For over two decades, millions of ordinary people across the globe contributed their personal computer’s idle processing power to an extraordinary quest: the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. This pioneering citizen science project, known as SETI@home, harnessed the collective might of a distributed computing network to scrutinize vast amounts of cosmic data, yielding an astonishing 12 billion detections and ultimately narrowing down the possibilities to 100 intriguing signals that warrant a deeper look. While the project officially concluded in 2020, its legacy continues to shape the future of SETI research, demonstrating the power of crowdsourced science and laying the groundwork for more sophisticated alien-hunting endeavors.

The Genesis of a Cosmic Search Party

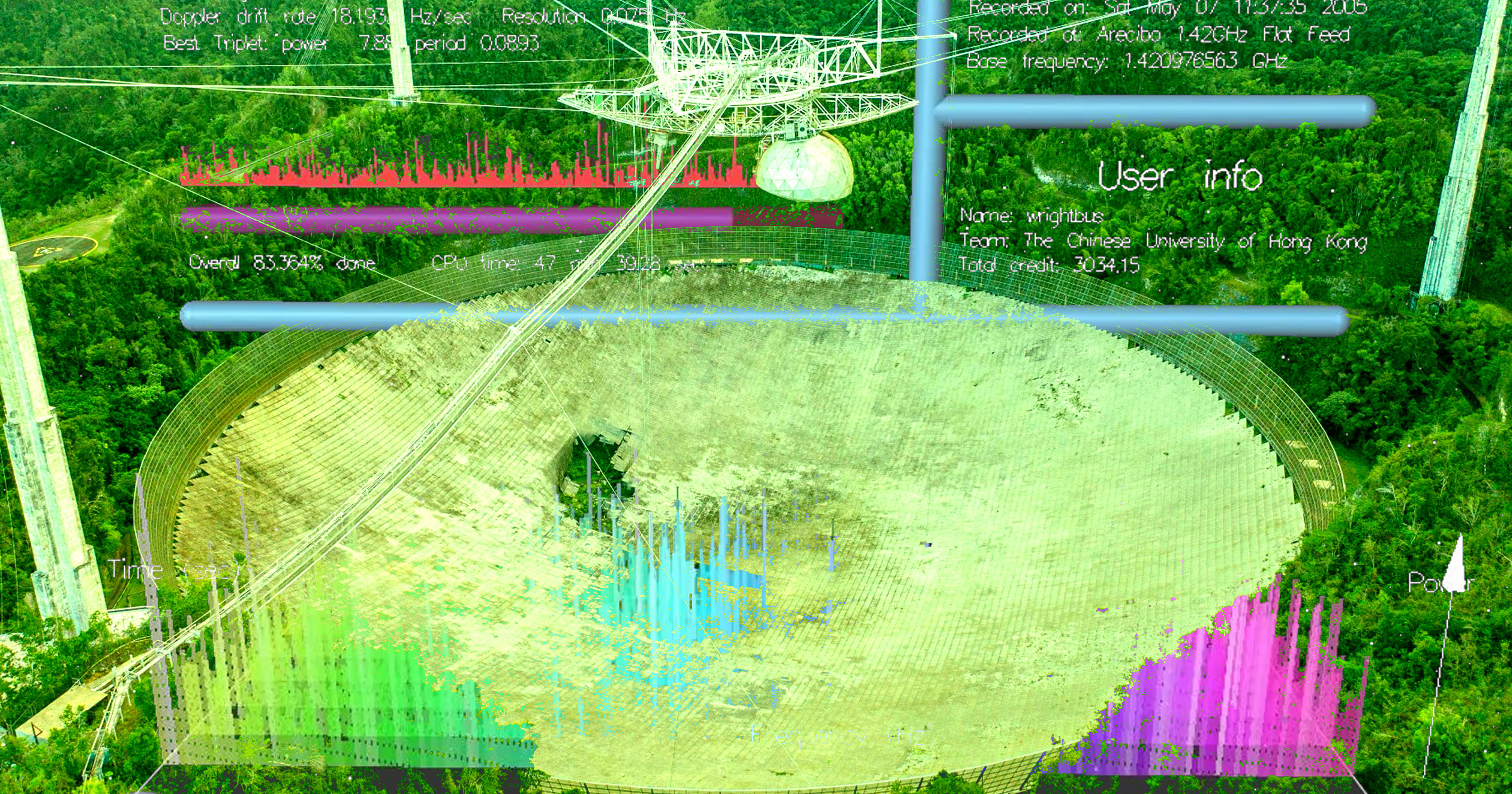

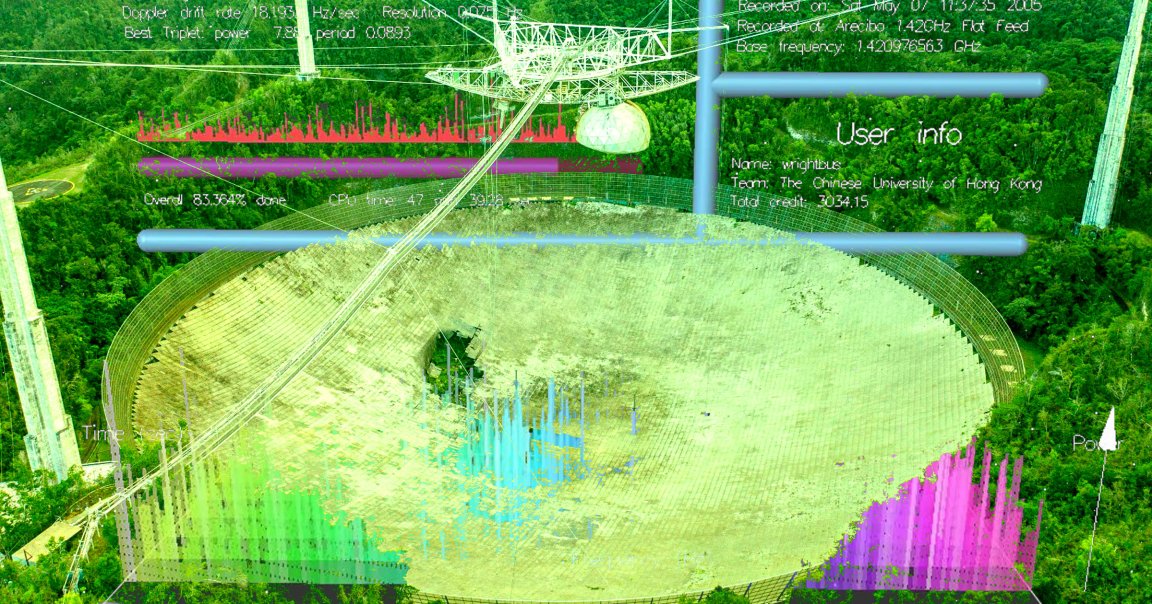

The human fascination with life beyond Earth is as old as civilization itself, but the scientific pursuit of extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI, truly began with the advent of radio astronomy. In 1999, UC Berkeley launched SETI@home, a revolutionary initiative that democratized the search. Instead of relying on a handful of supercomputers, the project leveraged the burgeoning internet and the widespread ownership of personal computers. Volunteers downloaded a screensaver-like program that would automatically process small chunks of data collected by the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico whenever their computer was idle. This concept of “distributed computing” was groundbreaking, allowing scientists to access computational power on an unprecedented scale, far exceeding what any single institution could afford.

The underlying premise was simple yet profound: if an intelligent civilization were trying to communicate across the cosmos, or if their technology emitted detectable radio waves, a powerful radio telescope could pick up these signals. The challenge, however, was sifting through the immense background noise and natural astrophysical phenomena to identify any artificial, non-random patterns. SETI@home provided the human-powered computational grid needed for this colossal task, turning millions of home PCs into a global supercomputer dedicated to scanning the universe for whispers from alien worlds.

A Global Effort: 21 Years of Stargazing from Home

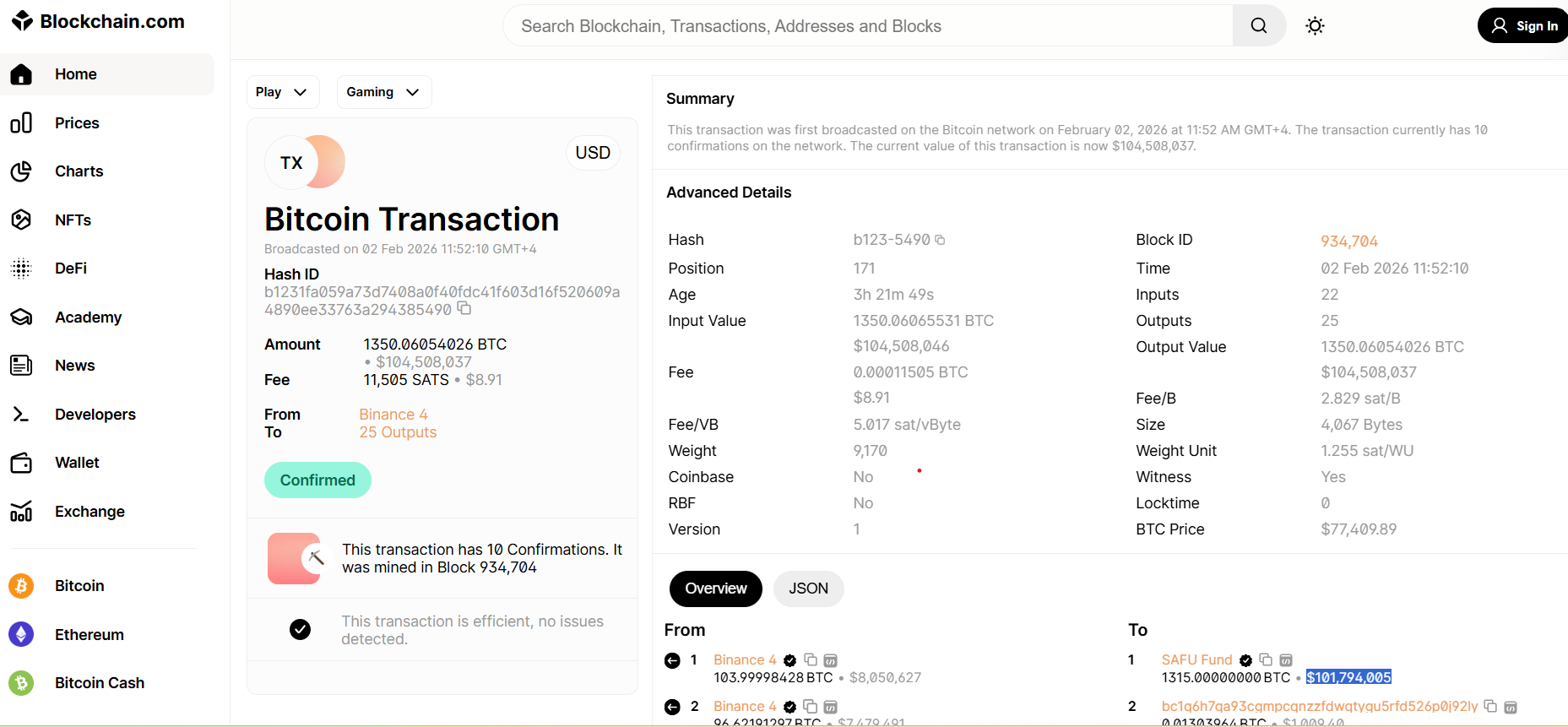

Over its 21-year lifespan, SETI@home became one of the most popular crowd-sourced research projects ever, attracting millions of participants from nearly every country. These volunteers, driven by curiosity and the hope of making a historic discovery, collectively contributed billions of hours of CPU time. The sheer volume of data processed was staggering, amounting to what UC Berkeley described as 12 billion “detections” – instances where the software identified something that might be an anomalous radio signal. Each detection was a potential needle in a cosmic haystack, requiring meticulous analysis to determine its origin.

The initial filtering process was complex, designed to eliminate obvious terrestrial interference and known astronomical sources. This first pass helped reduce the vast ocean of data to a more manageable pool. Yet, even after initial automated filtering, the remaining candidate signals still numbered in the millions. The project then employed more advanced algorithms and, eventually, specialized supercomputers to further refine the data, searching for persistent, narrow-band signals that would be indicative of an artificial origin, as opposed to the broadband noise produced by natural cosmic phenomena. This painstaking process slowly but surely whittled down the colossal dataset.

Honing In: The 100 Signals of Interest

The rigorous analysis, spanning years, eventually led researchers to identify approximately 100 signals that were deemed “worth a second look.” These signals stood out from the noise, exhibiting characteristics that couldn’t be easily dismissed as terrestrial interference or natural astrophysical events. They were not definitive proof of alien life, but rather tantalizing candidates that merited further investigation with more powerful and precise instruments. The journey from 12 billion detections to a mere 100 highlights the incredible challenge of SETI, where the vastness of space and the omnipresence of noise make even potential discoveries incredibly rare.

Since July 2025, scientists have embarked on the crucial follow-up phase, utilizing China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) – currently the world’s largest single-dish radio telescope – to re-observe the sky locations corresponding to these 100 identified targets. The hope is that by pointing FAST’s incredibly sensitive dish at these specific coordinates, they might catch another glimpse of these anomalous signals, thereby confirming their extraterrestrial origin and paving the way for further study. This collaboration with FAST represents a new chapter for the SETI@home legacy, demonstrating the global nature of scientific inquiry.

The Arecibo Legacy and Its Tragic End

Integral to the SETI@home project was the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, a monumental feat of engineering that, for decades, held the title of the world’s largest single-aperture radio telescope. Its massive 1,000-foot (305-meter) dish, nestled in a natural karst depression, was an icon of scientific exploration, contributing not only to SETI but also to planetary radar astronomy, atmospheric science, and pulsar research. Arecibo’s data formed the very foundation of SETI@home’s massive dataset, making it a pivotal instrument in humanity’s quest for cosmic companionship.

Tragically, Arecibo’s illustrious career came to an abrupt and devastating end in 2020. After suffering significant structural damage due to cable failures, the telescope platform ultimately collapsed during a storm. The loss of Arecibo was a severe blow to the scientific community worldwide, particularly for SETI researchers who had relied on its unparalleled sensitivity for so long. Its decommissioning marked the end of an era, but the data it collected continues to be a treasure trove, still yielding insights years after its operational demise.

Beyond Detection: Scientific Contributions and Lessons Learned

Even without a definitive “first contact” announcement, SETI@home was far from a waste of time. The project has already yielded significant scientific contributions, evidenced by two papers published last year in The Astronomical Journal. These publications aren’t just about the hunt for aliens; they delve into the methodology, the challenges, and the broader implications for future SETI endeavors. As project cofounder David Anderson eloquently put it, “If we don’t find ET, what we can say is that we established a new sensitivity level. If there were a signal above a certain power, we would have found it.” This statement underscores a crucial scientific outcome: even a null result helps refine the search parameters, narrowing down the possibilities and informing future strategies.

The project also served as a monumental case study in distributed computing itself, providing invaluable insights into managing massive datasets, coordinating millions of volunteers, and optimizing data processing algorithms. It pioneered a model of citizen science that has since been replicated in various other scientific fields, from medical research to climate modeling, proving that the collective power of individuals can drive scientific discovery.

The Persistent Challenge of Radio Frequency Interference (RFI)

One of the most significant lessons learned, and a persistent hurdle for SETI, is the pervasive nature of radio frequency interference (RFI). As astronomer and project director Eric Korpela highlighted, “We have to do a better job of measuring what we’re excluding. Are we throwing out the baby with the bath water? I don’t think we know for most SETI searches, and that is really a lesson for SETI searches everywhere.” RFI emanates from countless terrestrial sources: cell phones, television broadcasts, satellite communications, Wi-Fi networks, and even seemingly innocuous devices like microwave ovens. Distinguishing a genuine extraterrestrial signal from the cacophony of human-made noise is an immense challenge. Researchers must develop increasingly sophisticated filters and algorithms to identify and remove RFI without inadvertently discarding a faint, genuine signal.

The concern is that an actual alien signal, if it exists, could be weak, intermittent, or buried within a band already saturated by human transmissions. Future SETI projects will need to incorporate more robust RFI mitigation strategies, including better baseline measurements of local interference, more adaptive filtering techniques, and perhaps even leveraging artificial intelligence to differentiate subtle patterns that might escape conventional detection methods.

Disappointment and Renewed Hope

After two decades of dedicated searching across “billions and billions” of stars in the Milky Way, the lack of a definitive smoking gun left some of the alien-hunting organizers understandably deflated. “We are, without doubt, the most sensitive narrow-band search of large portions of the sky, so we had the best chance of finding something,” Korpela reflected. “So yeah, there’s a little disappointment that we didn’t see anything.” This sentiment captures the bittersweet reality of SETI: immense effort and hope, often met with silence.

However, Korpela and the team haven’t given up. The experience has merely sharpened their focus and informed their approach for future endeavors. Korpela remains optimistic about the potential for future crowdsourced projects, particularly given the immense advancements in computer power and improved internet connections since SETI@home began. “I think that you could still get significantly more processing power than we used for SETI@home and process more data because of a wider internet bandwidth,” he mused. The primary constraint, however, remains funding for the personnel required to manage such complex, large-scale scientific initiatives, indicating that while technology progresses, human resources and financial backing are still critical.

The Enduring Mystery and Future Horizons

The SETI@home project concluded with many “what-ifs” still lingering. “There’s still the potential that ET is in that data and we missed it just by a hair,” Korpela pondered. This uncertainty is inherent in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. The cosmos is vast, our search methods are still evolving, and the nature of potential alien signals is entirely speculative. We might be looking for the wrong kind of signal, in the wrong place, or at the wrong time. The universe operates on scales that dwarf human comprehension, making the search for a needle in a cosmic haystack an understatement.

Despite the challenges and the lack of confirmed contact, the legacy of SETI@home is profound. It galvanized a global community around a shared scientific dream, pushed the boundaries of distributed computing, and provided invaluable data and lessons for the next generation of SETI researchers. As humanity continues to gaze at the stars, armed with ever more sensitive telescopes and sophisticated analytical tools, the spirit of SETI@home—a collective endeavor driven by curiosity and hope—will undoubtedly continue to inspire the quest to answer one of humanity’s oldest and most profound questions: Are we alone?

More on radio signals: Scientists Intrigued by Radio Signals Coming From Comet