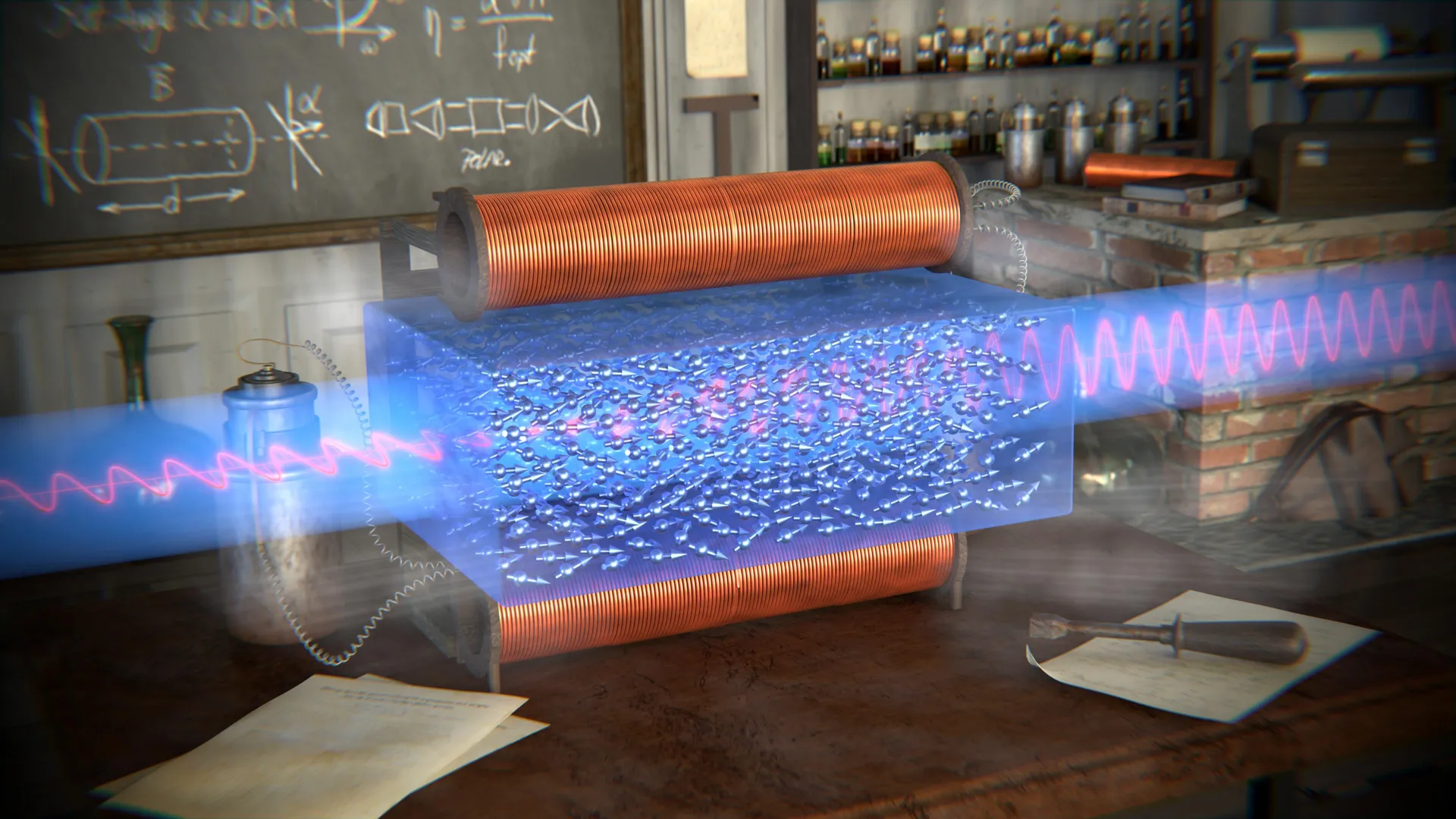

The profound and often surprising ways in which the human body adapts, or struggles to adapt, to the extreme environment of space continue to be a focal point for scientific inquiry. For decades, researchers have diligently studied how prolonged periods in microgravity can impact astronaut health, revealing a complex array of physiological changes. The absence of Earth’s constant gravitational pull has been definitively linked to an accelerated rate of bone density loss, weakening the skeletal structure and increasing fracture risk. Similarly, the destruction of red blood cells is a known consequence, leading to a condition sometimes referred to as “space anemia.” Furthermore, the unique fluid shifts in microgravity can exert pressure on the eyes, potentially leading to long-term vision problems, a condition known as Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS). These are just a few examples among many health conditions that arise, making this an especially critical area of research, particularly as agencies like NASA face real-time challenges, such as the recent need for evacuating an astronaut from the International Space Station due to an unspecified health crisis.

Beyond the more commonly discussed issues of bones, blood, and vision, a new and particularly tangible area of concern has emerged: the human brain. Suspended delicately within the skull in protective cerebrospinal fluid, the brain is not immune to the unique stresses of microgravity, and its response is proving to be surprisingly dynamic. A groundbreaking new study, published in the esteemed journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), by an international consortium of researchers, details these profound changes. The study, which represents a significant leap in our understanding, reveals that the brain literally “shifts upward and backward within the skull following spaceflight, with sensory and motor regions exhibiting the largest shifts.” This isn’t merely a subtle adjustment; the brain’s very shape also deforms in measurable ways, with some of these structural alterations persisting for over six months after an astronaut’s return to Earth.

Unpacking the Discovery: Brain Shifts and Deformations

This finding marks a truly notable advance in space medicine and neuroscience, adding another layer of complexity to the already extensive list of long-term health risks associated with extended periods in space. It underscores the incredible adaptability, yet also the inherent vulnerabilities, of the human body when removed from its evolutionary environment. Astronauts, upon returning to Earth, are not immediately ready to resume normal life. They conventionally undergo rigorous post-flight recovery programs designed to help them readjust to Earth’s gravity. Simple tasks like maintaining orientation, walking in a straight line, or even standing upright can become surprisingly difficult. This is largely because the brain, having adapted to a weightless environment where the vestibular system (inner ear) no longer functions as it does on Earth, is forced to relearn how to interpret sensory information and coordinate movement in a gravitational field. The newly identified brain displacement and deformation likely play a significant role in these post-flight challenges, adding a physical dimension to what was previously understood mainly as a neurological re-calibration.

The implications of these structural brain changes are vast and far-reaching, particularly as humanity sets its sights on deeper space exploration, including missions to the Moon and Mars that will necessitate even longer periods away from Earth. If the very architecture of the brain is being physically altered, understanding the full scope of these changes is paramount for ensuring astronaut safety and mission success. As the researchers themselves emphasized in their paper, “The health and human performance implications of these spaceflight-associated brain displacements and deformations require further study to pave the way for safer human space exploration.” This highlights an urgent need for continued research into the mechanisms behind these changes, their potential functional consequences, and strategies for mitigation.

Methodology: Peering Inside Astronaut Brains

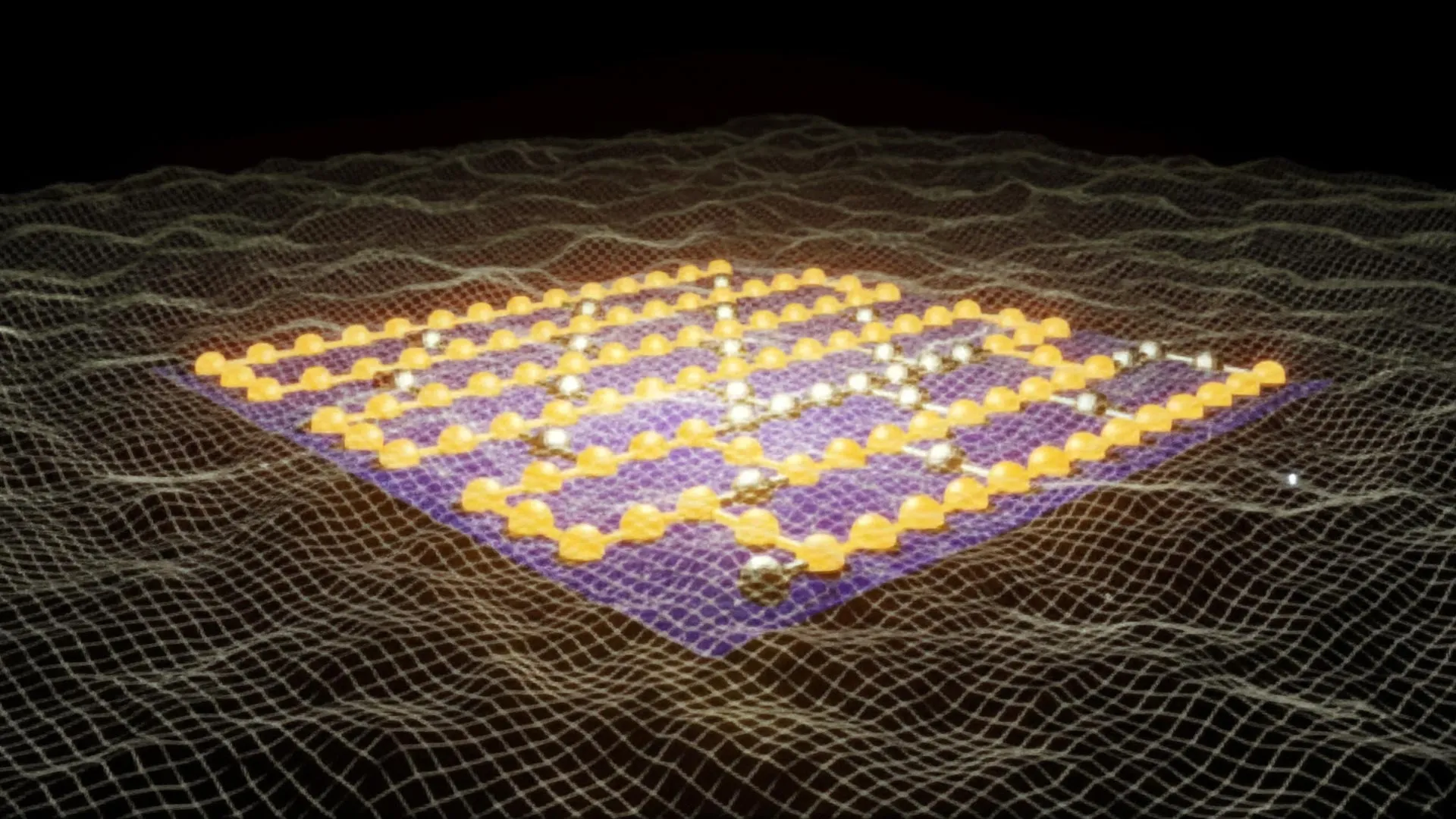

To arrive at these critical findings, the research team employed sophisticated techniques, analyzing pre- and post-flight MRI data from 26 astronauts who had undertaken various missions. To provide a crucial comparative baseline, they also analyzed MRI data from a control group involved in a “long-duration head-down tilt bed rest study.” This unique control study involved 24 non-astronaut participants who were instructed to lie at a six-degree incline with their heads positioned below their feet for periods up to 60 days. The head-down tilt position is a well-established ground-based analog for simulating some of the physiological fluid shifts experienced in microgravity, particularly the cephalic fluid shift (movement of fluid towards the head).

The comparative analysis yielded compelling insights. While both spaceflight and the bed rest study induced some posterior shift of the brain, the astronauts’ brains exhibited a significantly more pronounced upward shift. This key difference strongly suggests that the unique conditions of actual spaceflight – beyond just fluid shifts – are responsible for the more comprehensive displacement observed in astronauts. The lack of gravitational pull in space allows the brain to float more freely within the skull, leading to movements that cannot be fully replicated in a simulated environment on Earth. This distinction is vital for understanding the true impact of microgravity and for developing effective countermeasures.

Duration: The Driving Factor Behind Brain Changes

One of the most striking correlations uncovered by the study was the direct relationship between the duration of space exposure and the extent of brain changes. The researchers observed that the brains of astronauts who spent longer periods in space shifted both up and backward “in a fashion that correlated with exposure duration.” This suggests a cumulative effect, where the longer an individual is in microgravity, the more pronounced these structural alterations become. This finding is particularly significant for future long-duration missions to distant destinations like Mars, which could involve crews spending years away from Earth.

Coauthor Rachael Seidler, a professor of physiology and kinesiology at the University of Florida, underscored this point in an interview with NBC News, stating, “The people who went for a year showed the largest changes.” While some alterations were even detectable in astronauts who undertook missions as short as two weeks, “duration seems to be the driving factor.” This indicates a spectrum of impact, with longer missions posing a greater challenge to brain stability and potentially recovery. Correspondingly, astronauts who spent extended periods in space, particularly those exceeding six months, reported greater difficulties regaining their balance and orientation upon returning to Earth, a clear functional manifestation of these underlying brain changes.

The magnitude of these shifts, while seemingly small in absolute terms, is highly significant within the delicate confines of the skull. Seidler elaborated on this, explaining, “It’s on the order of a couple of millimeters, which doesn’t sound like a big number, but when you’re talking about brain movement, it really is.” To put this into perspective, she added, “That kind of change is visible by eye.” This visual observability underscores that these are not microscopic or theoretical changes but rather macro-level physical shifts of the brain within its protective casing, prompting serious consideration for their physiological consequences.

Recovery, Remaining Questions, and Future Implications

Encouragingly, the study did observe a “widespread recovery… in all three dimensions over six months following spaceflight.” This indicates that the brain possesses a remarkable capacity for neuroplasticity and can, to a significant extent, revert to its pre-flight state. However, not all changes were fully reversible for every astronaut, with some deformations persisting beyond the six-month mark. This suggests that for certain individuals or after particularly long missions, some structural alterations might become more permanent, raising further questions about long-term neurological health.

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of the findings, as noted by Professor Seidler, was the general lack of severe symptoms reported by astronauts, such as debilitating headaches or overt cognitive impairment, either during or immediately after spaceflight. This observation presents a fascinating paradox: significant physical changes are occurring in the brain, yet the human system seems remarkably resilient in compensating for them, at least in the short term. This resilience, however, does not negate the need for deeper understanding, as subtle cognitive changes might be missed in current assessments, or long-term consequences might only manifest years later.

Indeed, many crucial questions remain unanswered. Researchers are still striving to understand precisely how spaceflight impacts specific individual brain regions, and whether certain areas are more vulnerable or more adaptable than others. Furthermore, the exact short- and long-term health consequences of these brain deformations and displacements, beyond temporary disorientation and balance issues, are largely unknown. Could they contribute to accelerated neurodegenerative processes, altered mood, or subtle cognitive deficits over time? The study’s authors also acknowledged the limitations of their sample sizes, which, while robust for astronaut research, mean that their findings may not be fully generalizable across all individuals, highlighting the need for more extensive studies.

In essence, humanity is only just beginning to comprehend the intricate ways in which microgravity remodels our most complex organ. This research is not merely academic; it is invaluable for charting a safe course as we prepare to venture even deeper into the cosmos. As Mark Rosenberg, an assistant professor of neurology at the Medical University of South Carolina, who was not involved in the study, aptly posed to NBC, “If you’ve been on Mars with one-third Earth’s gravity, or on the moon with one-sixth Earth’s gravity, will it take three or six times as long to get back to normal?” These questions underscore the monumental challenges and responsibilities that accompany our aspirations for interplanetary travel.

Rosenberg’s concluding remarks resonate deeply with the spirit of scientific exploration and human destiny: “Whether we care to admit it or not, we are eventually going to become a space-faring species. It’s only a matter of time. And these are just some of the unanswered questions that we need to sort out.” As we embark on this inevitable journey, understanding and mitigating the physiological impacts of space on the human brain will be paramount to ensuring the health, safety, and cognitive performance of the pioneers who will carry humanity’s dreams to the stars.

More on astronaut health: Something Is Malfunctioning With Astronauts’ Brains