For most, the irrational number π (pi), perpetually approximated as 3.14 and extending infinitely without any repeating pattern, is a familiar, albeit somewhat abstract, concept encountered during early explorations of geometry and circles in school. However, in recent decades, the relentless march of computational power has propelled π far beyond the confines of the classroom. Today, supercomputers capable of unimaginable processing speeds are employed to calculate π to an astonishing trillions of decimal places, a testament to humanity’s ongoing quest to understand this fundamental constant. Yet, as this new research powerfully demonstrates, the true significance of π, and particularly the formulas developed to capture its essence, transcends mere numerical precision.

The crux of this profound discovery lies in the work of Srinivasa Ramanujan, a mathematical prodigy whose prolific output continues to astound and inspire. In 1914, a pivotal year shortly before his departure from Madras for the intellectual hothouse of Cambridge, Ramanujan published a seminal paper that presented 17 distinct formulas for the calculation of π. These expressions were not just novel; they were revolutionary in their efficiency, enabling the computation of π with a speed and accuracy that far surpassed any existing techniques of the era. The sheer conciseness of these formulas, containing a remarkably small number of mathematical terms, belied their power, yielding an impressive deluge of accurate digits.

The enduring legacy of Ramanujan’s work is undeniable. His innovative methods have become cornerstones of modern mathematical and computational approaches to calculating π, forming the very bedrock upon which today’s most sophisticated algorithms are built. Aninda Sinha, a Professor at CHEP and the senior author of the recent study, elaborates on this point: "Scientists have computed pi up to 200 trillion digits using an algorithm called the Chudnovsky algorithm. These algorithms are actually based on Ramanujan’s work." This statement underscores the direct lineage from Ramanujan’s early 20th-century genius to the pinnacle of 21st-century computational mathematics.

However, for Professor Sinha and Faizan Bhat, the study’s lead author and a former IISc PhD student, the significance of Ramanujan’s formulas extended beyond their computational prowess. They were driven by a deeper, more fundamental question: why should such extraordinarily powerful and efficient formulas for π exist in the first place? Instead of accepting them as purely abstract mathematical curiosities, the research team embarked on a quest to find a physical explanation, a grounding in the tangible world that might illuminate their origins. "We wanted to see whether the starting point of his formulae fit naturally into some physics," Sinha explains. "In other words, is there a physical world where Ramanujan’s mathematics appears on its own?"

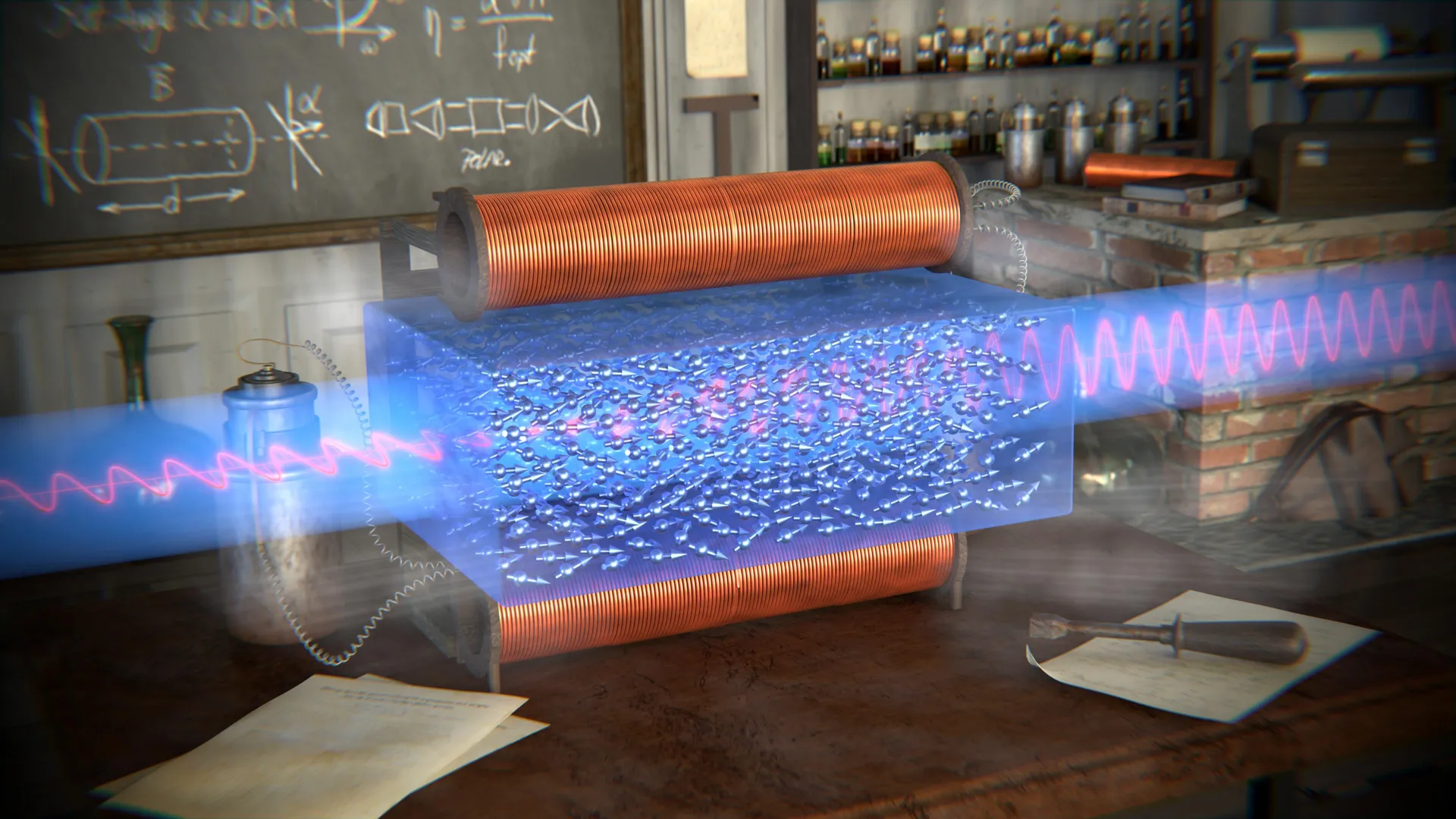

Their meticulous investigation led them down a fascinating theoretical path, converging on a broad and powerful family of physical theories known as conformal field theories (CFTs). More specifically, their focus sharpened on a particular subset: logarithmic conformal field theories (LCFTs). These theories are renowned for their ability to describe systems that exhibit a remarkable property known as scale invariance symmetry. This means that the system appears statistically the same, regardless of the scale at which it is observed, much like the self-similar patterns found in fractals.

The researchers identified familiar physical phenomena that exemplify this scale invariance. A prime example is the critical point of water, a precise temperature and pressure at which the distinct phases of liquid water and water vapor become indistinguishable. At this critical juncture, water molecules exhibit scale invariance, and their complex behavior can be elegantly described using the framework of conformal field theory. This same principle of critical behavior, governed by LCFTs, extends to other complex natural processes, including percolation – the way substances spread through porous materials – and the nascent stages of turbulence in fluids. Intriguingly, certain theoretical models of black holes also fall within the purview of LCFTs, suggesting a surprising universality of these physical descriptions.

The breakthrough moment arrived when the IISc researchers discovered that the underlying mathematical structure that gives Ramanujan’s pi formulas their power and elegance is precisely the same mathematical framework that underpins these logarithmic conformal field theories. This shared structural DNA meant that by leveraging the insights from Ramanujan’s work, they could devise more efficient ways to compute crucial quantities within these complex physical theories. This innovative approach holds the promise of significantly enhancing scientists’ ability to model and understand intricate natural processes like the unpredictable nature of turbulence and the diffusive spread in percolation systems.

The researchers draw a compelling parallel between their findings and Ramanujan’s own celebrated method. Just as Ramanujan could begin with a compact mathematical expression and rapidly arrive at highly accurate values for π, the IISc team found they could use the inherent structure of his formulas to streamline complex physics calculations. "In any piece of beautiful mathematics, you almost always find that there is a physical system which actually mirrors the mathematics," notes Bhat. "Ramanujan’s motivation might have been very mathematical, but without his knowledge, he was also studying black holes, turbulence, percolation, all sorts of things." This suggests that Ramanujan, in his profound mathematical explorations, was inadvertently touching upon the fundamental physics that governs these phenomena.

In essence, the findings serve as a powerful testament to the enduring relevance of insights born over a century ago. Ramanujan’s formulas, conceived in the early 20th century, now offer a previously unrecognized advantage, making high-energy physics calculations more manageable and potentially accelerating scientific discovery. Beyond their immediate practical utility, this work underscores the extraordinary, almost prophetic, reach of Ramanujan’s mathematical genius. "We were simply fascinated by the way a genius working in early 20th century India, with almost no contact with modern physics, anticipated structures that are now central to our understanding of the universe," Sinha concludes, his voice imbued with a sense of awe. The universe, it seems, continues to whisper its secrets through the elegant language of numbers, and Ramanujan’s century-old formulas are proving to be an indispensable key to deciphering them.