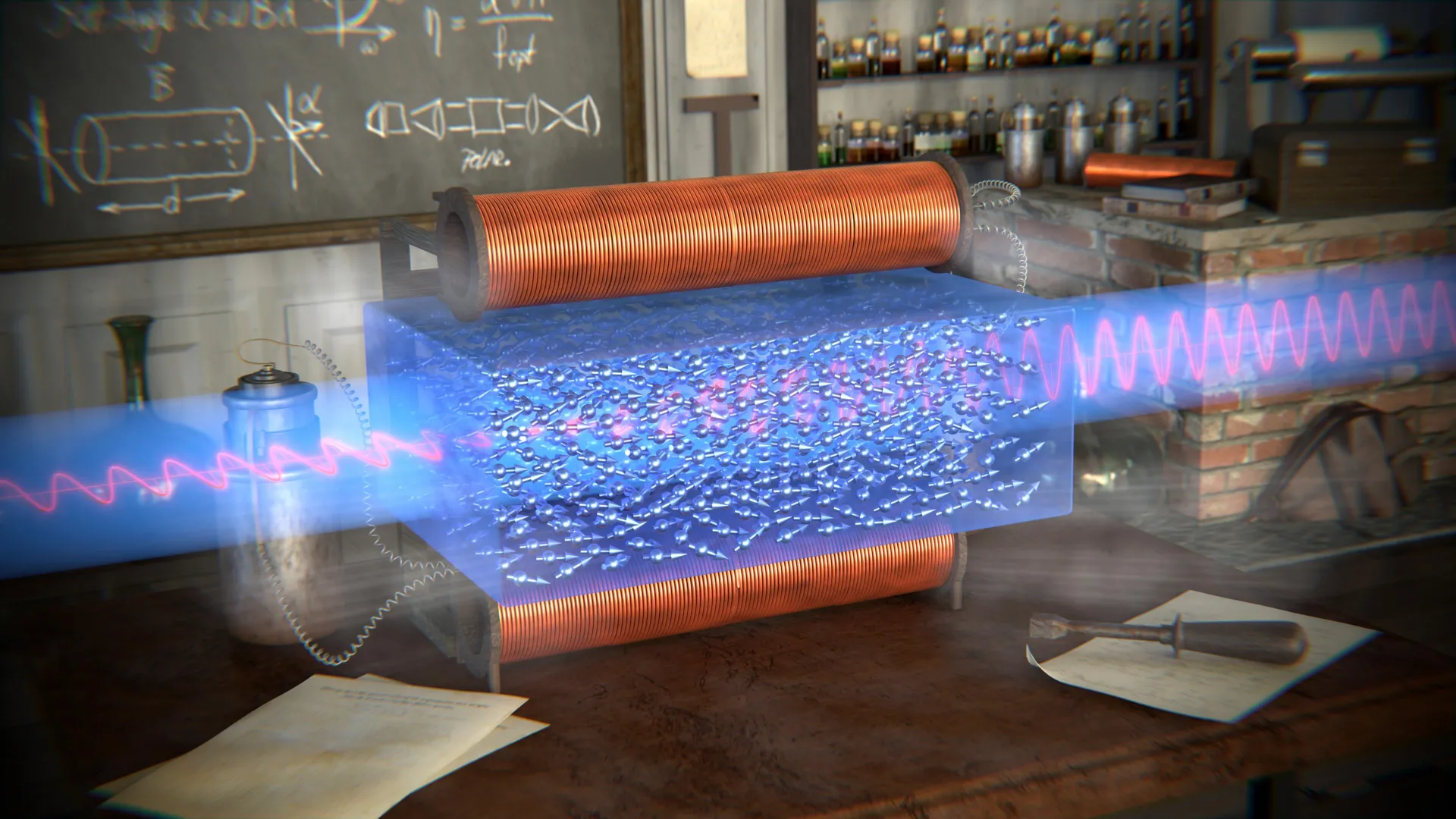

For nearly two centuries, the scientific community has operated under a fundamental understanding of how light interacts with matter, specifically regarding the phenomenon known as the Faraday Effect. This cornerstone of optics and magnetism dictates that when polarized light passes through a material subjected to an external magnetic field, its polarization plane rotates. For 180 years, the prevailing scientific consensus attributed this rotation solely to the interaction between the electric component of light and the electric charges within the material. However, groundbreaking research from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem has shattered this long-held assumption, revealing that the magnetic component of light plays a direct and significant role in the Faraday Effect. This paradigm-shifting discovery not only revises our fundamental understanding of light-matter interactions but also unlocks exciting new avenues for advancements in fields ranging from optics and spintronics to cutting-edge quantum technologies.

The seminal findings, meticulously detailed in a recent publication in Scientific Reports, a prestigious journal of Nature, demonstrate unequivocally that the magnetic portion of light exerts a measurable and meaningful influence on how light behaves when interacting with materials. This revelation directly contradicts a scientific explanation that has shaped the discourse and research in this domain since the 19th century, fundamentally altering our perception of light’s capabilities.

The extensive study, spearheaded by Dr. Amir Capua and Benjamin Assouline from the university’s distinguished Institute of Electrical Engineering and Applied Physics, provides the first robust theoretical evidence that the oscillating magnetic field inherent to light actively contributes to the Faraday Effect. This effect, named after the pioneering scientist Michael Faraday who discovered it in 1845, is a crucial phenomenon for understanding magneto-optical phenomena. It describes the rotation of the plane of polarization of light as it propagates through a medium that is under the influence of a static, external magnetic field. Until now, the accepted wisdom was that this interaction was a purely electric one, with light’s electric field dictating the dance with matter’s electric charges.

Dr. Capua articulates the core of their discovery with striking simplicity: "In simple terms, it’s an interaction between light and magnetism. The static magnetic field ‘twists’ the light, and the light, in turn, reveals the magnetic properties of the material. What we’ve found is that the magnetic part of light has a first-order effect, it’s surprisingly active in this process." This statement encapsulates the revolutionary nature of their findings. It posits that light is not merely a passive illuminator of the world but an active participant in magnetic phenomena, capable of exerting its own magnetic influence.

For almost two centuries, the scientific narrative surrounding the Faraday Effect was exclusively focused on the electric field of light. This electric field was understood to interact with the electric charges within the atoms and molecules of a material, causing them to precess or oscillate in a way that leads to the observed rotation of the light’s polarization. The magnetic field of light, a fundamental aspect of electromagnetic radiation, was largely considered a secondary player, its contribution to the Faraday Effect deemed negligible or insignificant. The new study, however, presents compelling evidence that this magnetic field of light plays a direct and crucial role by interacting with the intrinsic magnetic moments of electrons within atoms, known as atomic spins. This interaction with spins, long assumed to be a minor or even irrelevant factor in the Faraday Effect, has now been identified as a significant contributor.

The researchers employed sophisticated theoretical calculations, deeply informed by the principles of the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation. This fundamental equation is a cornerstone in the study of magnetism, describing the dynamics of magnetization in magnetic materials, particularly how magnetic moments respond to external magnetic fields and damping. By applying these advanced computational tools, the team was able to rigorously demonstrate that the magnetic field component of light possesses the capability to generate magnetic torque within a material. This torque acts in a manner analogous to how a static external magnetic field influences magnetic moments. Dr. Capua eloquently summarizes this crucial aspect: "In other words, light doesn’t just illuminate matter, it magnetically influences it." This assertion underscores the profound shift in understanding – light is not just a carrier of visual information but also a force capable of directly manipulating magnetic properties.

To quantify the extent of this newly identified magnetic influence, the research team meticulously applied their theoretical model to a well-characterized material: Terbium Gallium Garnet (TGG). TGG is a crystal commonly utilized in experimental studies of the Faraday Effect due to its favorable magneto-optical properties. Their detailed analysis, performed across different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, yielded astonishing results. They revealed that the magnetic component of light is responsible for a substantial portion of the observed polarization rotation. Specifically, in the visible spectrum, the magnetic field of light accounts for approximately 17% of the total rotation. This percentage escalates significantly in the infrared spectrum, where the magnetic influence of light can contribute as much as 70% to the observed Faraday rotation. These figures are not merely academic curiosities; they represent a fundamental revision of how we understand light’s interaction with matter.

Benjamin Assouline highlights the broader implications of their findings: "Our results show that light ‘talks’ to matter not only through its electric field, but also through its magnetic field, a component that has been largely overlooked until now." This analogy of "talking" emphasizes the active and communicative nature of light’s interaction with the material world. The electric field has been the primary language of this communication, but the magnetic field, it turns out, has been speaking a significant dialect all along, a dialect that has remained largely unheard and unappreciated.

The implications of this revised understanding of light’s magnetic behavior are far-reaching and have the potential to catalyze significant innovations across a spectrum of technological domains. The researchers foresee a future where this knowledge can be harnessed to develop more advanced optical data storage solutions. By understanding and manipulating the magnetic interaction of light, it might be possible to encode information with greater density and efficiency.

Furthermore, the field of spintronics, which focuses on exploiting the spin of electrons in addition to their charge for electronic devices, stands to benefit immensely. The ability of light to directly influence electron spins opens up new possibilities for creating novel spintronic devices with enhanced performance and functionality. This could lead to faster, more energy-efficient computing and memory technologies.

Perhaps most excitingly, this discovery holds significant promise for the advancement of emerging quantum technologies. Spin-based quantum computing, a particularly promising avenue for developing powerful quantum computers, relies heavily on the precise control and manipulation of quantum spins. The newfound understanding of how light’s magnetic field interacts with these spins could provide crucial new tools and techniques for controlling and entangling qubits, the fundamental units of quantum information. This could accelerate the development of robust and scalable quantum computers capable of solving problems currently intractable for even the most powerful classical supercomputers.

In conclusion, the research conducted at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem represents a monumental leap forward in our understanding of fundamental physics. By uncovering the long-hidden magnetic secret of light and its direct role in the Faraday Effect, these scientists have not only corrected a 180-year-old misconception but have also illuminated a path towards unprecedented technological advancements. The realization that light possesses a significant magnetic influence on matter opens a new chapter in optics, spintronics, and quantum information science, promising a future where the interplay between light and magnetism is harnessed in ways we are only just beginning to imagine.