The reason for her ban became clear when U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio posted on X, promoting a conspiracy theory he termed the "censorship-industrial complex." This theory alleges a widespread conspiracy between the U.S. government, tech companies, and civil society organizations to suppress conservative viewpoints – the very narrative that HateAid has recently become entangled in. Subsequently, Undersecretary of State Sarah B. Rogers posted on X the names of those targeted by travel bans. The list included Ballon and her co-director, Anna Lena von Hodenberg, along with three others involved in similar work: former EU commissioner Thierry Breton, a key architect of Europe’s Digital Services Act (DSA); Imran Ahmed of the Center for Countering Digital Hate, which monitors social media hate speech; and Clare Melford of the Global Disinformation Index, which assesses the risk of advertising on sites promoting hate speech and disinformation.

This action represents an escalation in the Trump administration’s campaign against digital rights, waged under the banner of free speech. However, EU officials, free speech experts, and the five individuals affected vehemently deny the censorship accusations. Ballon and von Hodenberg, along with some of their clients, emphasize that their work is fundamentally about enhancing online safety. Their recent experiences highlight the increasingly politicized and precarious nature of their online safety advocacy, and they are unlikely to be the last to face such measures.

Ballon was the one to inform von Hodenberg about their inclusion on the list. "We kind of felt a chill in our bones," von Hodenberg shared in early January. However, she quickly added, "Okay, it’s the old playbook to silence us." They immediately began working to counter the narrative pushed by the U.S. government. Within hours, Ballon and von Hodenberg issued a strong statement refuting the allegations: "We will not be intimidated by a government that uses accusations of censorship to silence those who stand up for human rights and freedom of expression," they declared. "We demand a clear signal from the German government and the European Commission that this is unacceptable. Otherwise, no civil society organisation, no politician, no researcher, and certainly no individual will dare to denounce abuses by US tech companies in the future."

These signals of support were swift. German Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul stated on X that the entry bans were "not acceptable," emphasizing that the DSA was "democratically adopted by the EU, for the EU—it does not have extraterritorial effect." French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted that the measures "amount to intimidation and coercion aimed at undermining European digital sovereignty." The European Commission issued a statement strongly condemning the Trump administration’s actions and reaffirming its "sovereign right to regulate economic activity in line with our democratic values."

Ahmed, Melford, Breton, and their respective organizations also released statements denouncing the bans. Ahmed, the only individual based in the U.S., successfully filed a lawsuit to prevent potential detention, which the State Department had indicated it might consider. Beyond official condemnations, Ballon and von Hodenberg received practical advice: anticipate further consequences, as the travel ban might just be the beginning. This included warnings that service providers could revoke account access, banks might restrict financial transactions, and malicious actors might attempt to seize personal data. Allies even suggested moving money to friends’ accounts or keeping cash on hand for essential expenses.

These concerns were amplified by the Trump administration’s recent sanctions against two International Criminal Court judges for "illegitimate targeting of Israel." These sanctions resulted in the judges losing access to American tech platforms like Microsoft, Amazon, and Gmail. "If Microsoft does that to someone who is a lot more important than we are," Ballon noted, "they will not even blink to shut down the email accounts from some random human rights organization in Germany." Von Hodenberg added, "We have now this dark cloud over us that any minute, something can happen. We’re running against time to take the appropriate measures."

Navigating a "Lawless Place"

Founded in 2018 to assist individuals facing digital violence, HateAid has expanded its mission to defend broader digital rights. The organization provides channels for reporting illegal online content, offers victims advice, digital security support, emotional counseling, and assistance with evidence preservation. It also educates German law enforcement, prosecutors, and politicians on handling online hate crimes. When HateAid is contacted and its lawyers determine that harassment likely violates the law, the organization connects victims with legal counsel for civil and criminal lawsuits against perpetrators, sometimes providing financial assistance for these cases. Ballon and von Hodenberg estimate that HateAid has supported approximately 7,500 victims, facilitating 700 criminal and 300 civil cases, primarily against individual offenders.

For Theresia Crone, a 23-year-old German law student and activist, HateAid’s support has been instrumental in regaining control of her life, both online and offline. After discovering online forums dedicated to creating deepfakes of her, she sought HateAid’s help. Without them, she explained, she would have had to rely solely on the police and public prosecutor to handle the case or bear the significant financial burden of hiring an attorney as a student with no fixed income. The process of documenting everything alone would have been deeply retraumatizing, forcing her to repeatedly confront the disturbing content.

"The internet is a lawless place," Ballon stated in mid-December, a few weeks before her travel ban. In HateAid’s Berlin office, she explained that many cases go unprosecuted due to unidentified perpetrators. This reality drives the nonprofit’s advocacy for stronger laws and regulations governing technology companies in Germany and across the EU. HateAid has also engaged in strategic litigation against platforms, such as their 2023 lawsuit against X for failing to enforce its terms of service against antisemitic content and Holocaust denial, which is illegal in Germany. This action likely drew the attention of X owner Elon Musk and made HateAid a target of Germany’s far-right party, the Alliance for Democracy, which Musk has praised.

HateAid Caught in Trump World’s Dragnet

HateAid’s profile in online safety work grew significantly when it was designated as a trusted flagger organization under the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) in June 2024. The DSA, enacted in 2022, mandates social media companies to remove illegal content, including hate speech and incitement to violence, and to enhance transparency by allowing more appeals on moderation decisions. Trusted flaggers, designated by EU countries, play a crucial role in DSA enforcement by identifying illegal content. While anyone can report such content, trusted flaggers’ reports are prioritized and legally require a response from platforms.

The Trump administration has vociferously argued that the trusted flagger program and the DSA are forms of censorship that disproportionately target right-wing voices and American technology companies like X. Ballon refuted these claims, stating, "We don’t delete content, and we also don’t, like, flag content publicly for everyone to see and to shame people. The only thing that we do: We use the same notification channels that everyone can use, and the only thing that is in the Digital Services Act is that platforms should prioritize our reporting." The responsibility for action then rests with the platforms.

Despite this, the narrative of HateAid and similar organizations censoring the right has evolved into a potent conspiracy theory with tangible repercussions. In 2025, MIT Technology Review reported on the closure of a small State Department office following "censorship" allegations, as well as an unusual attempt by State leadership to access internal records related to supposed censorship, including information about Medford, Ahmed, and their organizations.

HateAid experienced a surge in harassment starting in February 2025, following a 60 Minutes documentary on German hate speech laws that featured Ballon’s quote, "free speech needs boundaries, which are part of our constitution." This aired shortly before Vice President JD Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, where he warned of "free speech…in retreat" across Europe, intensifying hostility towards Ballon and her organization. In July 2025, a report by Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives claimed the DSA "compels censorship and infringes on American free speech," explicitly naming HateAid. Ballon described her work as having become "more dangerous," noting that attacks, previously directed at their clients who were activists and journalists, had become "more personal."

Consequently, over the past year, HateAid has implemented measures to safeguard its reputation and proactively address damaging narratives. Ballon has filed more hate speech complaints against herself than in her entire career and has initiated defamation lawsuits on behalf of HateAid. These tensions culminated in December 2025 when the European Commission fined X $140 million for DSA violations. This prompted further accusations of right-wing censorship, with Trump calling the fine "a nasty one" and warning, "Europe has to be very careful." Just weeks later, the travel bans were enacted.

Who Defines—and Experiences—Free Speech

Digital rights groups are challenging the Trump administration’s narrow interpretation of free speech and censorship. David Greene, civil liberties director at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, observes that this administration views free expression not as a fundamental human right for all, but as an expectation that "if anybody else’s speech is challenged, there’s a good reason for it, but it should never happen to them." Since Trump’s second term, social media platforms have scaled back their commitments to trust and safety. Meta, for instance, ended fact-checking on Facebook and adopted much of the administration’s censorship rhetoric, with CEO Mark Zuckerberg stating his intention to "work with President Trump to push back on governments around the world" that are perceived as "going after American companies and pushing to censor more."

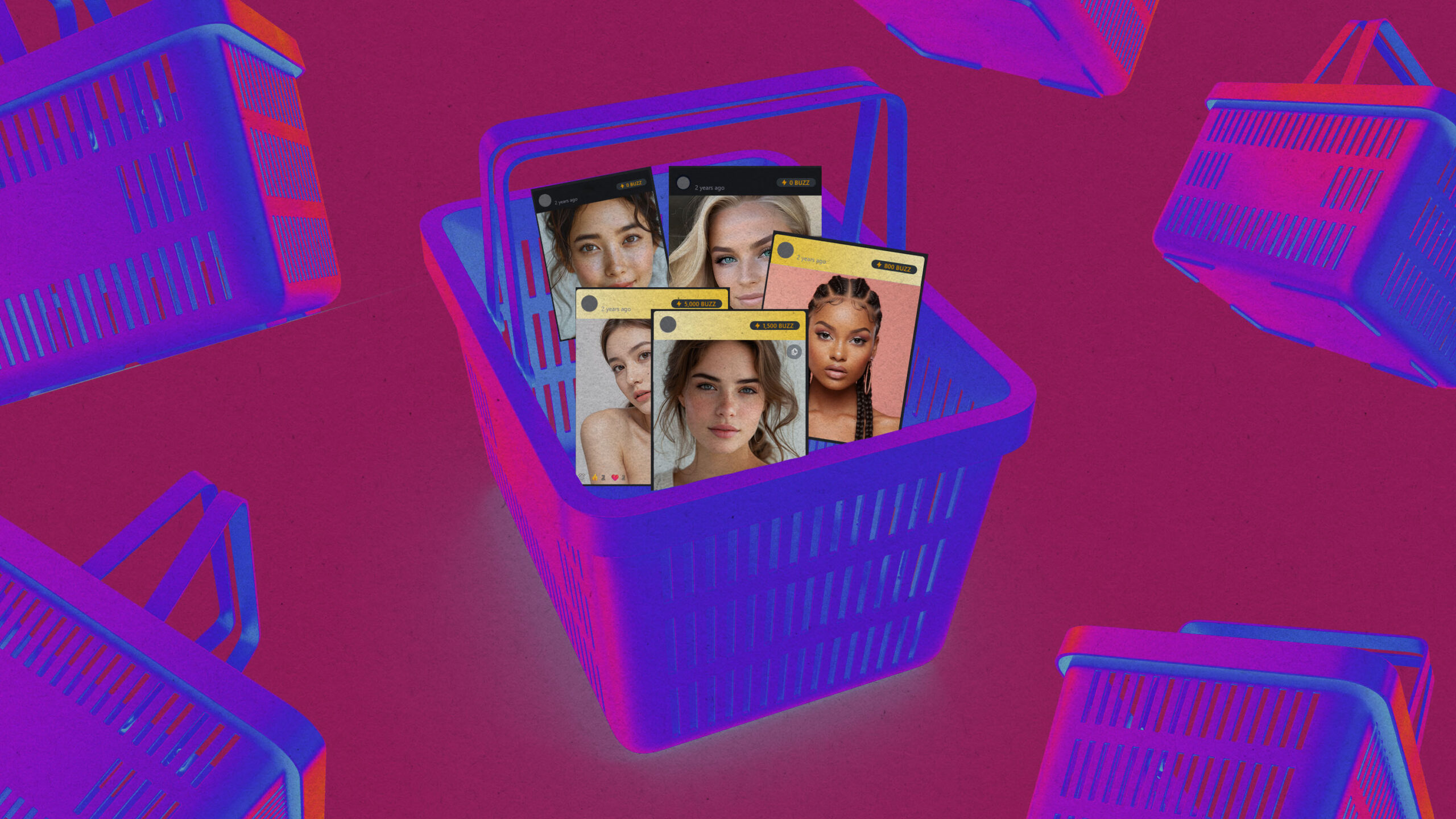

X has gone further in disregarding European law and user rights protected by the DSA. In a notable instance, X allowed users to generate nonconsensual nude images of women and children using its AI tool, Grok, with minimal restrictions and few immediate consequences. (X later announced limitations on explicit image generation with Grok.) Ballon believes this is a strategic business decision: "You can better make money if you don’t have to implement safety measures and don’t have to invest money in making your platform the safest place."

Von Hodenberg added, "It goes both ways. It’s not only the platforms who profit from the US administration undermining European laws—but also, obviously, the US administration also has a huge interest in not regulating the platforms—because who is amplified right now? It’s the extreme right." She posits that this explains why HateAid, along with Ahmed’s and Melford’s organizations, and Breton, have been targeted: their work disrupts an "unholy deal where the platforms profit economically and the US administration is profiting in dividing the European Union."

These travel restrictions send a clear message to all organizations working to hold tech companies accountable. Greene calls them "purely vindictive," designed to "punish people from pursuing further work on disinformation or anti-hate work." The State Department did not respond to requests for comment. Ultimately, these actions impact who feels safe participating online.

Ballon referenced research on the "silencing effect" of harassment and hate speech, which impacts not only those directly attacked but also witnesses. This effect is particularly pronounced for women, who disproportionately face more sexualized and violent online hate. The situation will worsen if organizations like HateAid face deplatforming or funding cuts. Von Hodenberg succinctly stated, "They reclaim freedom of speech for themselves when they want to say whatever they want, but they silence and censor the ones that criticize them."

Despite these challenges, the HateAid directors remain resolute. They are taking all received advice seriously, particularly regarding "becoming more independent from service providers," Ballon stated. "Part of the reason that they don’t like us is because we are strengthening our clients and empowering them," said von Hodenberg. "We are making sure that they are not succeeding, and not withdrawing from the public debate. So when they think they can silence us by attacking us? That is just a very wrong perception." Martin Sona contributed reporting.