Most of us rarely question the accuracy of the GPS dot that shows our location on a map. Yet, when navigating a new urban landscape with our smartphones, that familiar digital pointer can inexplicably jump and stutter, creating a disorienting experience of seemingly teleporting along a steady sidewalk. This frustrating inaccuracy, a common ailment for satellite navigation systems, is particularly pronounced in the complex environments of cities. Ardeshir Mohamadi, a doctoral fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), has been at the forefront of research aimed at rectifying this very issue. His work focuses on developing significantly more precise and affordable GPS receivers, akin to those found in our everyday smartphones and fitness trackers, without the reliance on costly external correction services. The urgency for such high accuracy is amplified by the burgeoning field of autonomous vehicles, where even a slight positional error can have critical safety implications.

The primary culprit behind GPS unreliability in urban settings is the phenomenon known as "urban canyons." This descriptive term refers to the environment created by tall buildings, dense construction, and the prevalence of reflective surfaces like glass and concrete. "Cities are brutal for satellite navigation," Mohamadi explains, elaborating that "glass and concrete make satellite signals bounce back and forth. Tall buildings block the view, and what works perfectly on an open motorway is not so good when you enter a built-up area." This signal reflection is the core problem. When GPS signals bounce off buildings, they travel a longer, more circuitous path to reach the receiver. This increased travel time leads to a miscalculation of the distance between the receiver and the orbiting satellites, resulting in an inaccurate positional fix. Imagine standing at the bottom of a deep gorge; signals only reach you after multiple reflections off the canyon walls. This is precisely the challenge faced by GPS receivers trapped within cityscapes.

For autonomous vehicles, the consequences of this navigational uncertainty are stark. "For autonomous vehicles, this makes the difference between confident, safe behavior and hesitant, unreliable driving," Mohamadi emphasizes. It is this critical distinction that drove the development of "SmartNav," a novel positioning technology specifically engineered to thrive within these challenging "urban canyons."

The problem, however, is not solely confined to signal disruption. Even the signals that do reach the receiver directly, without significant reflection, often lack the inherent precision required for pinpoint accuracy. To address this multi-faceted challenge, Mohamadi and his team at NTNU have devised an innovative system that ingeniously combines several different technologies. The fruit of their labor is a sophisticated computer program designed for seamless integration into the navigation systems of autonomous vehicles. Before delving further into their solution, it’s beneficial to briefly revisit the fundamental principles of GPS.

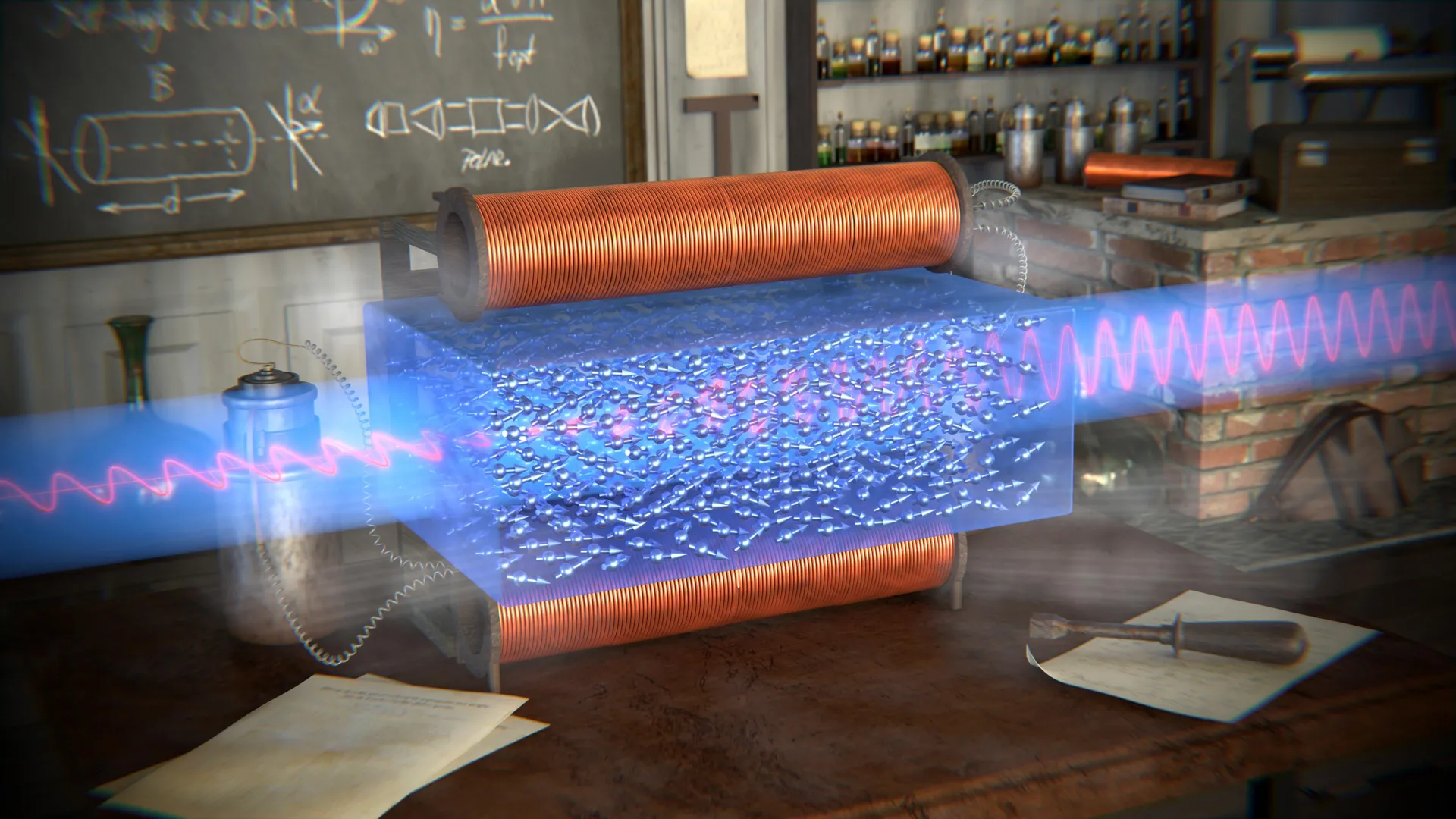

The Global Positioning System (GPS) relies on a constellation of satellites orbiting Earth, continuously transmitting radio wave signals. A GPS receiver, such as the one in your phone, picks up these signals. By receiving signals from at least four satellites, the receiver can triangulate its position on Earth. Each signal is essentially a tiny message containing the satellite’s precise location and the exact time the signal was sent – a timestamp from space.

The core of the urban GPS dilemma lies in the integrity of this timestamp. When signals bounce off buildings, the recorded transmission time becomes distorted, leading to erroneous distance calculations and, consequently, an inaccurate location. One of the initial avenues explored by the NTNU researchers was to bypass this problematic timestamp altogether. Their idea was to instead leverage information directly from the radio wave itself, specifically its "carrier phase." The carrier phase refers to the direction of the wave – whether it’s traveling upwards or downwards as it reaches the receiver. "Using only the carrier phase can provide very high accuracy," Mohamadi notes, "but it takes time, which is not very practical when the receiver is moving." The limitation here is significant: to achieve a sufficiently accurate reading using solely the carrier phase, the receiver would need to remain stationary for several minutes, a duration entirely impractical for a moving vehicle or a person on the go.

Fortunately, there are other established methods for enhancing GPS signal accuracy. One such technique involves utilizing a network of ground-based reference stations known as RTK (Real Time Kinematics). These stations provide correction data to the GPS receiver, significantly improving its precision. However, RTK systems are typically expensive and primarily intended for professional applications, requiring users to be within a certain proximity to these base stations.

A more advanced alternative is PPP-RTK (Precise Point Positioning – Real-Time Kinematic). This approach merges the benefits of precise positioning with satellite-based correction signals. The European Galileo system has notably embraced this technology by offering its correction data free of charge, making it more accessible. Yet, even with these advancements, the ultimate solution for urban navigation remained elusive.

The breakthrough arrived with an unexpected collaborator: Google. While the Trondheim-based researchers were diligently refining their algorithms, Google independently launched a groundbreaking service for its Android users. This service leverages vast datasets of 3D building models for nearly 4,000 cities worldwide. Imagine planning a trip to London; with Google Maps, you can not only see the street layout but also meticulously examine the 3D representations of buildings, their heights, and facades. Google is now employing these detailed 3D models to predict how satellite signals will interact with the urban environment, specifically how they will reflect off buildings. This predictive capability is a crucial step in overcoming the "wrong-side-of-the-street" problem, where GPS inaccuracies can lead users to believe they are on the opposite side of the road from their actual location.

"They combine data from sensors, Wi-Fi, mobile networks and 3D building models to produce smooth position estimates that can withstand errors caused by reflections," Mohamadi explains, highlighting the power of this integrated approach.

The NTNU researchers seized this opportunity to weave Google’s innovative 3D modeling capabilities into their own sophisticated algorithms. By combining all these disparate correction systems – the carrier phase information, PPP-RTK, and Google’s predictive 3D urban models – with their proprietary algorithms, they achieved a remarkable feat. When tested on the streets of Trondheim, their integrated system delivered an accuracy that surpassed ten centimeters 90 percent of the time. This level of precision is a game-changer for urban navigation, offering reliability that was previously unattainable.

The researchers are optimistic about the widespread adoption of their technology. The integration of PPP-RTK, in particular, is poised to make this enhanced GPS accuracy accessible to the general public. "PPP-RTK reduces the need for dense networks of local base stations and expensive subscriptions, enabling cheap, large-scale implementation on mass-market receivers," Mohamadi concludes. This signifies a future where navigating bustling cityscapes, whether on foot, by car, or in an autonomous vehicle, will be a seamless and precise experience, free from the frustrations of unreliable GPS signals.