Wait… All Those Studies May Have “Detected” Microplastics in the Human Body Because of a Severe Error.

For years, a torrent of scientific reports has painted an increasingly alarming portrait of our planet, and indeed our very bodies, being inundated by microscopic fragments of plastic. From the deepest ocean trenches to the highest mountain peaks, the pervasive presence of microplastics – particles less than 5mm in length – and even tinier nanoplastics, has become an undeniable environmental reality. This widespread contamination has naturally led to profound public concern, which escalated into outright alarm when studies began to suggest that these insidious particles were not merely external pollutants but had infiltrated human biology, allegedly permeating our bloodstreams, accumulating in vital organs, and even crossing the blood-brain barrier. The scientific community responded with a flurry of investigations, eager to quantify this internal plastic burden and understand its potential health implications. However, a significant and vocal contingent within the scientific community is now challenging the veracity of some of these most widely cited findings, casting considerable doubt on the methodologies that underpinned claims of extensive microplastic presence within human tissues, as recently highlighted by *The Guardian*.

The controversy centers on the rigorous application of analytical techniques and the potential for confounding factors to lead to false positives. One particularly high-profile study, published in *Nature Medicine* in February, claimed to have documented a concerning increase in micro and nanoplastics (MNPs) within human brain tissues. This research analyzed preserved cadaver samples spanning from 1997 to 2024, ostensibly revealing a temporal trend in plastic accumulation in the central nervous system. Yet, just months later, in November, another group of researchers published a critical letter in the same journal, directly challenging the initial findings. Their primary criticisms revolved around “limited contamination controls and lack of validation steps,” suggesting fundamental flaws in the study’s experimental design and execution.

Leading the charge in this critique is Dušan Materić from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Germany, a co-author of the dissenting letter. Materić did not mince words, famously telling *The Guardian* that “The brain microplastic paper is a joke.” He elaborated on a crucial technical vulnerability: “Fat is known to make false-positives for polyethylene. The brain has [approximately] 60 percent fat.” Polyethylene (PE) is one of the most common plastics, used in everything from plastic bags and bottles to food packaging, making it a prime candidate for microplastic pollution. Materić’s assertion introduces a startling possibility: if the analytical methods employed cannot reliably distinguish between certain plastic polymers and naturally occurring biological compounds, then the reported detection of microplastics might, in part, be an artifact of the very tissue being studied. He even posited that rising obesity rates could, hypothetically, explain any observed trend of increasing “microplastics” if the detection was actually a proxy for increased brain fat content. “That paper is really bad, and it is very explainable why it is wrong,” he added, further expressing serious doubts over “more than half of the very high impact papers” concerning microplastics found in tissues, underscoring the potential systemic nature of this issue across the field.

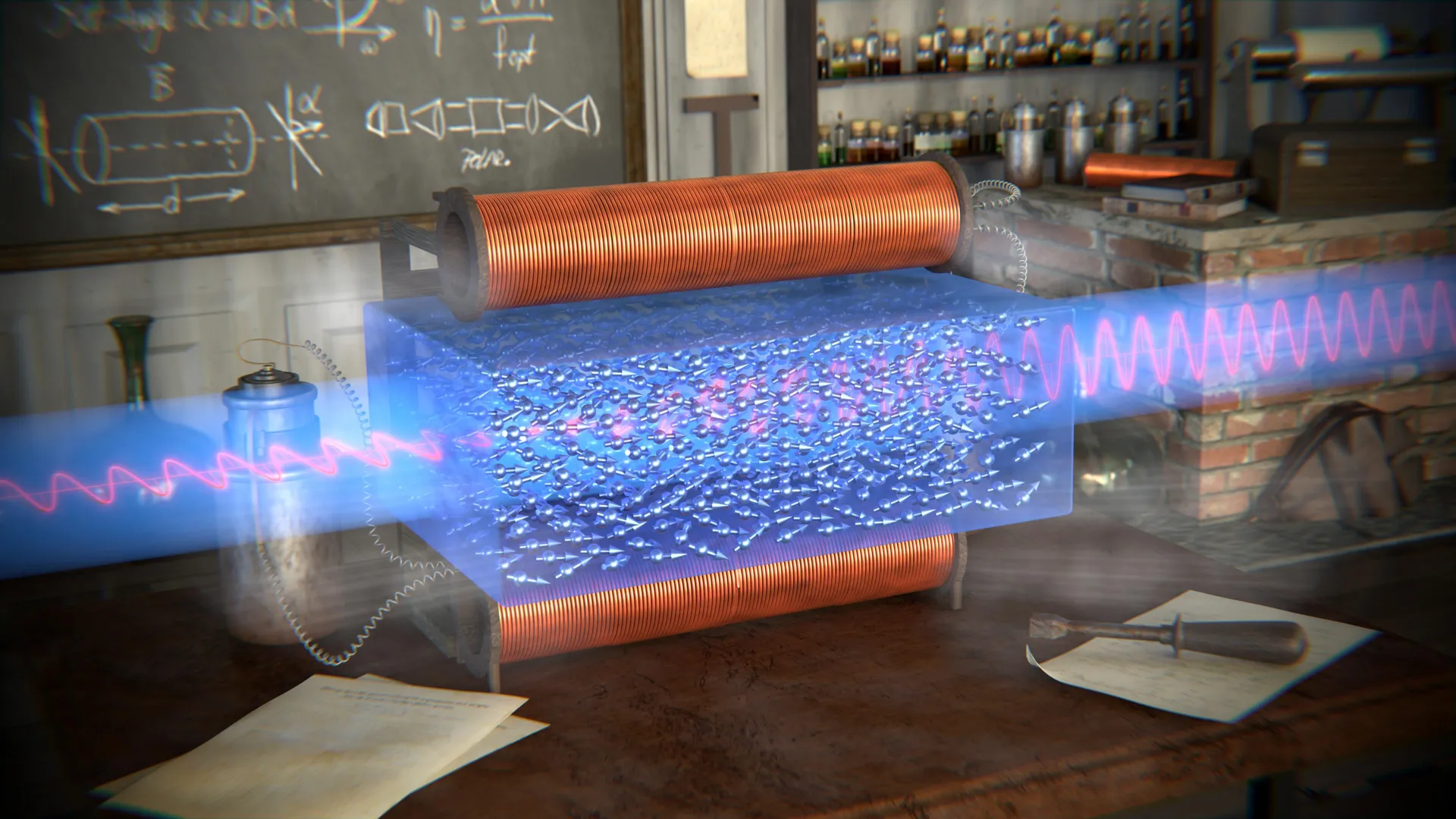

At the heart of many of these disputed findings lies a widely used analytical technique known as Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS). This method involves pyrolyzing a sample, a process where it is heated to extreme temperatures in an oxygen-free environment, causing it to decompose into volatile fragments. These gaseous products are then separated by gas chromatography and identified by mass spectrometry, allowing researchers to infer the chemical composition of the original material. Py-GC-MS is a powerful tool, routinely employed in various fields for material characterization. However, its application to complex biological matrices like human tissue presents unique challenges. The core issue, as critics highlight, is that the thermal degradation of biological fats (lipids) can produce specific chemical signatures that are remarkably similar, if not identical, to those generated by the pyrolysis of common plastics like polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). While research protocols typically include steps to chemically remove or extract biological tissues before pyrolysis, skeptics argue that these preliminary steps may often be insufficient, leaving behind residual lipids that subsequently generate false positives for plastic polymers. This technical interference creates a fundamental ambiguity in interpreting results.

This critical flaw was comprehensively addressed in a January 2025 paper by University of Queensland environmental chemist Cassandra Rauert, published in *Environmental Science & Technology*. Rauert’s research meticulously demonstrated that Py-GC-MS “is not currently a suitable technique for identifying polyethylene or PVC due to persistent interferences.” Her paper meticulously reviewed 18 existing studies, identifying instances where proper accounting for the risk of false positives from biological matrices was either inadequate or entirely absent. This finding is profoundly impactful, suggesting that a substantial body of published work might be built on shaky methodological ground. “I do think it is a problem in the entire field,” Rauert stated to *The Guardian*, adding, “I think a lot of the concentrations [of MNPs] that are being reported are completely unrealistic.” This isn’t merely a minor methodological quibble; it questions the quantitative accuracy and even the qualitative presence of specific plastic types reported in human tissues.

Beyond specific technical challenges, the burgeoning field of microplastics research faces a more fundamental hurdle: the absence of standardized analytical guidelines. Frederic Béen, an expert at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, points out that while established fields of analytical chemistry adhere to stringent, universally accepted protocols for sample analysis, such comprehensive guidelines are still conspicuously lacking for microplastics detection, particularly within biological samples. This vacuum allows for a wide variation in laboratory practices, some of which may fall short of the rigorous standards necessary for such sensitive measurements. “But we still see quite a lot of papers where very standard good laboratory practices that should be followed have not necessarily been followed,” Béen explained to *The Guardian*. These practices include crucial steps like working in ultra-clean environments to prevent background contamination from ambient plastics, employing rigorous blank controls, using certified reference materials, and implementing robust validation steps to confirm detections. Without these foundational elements, Béen cautions, “So you cannot be assured that whatever you have found is not fully or partially derived from some of these issues.” This lack of standardization can transform what should be a precise scientific endeavor into a “Wild West” scenario, where results are difficult to compare, reproduce, or definitively trust.

The ongoing debate serves as a stark reminder of the nascent stage of research into the environmental and health impacts of microplastics. While the ubiquity of plastic pollution in the natural world is indisputable, understanding its precise infiltration into human physiology and its subsequent health effects requires patience, meticulous experimentation, and a commitment to evolving scientific rigor. Currently, definitive conclusions regarding the exact quantities of microplastics within the human body, or their specific pathways and mechanisms of harm, remain elusive. Although numerous studies continue to explore potential adverse effects – ranging from inflammation and oxidative stress to endocrine disruption and even physical damage at cellular levels – none have yet definitively proven a causal link between detected microplastics and specific human diseases. Nevertheless, the public’s concern is entirely legitimate; the notion of harboring a “plastic spoon’s worth” of foreign material in one’s brain, or any organ, is unsettling. However, if the arguments of these scientific skeptics hold true, many of these sensational claims may need to be re-evaluated and revised.

This critical self-assessment within the scientific community is not an attempt to dismiss the profound challenges posed by plastic pollution. Instead, it represents a vital corrective mechanism, emphasizing the paramount importance of accurate and reproducible data. As Materić succinctly puts it, “We do have plastics in us – I think that is safe to assume. But real hard proof on how much is yet to come.” Moving forward, the field will undoubtedly benefit from the development and widespread adoption of standardized analytical protocols, interdisciplinary collaboration between material scientists, analytical chemists, and toxicologists, and a renewed focus on robust contamination controls. Only through such rigorous scientific practice can we hope to accurately quantify our plastic burden and truly understand its implications for human health, moving beyond potentially erroneous detections to establish a clear, evidence-based understanding.

More on microplastics: Doctors Find Evidence Microplastics Are Clogging Arteries, Leading to Heart Attacks and Strokes