instances, it even manages to capture finer details that might be challenging to extract with the original model under time constraints. Crucially, this remarkable feat is achieved while running in mere minutes on a standard laptop, a stark contrast to the days or weeks typically required on a supercomputer.

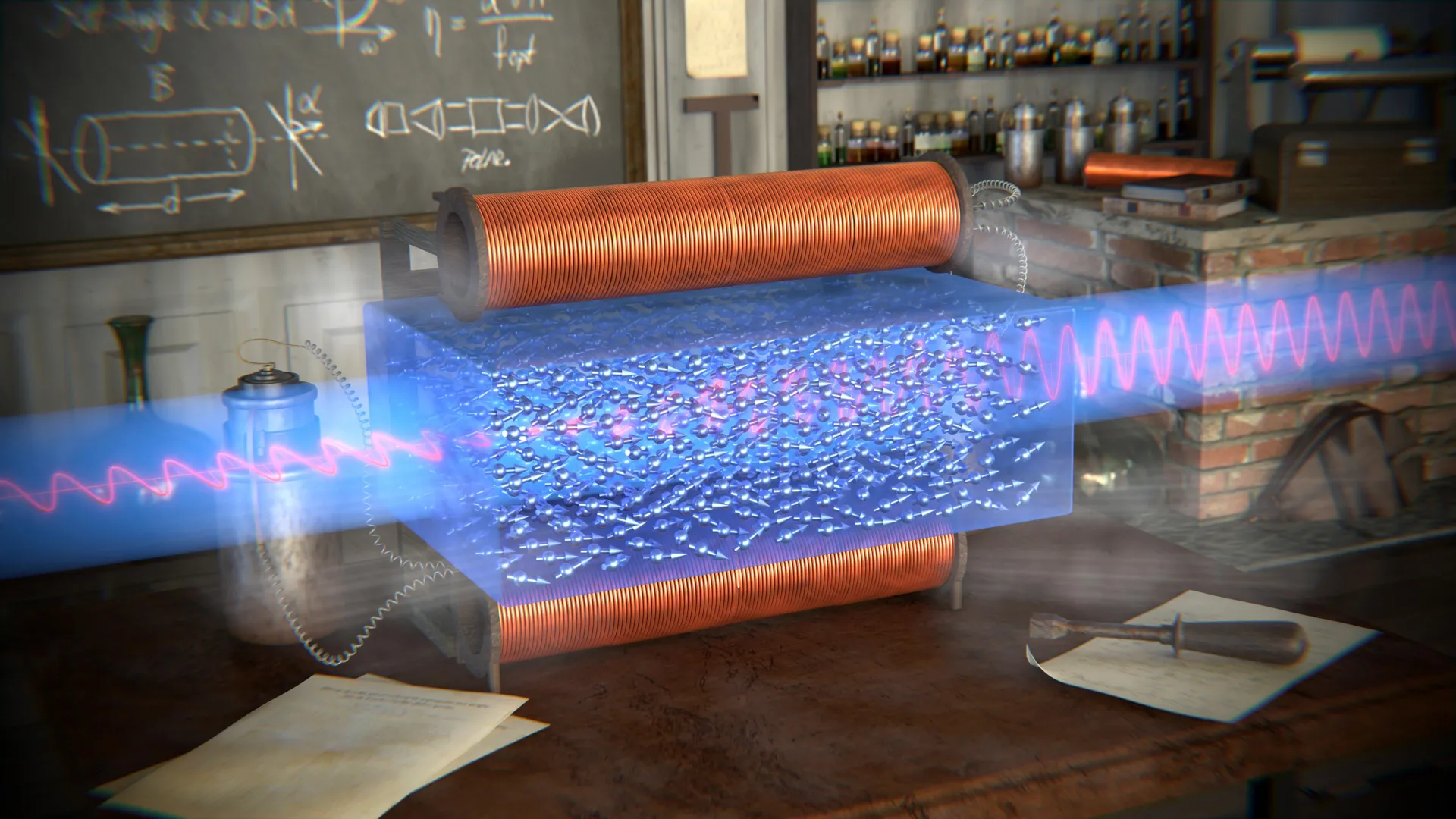

Marco Bonici, a researcher at the University of Waterloo and the lead author of the study, eloquently illustrates the principle behind these advanced models. "Imagine wanting to study the contents of a glass of water at the level of its microscopic components, the individual atoms, or even smaller: in theory you can," Bonici explains. "But if we wanted to describe in detail what happens when the water moves, the explosive growth of the required calculations makes it practically impossible. However, you can encode certain properties at the microscopic level and see their effect at the macroscopic level, namely the movement of the fluid in the glass. This is what an effective field theory does, that is, a model like EFTofLSS, where the water in my example is the Universe on very large scales and the microscopic components are small-scale physical processes." This analogy effectively conveys how EFTofLSS distills complex, small-scale physics into a statistically manageable framework for understanding the large-scale cosmic structure.

The theoretical model, in essence, provides a statistical explanation for the observed structure that gives rise to the collected data. Astronomical observations are fed into the code, which then computes a "prediction" of the Universe’s large-scale structure. However, as Bonici highlights, this process is computationally intensive, demanding significant time and substantial computing power. Given the ever-increasing volume of data being generated by current and upcoming astronomical surveys – such as the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), which has already begun releasing its initial findings, and the European Space Agency’s Euclid mission, poised to deliver unprecedented insights – performing these exhaustive computations for every analysis is simply not practical.

"This is why we now turn to emulators like ours, which can drastically cut time and resources," Bonici continues, emphasizing the practical necessity of such tools. An emulator operates by mimicking the output of the original model. Its core functionality is often powered by a sophisticated neural network. This neural network is trained to learn the intricate relationship between input parameters and the already-computed predictions of the physics model. By being trained on a diverse set of the model’s outputs, the neural network gains the ability to generalize and predict the model’s response for new combinations of parameters that it may not have encountered during training. It’s important to understand that the emulator doesn’t "understand" the underlying physics in the same way a human scientist does. Instead, it develops a profound understanding of the theoretical model’s behavior and can accurately anticipate its output for novel inputs.

The true innovation of Effort.jl lies in its novel approach to further optimize the training phase. It achieves this by ingeniously embedding existing knowledge about how predictions change when parameters are subtly altered directly into the algorithm. Rather than forcing the neural network to "re-learn" these fundamental relationships, Effort.jl leverages them from the outset. Furthermore, Effort.jl employs the use of gradients. Gradients essentially quantify "how much and in which direction" the predictions of the model change if a specific parameter is tweaked by a minuscule amount. This incorporation of gradient information acts as a powerful catalyst, enabling the emulator to learn effectively from significantly fewer examples. This reduction in the learning burden directly translates to lower computational needs, allowing the emulator to operate efficiently on less powerful hardware, such as a standard laptop.

The scientific community rightly demands rigorous validation for any tool that offers such a significant computational shortcut. If an emulator doesn’t inherently "know" the physics, how can we be certain that its accelerated predictions are indeed correct and align with the results the full physics model would produce? The newly published study directly addresses this crucial question. It meticulously demonstrates that Effort.jl’s accuracy, when tested against both simulated data and real astronomical observations, exhibits close agreement with the predictions of the EFTofLSS model. "And in some cases," Bonici proudly concludes, "where with the model you have to trim part of the analysis to speed things up, with Effort.jl we were able to include those missing pieces as well." This highlights an additional benefit: Effort.jl not only matches the model’s accuracy but can, in certain scenarios, enable a more complete analysis that might otherwise be computationally prohibitive. Consequently, Effort.jl emerges as an invaluable ally for cosmologists and astrophysicists, poised to play a pivotal role in analyzing the torrent of upcoming data from groundbreaking experiments like DESI and Euclid. These missions promise to dramatically expand our knowledge of the Universe’s large-scale structure and its evolutionary history.

The seminal study, titled "Effort.jl: a fast and differentiable emulator for the Effective Field Theory of the Large Scale Structure of the Universe," authored by Marco Bonici, Guido D’Amico, Julien Bel, and Carmelita Carbone, is readily accessible to the scientific community within the pages of the Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (JCAP), marking a significant advancement in the field of computational cosmology.