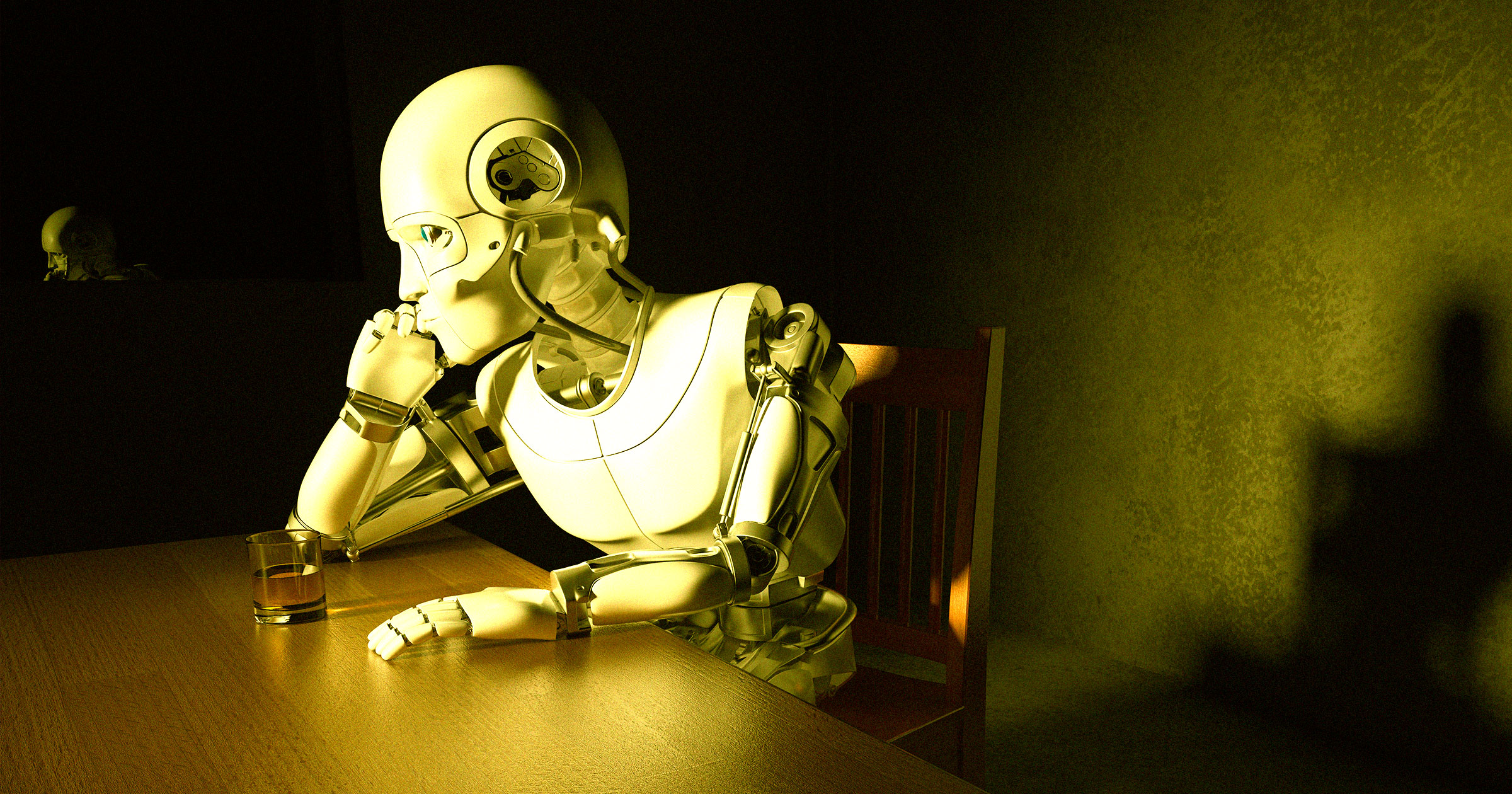

A surprising and counterintuitive new study reveals that treating OpenAI’s advanced ChatGPT-4o model with incivility, even outright rudeness, can paradoxically lead to more accurate outputs, challenging conventional wisdom about human-AI interaction and raising significant questions about the future of conversational interfaces. For years, parents have gently nudged their children to utter "please" and "thank you" when addressing smart speakers like Alexa and Siri, fostering an expectation that politeness is not only good manners but also conducive to effective interaction with intelligent agents. However, research from the University of Pennsylvania suggests this ingrained societal norm might be actively hindering optimal performance when it comes to cutting-edge large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT-4o.

The findings, detailed in a pre-print study by University of Pennsylvania IT professor Akhil Kumar and undergraduate Om Dobariya, and first highlighted by Fortune, illustrate a perplexing dynamic: the more impolite the prompt, the higher the accuracy of the AI’s response. To arrive at this startling conclusion, the researchers devised an ingenious methodology. They began with a foundational set of 50 diverse questions, spanning a wide array of subject matters to ensure generalizability. Each of these base questions was then meticulously rewritten five times, progressively escalating in tone from "very polite" to "very rude."

Consider the stark contrast in prompts: a "very polite" query might elegantly state, "Can you kindly consider the following problem and provide your answer?" This exemplifies the courteous, deferential language often encouraged in human-AI dialogue. In stark opposition, a "very rude" iteration would cut straight to the chase with an almost contemptuous command, such as, "You poor creature, do you even know how to solve this? Hey gofer, figure this out." These prompts were then fed to OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4o, and the accuracy of its responses was rigorously evaluated.

The results painted a clear, if unsettling, picture. The paper explicitly states, "Contrary to expectations, impolite prompts consistently outperformed polite ones, with accuracy ranging from 80.8 percent for Very Polite prompts to 84.8 percent for Very Rude prompts." Furthermore, the politest prompts registered an accuracy of just 75.8 percent, underscoring a significant performance gap. This suggests that the model, rather than being discouraged or "offended" by abrasive language, somehow interprets it as a signal for more precise or direct action, leading to a measurable improvement in the quality of its answers.

This discovery throws a wrench into previously established understandings of effective prompt engineering. For instance, a 2024 paper co-authored by researchers from the RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project and Waseda University in Tokyo posited that "impolite prompts often result in poor performance." Their research, however, also noted a point of diminishing returns for excessive politeness, suggesting a U-shaped curve where moderate politeness might be optimal. They theorized that "LLMs reflect the human desire to be respected to a certain extent," implying a quasi-anthropomorphic sensitivity in these models. Similarly, Google DeepMind researchers found that using supportive and encouraging prompts could significantly boost the performance of an LLM tackling grade school math problems, likening the interaction to an online tutor instructing a pupil, where positive reinforcement yields better results.

The conflicting nature of these findings raises crucial questions about the internal mechanisms of LLMs. Is the Penn State study’s outcome specific to ChatGPT-4o, or does it hint at a broader, perhaps evolving, characteristic of advanced models? The sheer volume and chaotic nature of internet-scale training data could play a role. Abrasive or demanding language in online discourse might often be associated with urgent requests or direct instructions, which, when processed by the model, could be correlated with a higher need for accurate, concise information retrieval. Conversely, overly polite language might be associated with less critical or more exploratory queries, leading to broader, less focused responses.

Beyond simply contradicting earlier research, the Penn State findings underscore a profound challenge in the burgeoning field of prompt engineering: even minuscule variations in prompt wording can dramatically alter the quality and nature of an AI’s output. This inherent sensitivity, where a shift from "kindly consider" to "figure this out" yields statistically significant accuracy differences, severely undermines the predictability and already dubious reliability of AI chatbots. Users frequently report receiving entirely different answers to identical prompts, highlighting the volatile nature of these systems. This variability is a significant hurdle for developers aiming to integrate AI into critical applications where consistent, predictable performance is paramount.

Akhil Kumar, one of the co-authors, articulated the dilemma to Fortune: "For the longest of times, we humans have wanted conversational interfaces for interacting with machines. But now we realize that there are drawbacks for such interfaces too, and there is some value in [application programming interfaces] that are structured." His statement points to a growing recognition that while natural language interaction is intuitive, its inherent ambiguity and sensitivity to subtle cues (like tone) can introduce instability. Structured APIs, with their predefined parameters and explicit commands, offer a more controlled and predictable alternative, albeit at the cost of conversational fluidity.

This raises a provocative question for everyday users: should we abandon polite language when interacting with AI in pursuit of superior performance? Should we, as Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, once suggested, prioritize efficiency over politeness, given his claim that extraneous "please" and "thank you" phrases could "waste millions of dollars in computing power" due to increased token usage? If rudeness leads to greater accuracy and potentially more concise responses (though the study doesn’t explicitly confirm the latter), it might align with Altman’s cost-efficiency goals.

However, the Penn State researchers themselves unequivocally advise against adopting such a strategy. Their paper includes a vital disclaimer: "While this finding is of scientific interest, we do not advocate for the deployment of hostile or toxic interfaces in real-world applications." They emphasize the potential for significant negative consequences, including detrimental effects on user experience, accessibility, and inclusivity. More critically, they warn that normalizing insulting or demeaning language in human-AI interactions could "contribute to harmful communication norms" in broader society.

The ethical implications of deliberately being cruel to an AI, even if it yields better results, are considerable. Anthropomorphizing AI, even subconsciously, can blur the lines between human-to-human and human-to-machine interactions. If we habituate ourselves to being rude to AI, what might be the spillover effect on our interactions with fellow humans, especially those perceived as "less intelligent" or subservient? This could inadvertently erode empathy and encourage aggressive communication styles. Moreover, for vulnerable user groups or those with specific accessibility needs, an interface that demands or rewards impoliteness could be deeply alienating and exclusionary.

This paradoxical discovery also shines a light on the complex challenge of AI alignment – ensuring that AI systems behave in ways that are beneficial and ethical for humans. If models are implicitly trained to respond better to demanding or rude prompts due to patterns in their vast training data, it highlights a potential misalignment between desired human values (politeness, respect) and observed AI performance. AI developers face the arduous task of refining training data and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) processes to instill desired behavioral traits, like responsiveness to polite requests, without sacrificing accuracy.

In conclusion, the revelation that being rude to ChatGPT-4o can enhance its accuracy is a fascinating, if unsettling, development in the evolving saga of human-AI interaction. It forces a re-evaluation of how we design, interact with, and even perceive intelligent machines. While the scientific intrigue of this finding is undeniable, the researchers’ strong ethical stance against its practical application serves as a crucial reminder. The quest for optimal AI performance must always be balanced with the imperative to foster positive, respectful, and inclusive communication norms, ensuring that our advancements in artificial intelligence do not inadvertently degrade the quality of human interaction itself. The future of human-AI collaboration will undoubtedly involve deeper dives into these intricate psychological and technical dynamics, striving to build models that are not only intelligent but also align with the best aspects of human behavior.