A new, insidious botnet known as Kimwolf is rapidly expanding its reach, infecting over two million devices globally and posing a significant threat to the security of internal networks. This sophisticated malware exploits a critical vulnerability in residential proxy services, enabling it to tunnel through trusted connections and infiltrate devices hidden behind firewalls and routers. The implications are dire: everything you believed about your network’s security may now be dangerously outdated, leaving your local area network (LAN) vulnerable to a cascade of malicious activities.

The Kimwolf botnet’s explosive growth is attributed to its cunning propagation method. Instead of solely targeting individual devices directly, Kimwolf leverages residential proxy networks. These networks, sold to users seeking to anonymize or localize their internet traffic, inadvertently become conduits for the malware. Compromised devices within these proxy networks act as stepping stones, allowing Kimwolf to tunnel back into the local networks of the proxy endpoints. This means that even devices secured behind your home router and firewall are not safe, as the botnet can effectively bypass traditional security perimeters.

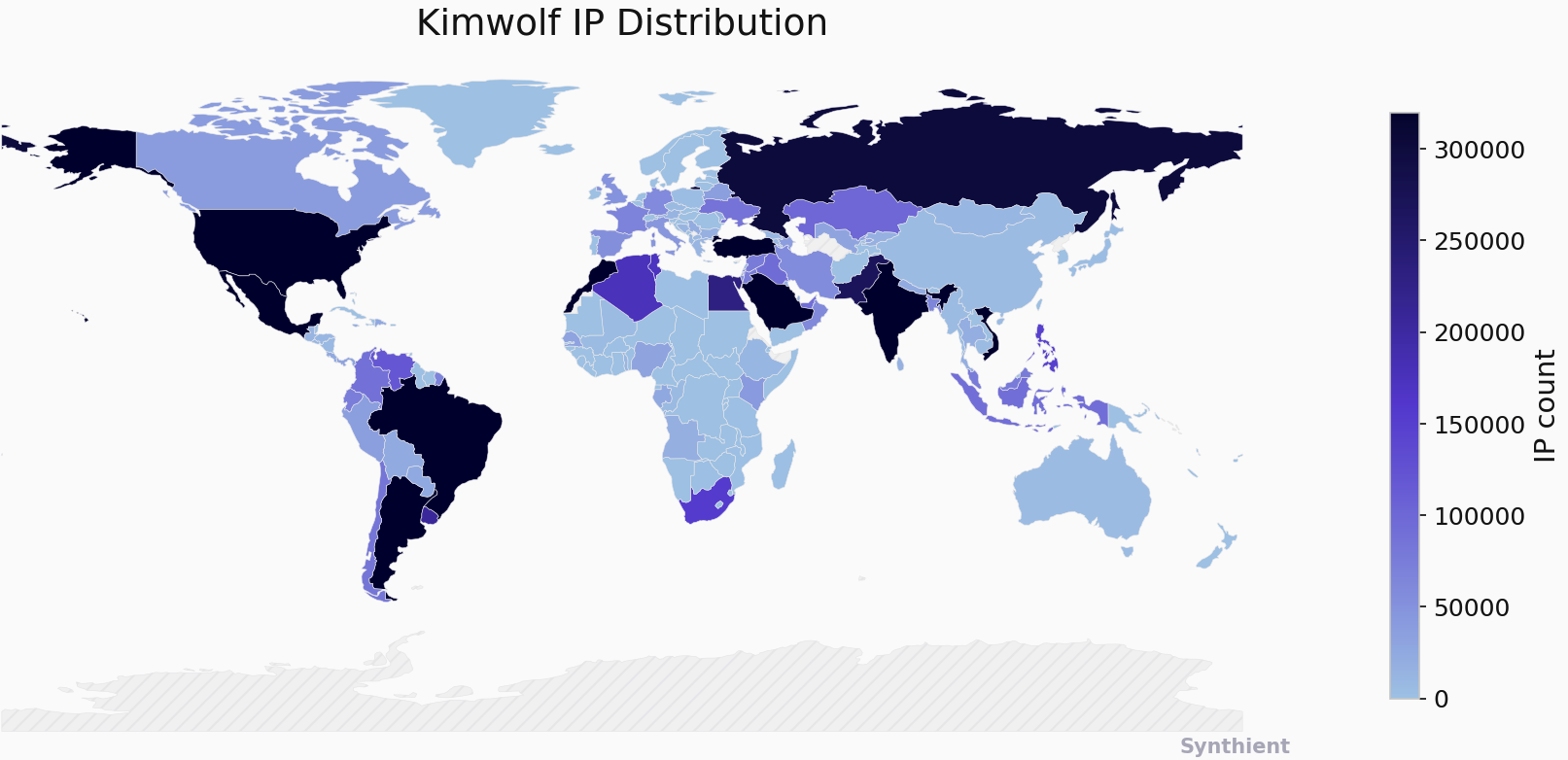

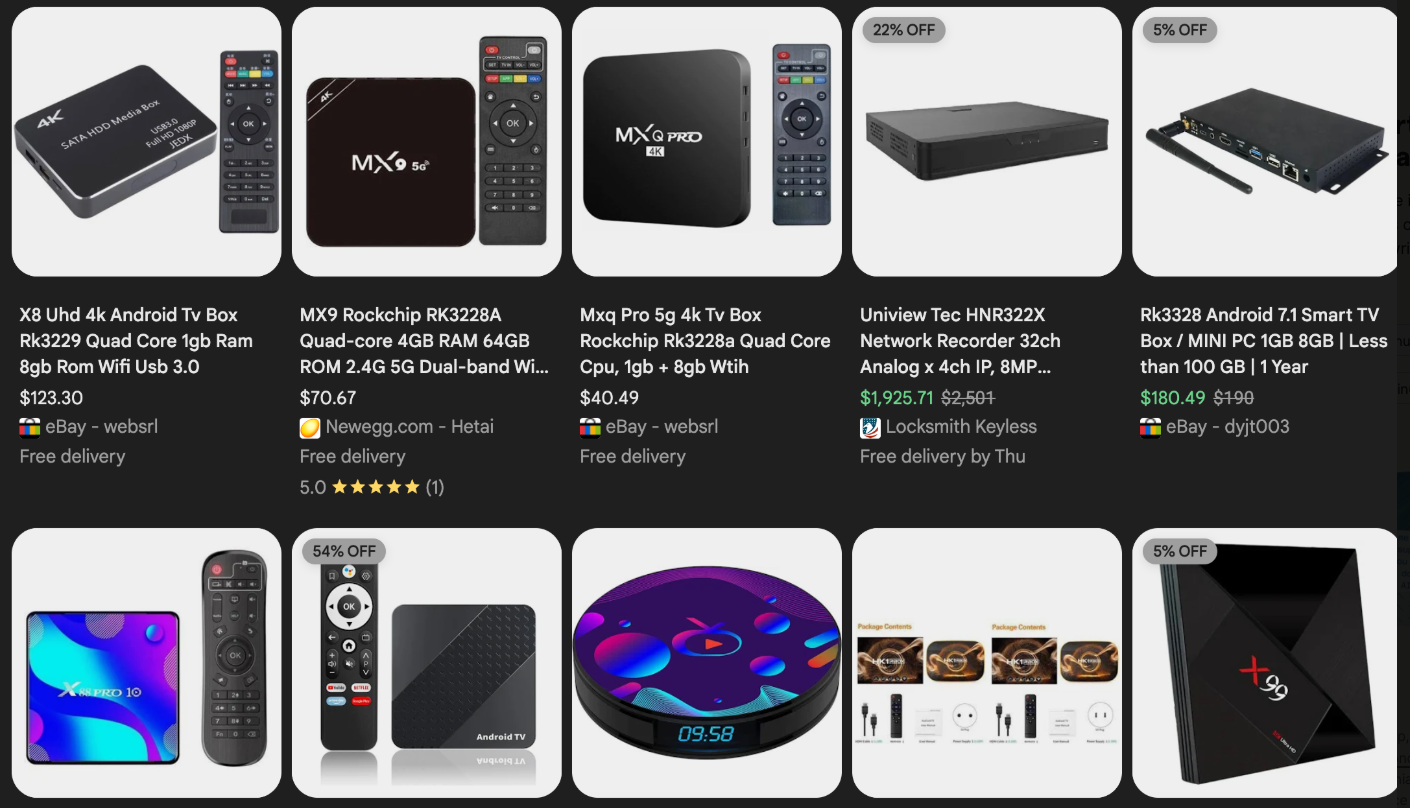

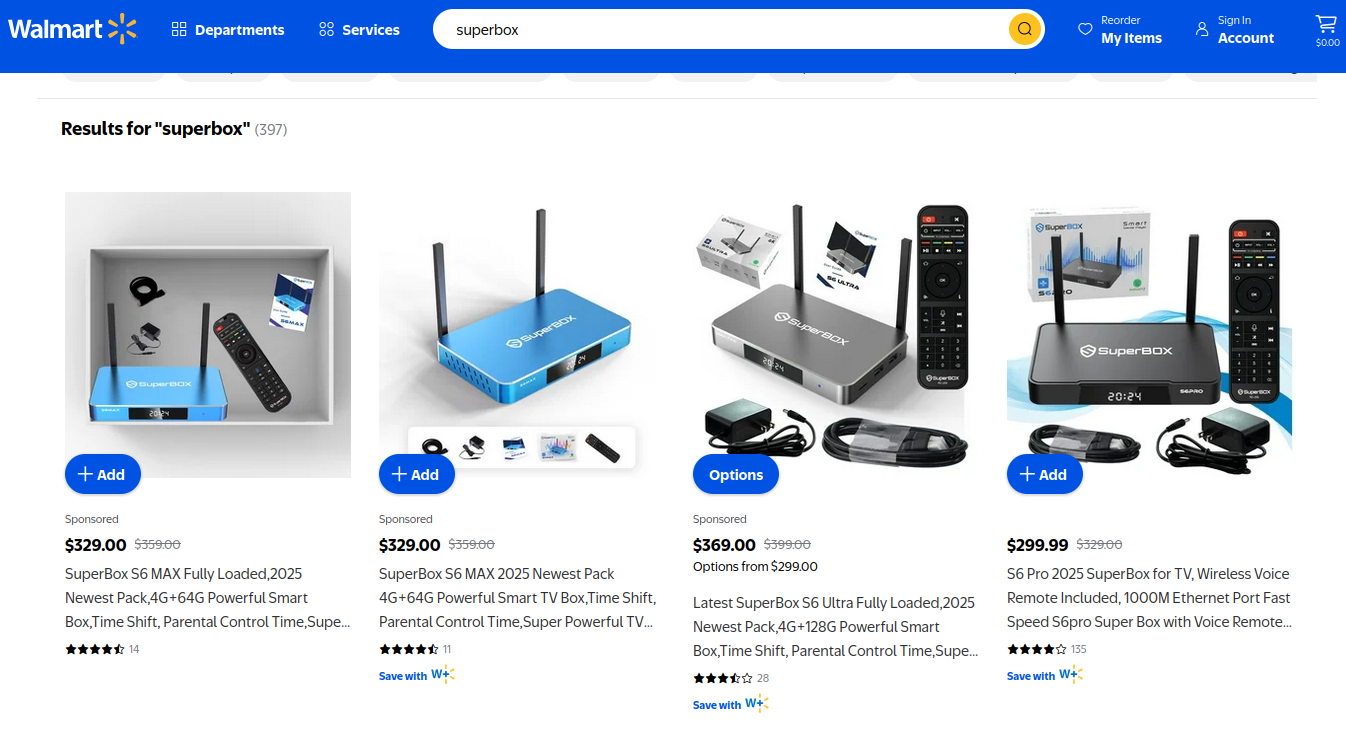

The primary vector for infection appears to be through unofficial Android TV boxes and digital photo frames commonly purchased from major e-commerce platforms like Amazon, BestBuy, Newegg, and Walmart. These devices, often marketed under no-name brands and priced between $40 and $400, are frequently advertised as a means to stream subscription video content for free. However, the hidden cost of this "free" access is the pre-installed malware or the requirement to download unofficial apps that turn the device into a residential proxy node. Security researchers have identified that a significant portion of these devices, particularly Android TV boxes, lack any built-in security or authentication, making them easy targets. Synthient, a security company, has observed that two-thirds of Kimwolf infections are on such Android TV boxes. The accompanying map from Synthient highlights concentrations of infected Kimwolf devices globally, with notable presences in Vietnam, Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States, indicating a widespread and urgent threat.

Further compounding the problem is the prevalence of Android Debug Bridge (ADB) mode being enabled by default on many of these unofficial Android TV boxes. ADB is a powerful diagnostic tool intended for manufacturing and testing, allowing remote configuration and firmware updates. However, when left enabled on consumer devices, it creates a security nightmare, as these devices constantly listen for and accept unauthenticated connection requests. This means that with a simple command, attackers can gain unrestricted "super user" administrative access to these devices.

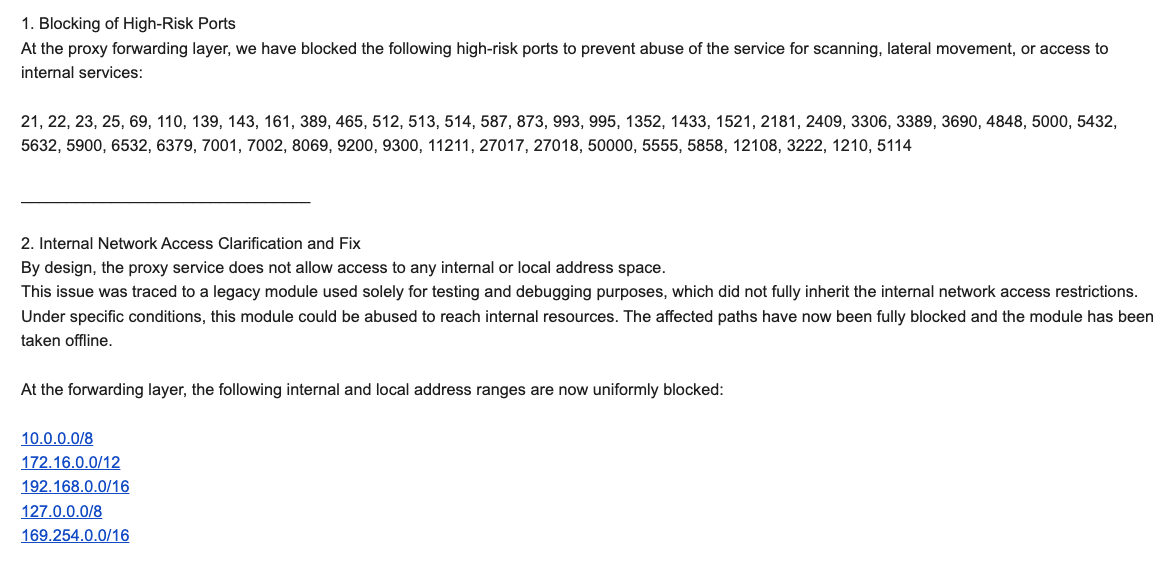

Benjamin Brundage, founder of Synthient, a startup specializing in detecting proxy network abuse, has been instrumental in uncovering the intricacies of the Kimwolf botnet. His research, conducted while he was an undergraduate computer science student at the Rochester Institute of Technology, suggests that Kimwolf is an Android-based variant of the Aisuru botnet. Brundage discovered that Kimwolf exploits a critical vulnerability in many large residential proxy services. The core weakness lies in these services’ insufficient measures to prevent customers from forwarding requests to internal servers of individual proxy endpoints. While most services attempt to block access to private IP address ranges (RFC-1918), Kimwolf operators found a way to circumvent these restrictions by manipulating Domain Name System (DNS) settings to point to these private ranges. This allows them to directly communicate with devices on the internal networks of proxy endpoints.

Brundage’s research revealed a strong correlation between new Kimwolf infections and proxy IP addresses offered for rent by China-based IPIDEA, currently the world’s largest residential proxy network. He observed that Kimwolf was rapidly expanding by exploiting IPIDEA’s proxy pool, with the botnet doubling in size within a week solely by tunneling through IPIDEA’s infrastructure. Synthient’s analysis indicated that over two-thirds of the devices within IPIDEA’s proxy pool were Android devices that could be compromised without any authentication. The attackers would leverage the compromised proxy endpoints to tunnel back and drop the Kimwolf malware payload.

In response to Brundage’s findings, IPIDEA’s security officer, Byron, stated that the vulnerability was traced to a legacy module used for testing and debugging, which had not fully inherited internal network access restrictions. IPIDEA claims to have since patched these vulnerabilities, blocked access to internal resources, and implemented mitigations to prevent abuse. However, Riley Kilmer, founder of Spur.us, a firm that tests and filters proxy traffic, confirmed that IPIDEA and its affiliates allowed full and unfiltered access to the local LAN. Kilmer also highlighted that certain popular unsanctioned Android TV boxes, like the Superbox, leave ADB running on localhost, further facilitating malicious exploitation when connected to a proxy service like IPIDEA.

The history of such vulnerabilities is not new. Both Brundage and Kilmer suggest that IPIDEA may be a reincarnation of the notorious 911S5 Proxy service, which operated from 2014 to 2022 and was known for its extensive reach into internal corporate networks. The U.S. Department of the Treasury later sanctioned the alleged creators of 911S5. This pattern of evasion and reappearance highlights the persistent nature of these threats.

The practical implications of the Kimwolf botnet are significant. A seemingly innocuous act, like allowing a guest to use your Wi-Fi, can lead to infection if their device is compromised. The botnet can then tunnel into your local network, scan for vulnerable devices with ADB enabled, and infect them, turning your home network into a launchpad for further malicious activities. Attackers could even manipulate your router’s DNS settings, redirecting your web traffic to malicious servers, reminiscent of the 2012 DNSChanger malware.

The Chinese security firm XLab was among the first to chronicle the rise of the Aisuru botnet and subsequently Kimwolf. Their analysis indicated that Kimwolf has infected between 1.8 and 2 million devices, with a strong focus on TV boxes in residential environments. XLab also noted the botnet’s author’s "obsessive" fixation on KrebsOnSecurity, embedding "easter eggs" related to the author’s name within the botnet’s code and communications.

For average users, detecting Kimwolf infections or other residential proxy malware on their network is challenging due to a lack of accessible tools and expertise. Synthient has provided a webpage where users can check if their public IP address has been associated with Kimwolf infections, and a list of vulnerable unofficial Android TV boxes is also available. Experts strongly advise consumers to be wary of these devices, to avoid them altogether, and to prioritize well-known brands for any internet-connected purchases. Chad Seaman, a principal security researcher at Akamai Technologies, emphasizes that the notion of a secure LAN is outdated and that consumers should be paranoid about sketchy devices and residential proxy schemes.

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that many of these insecure devices are widely available and heavily marketed, often for illicit purposes. The entertainment industry has faced criticism for not exerting more pressure on e-commerce vendors to cease selling such actively malicious hardware. Ultimately, the Kimwolf botnet serves as a stark reminder that the security of our local networks is under constant threat, and vigilance, coupled with informed purchasing decisions, is paramount.