A pivotal recent study, originating from the esteemed Swinburne University, has stepped forward to address this crucial dilemma, offering a tangible solution to a problem that has been a significant bottleneck in the field. The core of the challenge, as articulated by lead author Alexander Dellios, a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Swinburne’s Centre for Quantum Science and Technology Theory, lies in the very nature of quantum computation. "There exists a range of problems that even the world’s fastest supercomputer cannot solve, unless one is willing to wait millions, or even billions, of years for an answer," Dellios explains. This stark reality underscores the urgent need for innovative verification strategies. "Therefore, in order to validate quantum computers, methods are needed to compare theory and result without waiting years for a supercomputer to perform the same task."

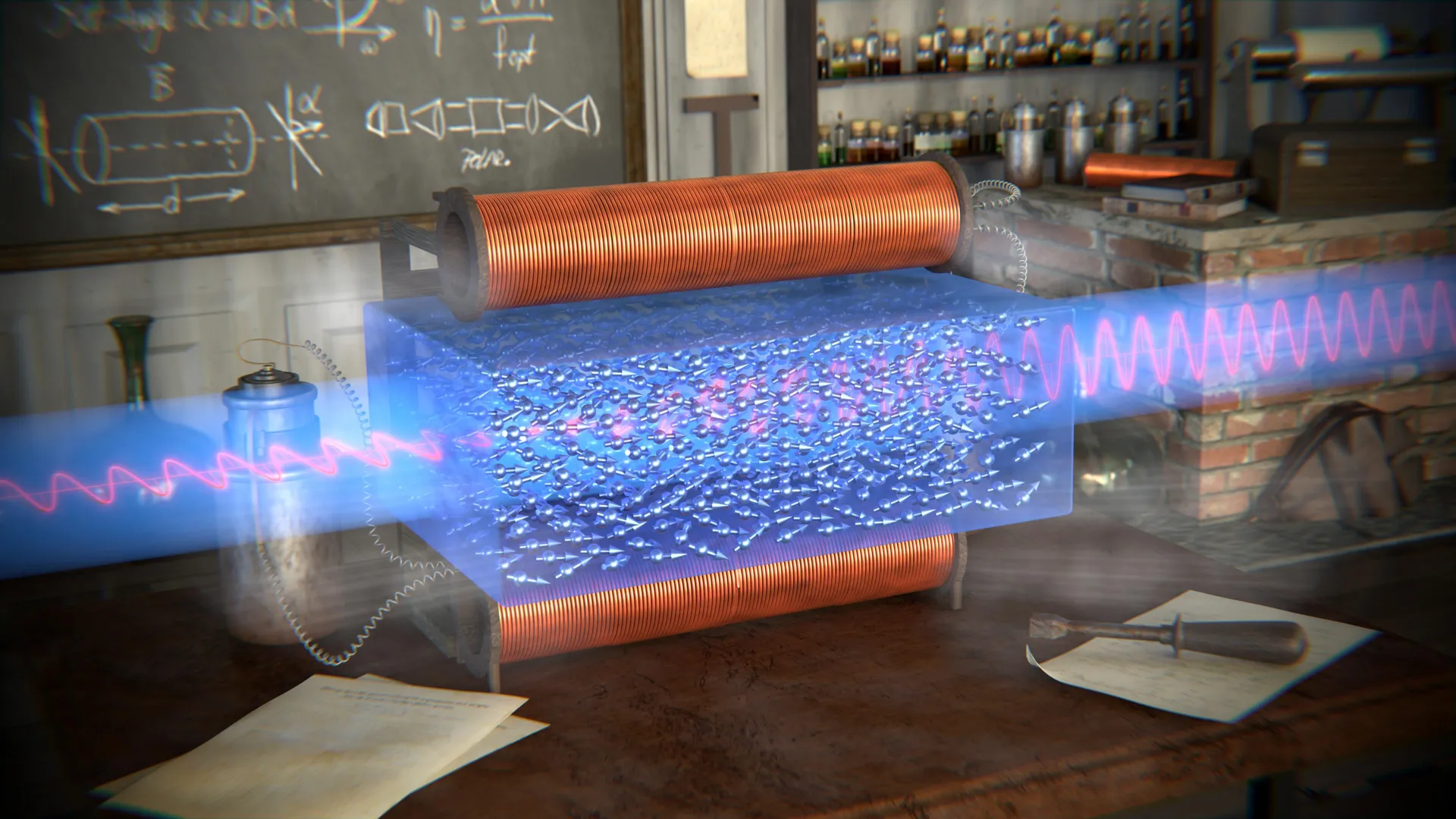

The Swinburne research team has meticulously developed novel techniques specifically designed to ascertain the accuracy of a particular class of quantum devices: Gaussian Boson Samplers (GBS). These sophisticated GBS machines harness the peculiar properties of photons, the fundamental particles of light, to perform intricate probability calculations. The sheer complexity of these calculations means that even the most advanced classical supercomputers would require thousands of years to replicate them. This immense disparity in computational power is precisely why traditional verification methods are rendered impractical, necessitating the development of entirely new approaches.

The newly devised tools offer a remarkable leap forward in efficiency and accuracy. "In just a few minutes on a laptop, the methods developed allow us to determine whether a GBS experiment is outputting the correct answer and what errors, if any, are present," states Dellios, highlighting the astonishing speed and accessibility of their breakthrough. This capability transforms the verification process from a daunting, time-prohibitive endeavor into a routine, almost instantaneous, diagnostic.

To rigorously test and demonstrate the efficacy of their innovative approach, the researchers applied it to a recently published GBS experiment. This particular experiment, due to its inherent complexity, would have demanded at least 9,000 years to reproduce using the most powerful supercomputers currently available. The analysis performed by Dellios and his team, however, took mere minutes on a standard laptop. Their meticulous examination revealed a critical discrepancy: the resulting probability distribution generated by the experiment did not align with the intended theoretical target. Furthermore, their analysis unearthed previously undetected “extra noise” within the experiment, a subtle but significant imperfection that had gone unnoticed in prior evaluations. This finding is of paramount importance as it directly impacts the reliability and accuracy of the quantum computation.

The implications of this discovery are far-reaching. The next critical step for the researchers is to investigate whether the observed unexpected distribution is, in itself, a computationally difficult problem to reproduce, or if the identified errors are the direct cause of the device losing its crucial "quantumness." The concept of "quantumness" refers to the unique quantum mechanical properties, such as superposition and entanglement, that give quantum computers their extraordinary power. If errors degrade this quantumness, it fundamentally compromises the integrity of the computation and the validity of its results. Understanding this relationship is vital for developing strategies to mitigate such errors and preserve the computational advantage offered by quantum mechanics.

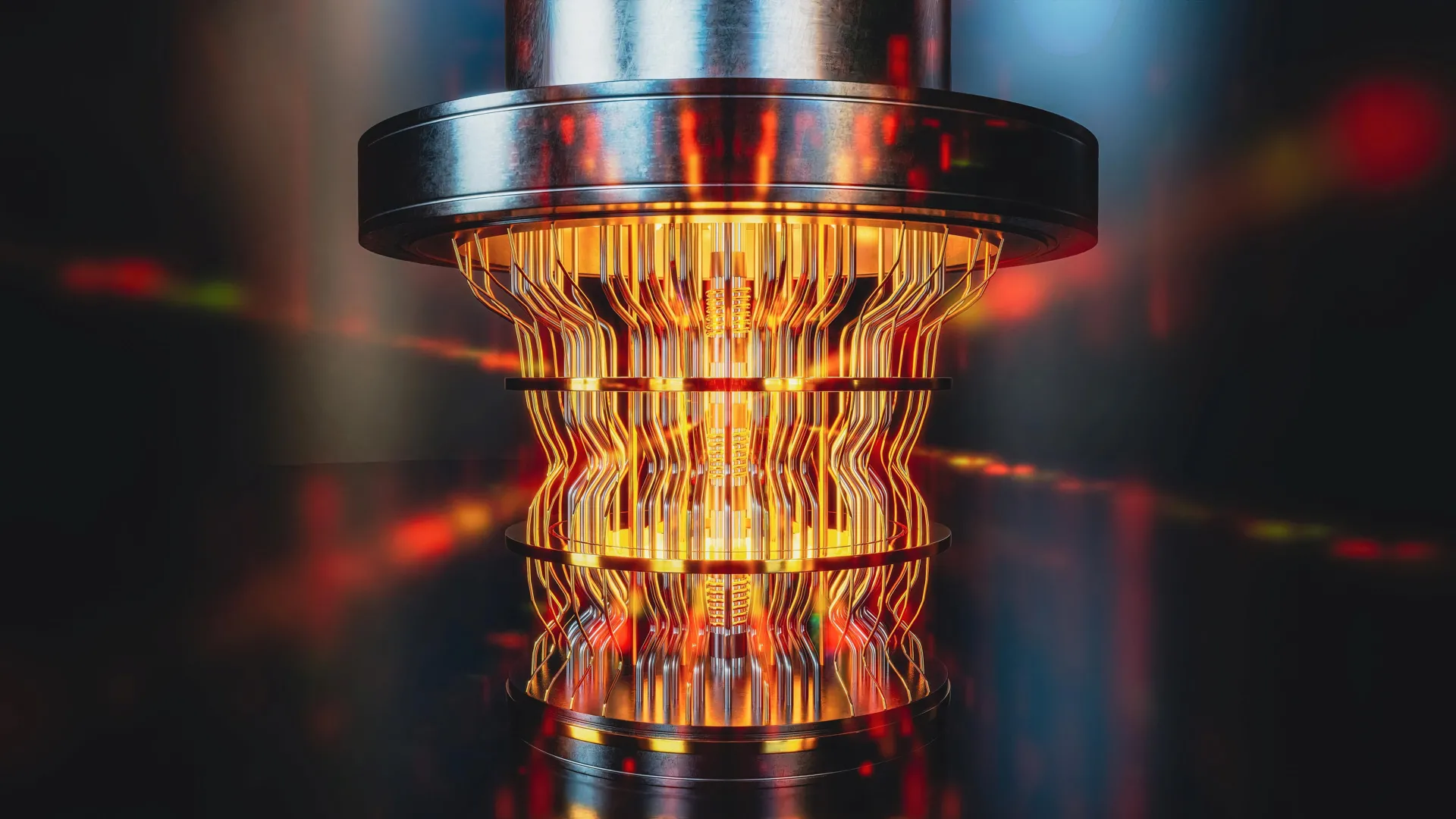

The successful outcome of this investigation is poised to significantly influence the trajectory of quantum computer development, particularly in the pursuit of large-scale, error-free machines that are suitable for widespread commercial adoption. This is a goal that Dellios expresses a strong commitment to championing. "Developing large-scale, error-free quantum computers is a herculean task that, if achieved, will revolutionize fields such as drug development, AI, cyber security, and allow us to deepen our understanding of the physical universe," he asserts, painting a vivid picture of the transformative impact of this technology.

Dellios further emphasizes the indispensable role of scalable validation methods in this grand endeavor. "A vital component of this task is scalable methods of validating quantum computers, which increase our understanding of what errors are affecting these systems and how to correct for them, ensuring they retain their ‘quantumness’." This sentiment underscores that the journey towards functional quantum computers is not merely about building them, but about building them reliably and verifiably. The ability to quickly and accurately identify and correct errors is as crucial as the development of the quantum hardware itself.

The research from Swinburne University provides a tangible and efficient pathway to address the validation challenge. By enabling rapid assessment of GBS experiments, their methods allow scientists to iterate more quickly on hardware designs and error correction protocols. This accelerated feedback loop is essential for navigating the complex landscape of quantum system development. Imagine the painstaking process of waiting years for a supercomputer to verify an experiment, only to find it flawed. Dellios’s team has effectively compressed that timeline from years to minutes, dramatically accelerating the pace of innovation.

The identification of unexpected noise in the experimental results is also a critical insight. It suggests that even when aiming for specific quantum computations, external factors or intrinsic imperfections in the quantum hardware can introduce deviations. Understanding the nature and source of this noise is key to developing more robust quantum systems. This could involve improving the quality of the photons used, enhancing the precision of the optical components, or implementing more sophisticated error-correction codes that are specifically designed to combat these types of deviations.

The broader implications of this work extend beyond GBS devices. While the current study focuses on this specific type of quantum computer, the underlying principles of developing efficient verification techniques are likely transferable to other quantum computing architectures, such as superconducting qubits or trapped ions. The fundamental challenge of verifying complex quantum calculations remains a universal hurdle. Therefore, the methodologies pioneered by the Swinburne team could serve as a foundational blueprint for developing verification tools across the diverse landscape of emerging quantum technologies.

In conclusion, the scientific community has taken a significant stride forward with the development of these novel verification techniques. This breakthrough not only addresses a critical impediment to the progress of quantum computing but also paves the way for the realization of its immense, world-changing potential. The ability to confidently confirm the accuracy of quantum computations is an essential prerequisite for building trust in these nascent technologies and for unlocking their transformative capabilities in fields that will shape the future of humanity. The race is on, and with tools like these, the finish line for reliable, commercially viable quantum computers appears closer than ever before.